Two Black Holes Smashed and Completely Changed What We Know About the Universe

Researchers have spotted the most powerful black hole merger ever recorded and unearthed evidence of a previously disputed class of black hole: intermediate-mass black holes.

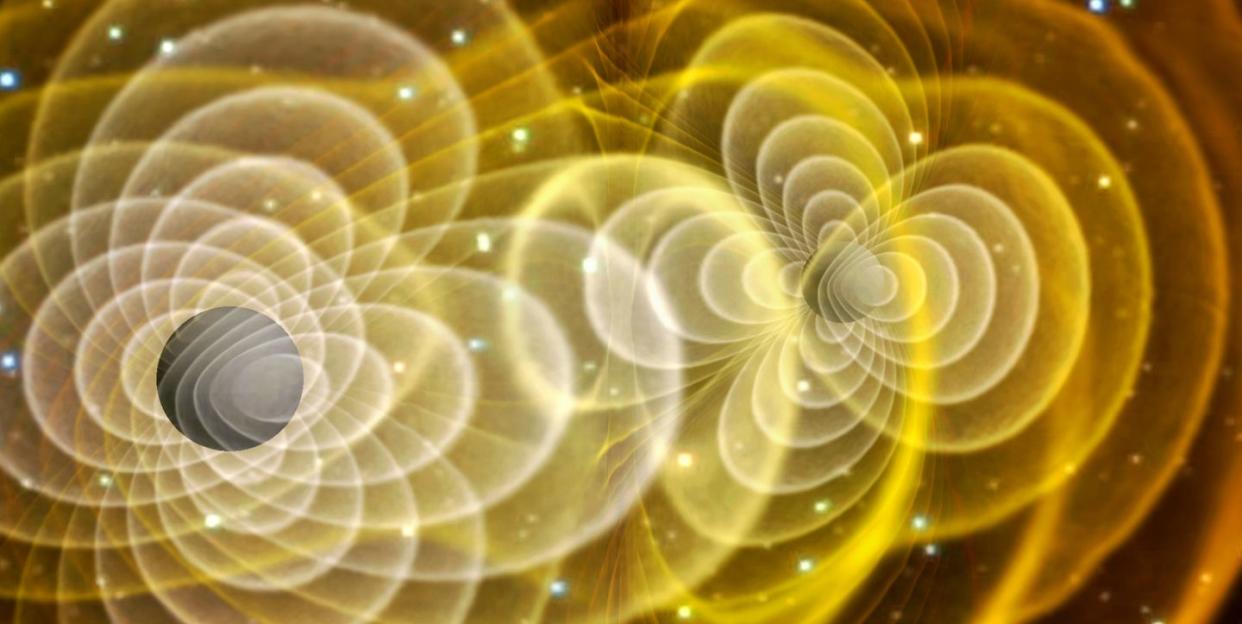

The astronomers used the LIGO and Virgo observatories to analyze the gravitational waves.

The perplexing collision could be the result of a chain reaction of collisions, researchers say.

Roughly seven billion years ago, two monstrous black holes slammed together in a catastrophic celestial event so intense, it shot a pulse of gravitational waves out across the universe. Astonishingly, those gravitational waves only reached Earth one year ago, and astronomers now believe they've spotted the most powerful black hole collision yet: an event they've dubbed GW190521.

🌌 You love our badass universe. So do we. Let's explore it together.

Researchers at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the U.S. and the Virgo Observatory in Italy first detected the waves—ripples in the fabric of space-time—in May 2019. The two smashed black holes at the heart of the collision were 66 and 85 times more massive than our sun, astronomers report in two papers published last week in Physical Review Letters and The Astrophysical Journal. When they collided, they formed a gargantuan black hole approximately 142 times more massive than our sun.

Not only is this likely the most powerful explosion ever recorded, but it proves the existence of a rare class of black holes: intermediate-mass black holes. “Now we can settle the case and say that intermediate-mass black holes exist,” LIGO astrophysicist Christopher Berry of Northwestern University, told National Geographic.

A black hole 85 times the mass of our sun theoretically shouldn't exist. It doesn't pair well with the theories researchers have about how stars die. Stars that range from a few times to 60 times the mass of our sun typically burn all of their fuel and eventually collapse in on themselves, forming a "conventional" black hole.

Stars that are about 60 to 130 times more massive than our sun go out with a bang, but they usually don't become black holes. Instead, they form something called a pair-instability supernova. The heat that occurs during the star's compression is so powerful, all of the material ejected is destroyed. According to the current theory, it simply can't become a black hole. (Supermassive black holes, like the one photographed at the center of M87, form from stars millions to billions the mass of our sun.)

“A discovery like this is simultaneously disheartening and exhilarating," LIGO team member Daniel Holz, a theorist at the University of Chicago, told the New York Times. "On the one hand, one of our cherished beliefs has been proven wrong. On the other hand, here’s something new and unexpected, and now the race is on to try to figure out what is going on."

So how did this massive collision unfold? Some researchers propose the black holes that slammed into each other were primordial, meaning they've been around since shortly after the Big Bang and follow their own set of cosmic guidelines. Another theory suggests perhaps these mysterious intermediate-mass black holes formed from black hole mergers that occurred earlier.

In order for this scenario to work, location is key. When black holes collide, the gravitational waves they generate often cause them to recoil, propelling them out of their galaxy. But for these two massive black holes to meet, the galaxy in which their previous collisions occurred would have to have been incredibly crowded and had enough of a gravitation pull to keep the black holes relatively close together.

Astronomers aren't sure where the massive collision occurred. There is, however, a clue. In June, researchers at the Zwicky Transient Observatory in California spotted the flare of a quasar in roughly the same patch of sky. This bright flash could be the result of a shockwave produced by the recoiled black hole formed during the GW190521 event. But more work needs to be done to link the two phenomena.

In any case, this is a watershed moment in astrophysics. Discoveries made at the Virgo Observatory and LIGO, the twin observatories located in Washington and Louisiana, respectively, have reshaped our understanding of the universe and earned researchers there a Nobel Prize. The work done at these observatories has allowed astronomers to slowly tease out our universe's most cryptic secrets. They're not finished yet.

Explore the Cosmos With These Telescopes

You Might Also Like