South Carolina Inmate’s Electric Chair Execution Is Halted—Until a Firing Squad Is Available

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

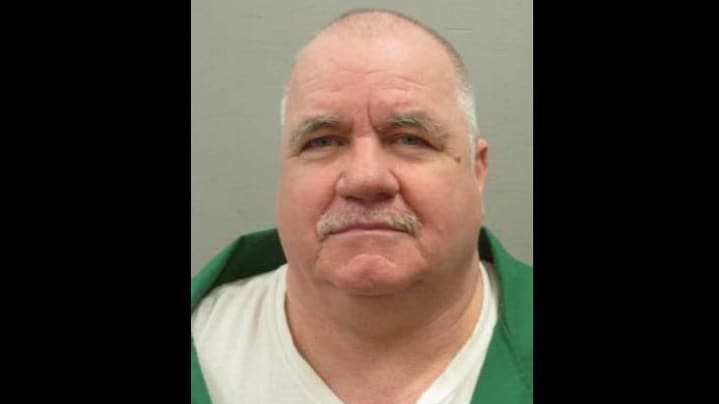

Two days before South Carolina death row inmate Brad Sigmon was due to be put to death in the state’s 109-year-old electric chair, he won a rare reprieve from the state’s Supreme Court.

Fellow prisoner Freddie Owens, who was set to be put to death a week later, was also spared at least temporarily as the court ruled Wednesday that the electrocution deaths would violate the “statutory right of inmates to elect the manner of their execution.”

But just as quickly as the court handed down the ruling vacating the upcoming executions until another method can be offered, the South Carolina Department of Corrections vowed to waste no time in “moving ahead” with a firing squad.

“We will notify the court when a firing squad becomes an option for executions,” the department said in a statement.

The dizzying news came after 63-year-old Sigmon was said to be “terrified” ahead of an execution scheduled for Friday that he fought desperately to stop, according to Alli Sullivan of the nonprofit Death Penalty Action.

Sullivan said she had been corresponding with Sigmon on a daily basis until last weekend, when she grew “super concerned” after he stopped reaching out. In the last phone conversation the two had, Sigmon appeared to break down after revealing that he “doesn’t know if [he] can get the horror out of [his] mind of being fried to death,” Sullivan wrote in an update on the case posted to Facebook.

The electric chair was the only method offered to Sigmon in accordance with the state’s new capital punishment law, which effectively made it the default manner of execution. While the law, passed in May, also provided for death by firing squad, the state Department of Corrections acknowledged that it would not be logistically possible to use one in time for Sigmon’s planned June 18 execution.

The state has said it has been unable to obtain lethal injection drugs after the last batch expired in 2013, and manufacturers have since stopped selling the drugs in cases where they know they will be used in executions.

It is not clear how long the department will take to assemble a firing squad now, and authorities have not provided a timeline. Sigmon’s lawyer, Megan Barnes, could not immediately be reached for comment.

The state Supreme Court’s stay on Wednesday came after a federal judge last week seemed to quash any hope of a reprieve by rejecting Sigmon and Owens’ arguments that the electric chair would violate the Eighth Amendment by being unnecessarily painful.

Many experts have said there appeared to be political pressure in the South Carolina legislature’s passage of the new law. Sullivan said she was struck by the fact that Sigmon was given a date for his execution “almost immediately” after the passage of that law, which Gov. Henry McMaster praised as a way to move forward with executions after a 10-year pause.

According to Robert Dunham, executive director of of the Death Penalty Information Center and a widely renowned expert on capital punishment, South Carolina’s shift to more “primitive” methods of executions stemmed from a “frustration over its inability to obtain drugs to be used in executions.”

McMaster had made his push for alternative methods of execution clear, Dunham said, when in 2017 he staged a press conference “right outside of the prison where the executions would occur” claiming authorities were unable to carry out an execution because there were no execution drugs for lethal injections.

“This was a deliberate political ploy by Gov. McMaster to create the appearance of an execution drug emergency in order to try to coerce the legislature into allowing executions by electric chair.”

“As best I can tell, the only reason for it was a desire to carry out executions,” Dunham said.

While support for capital punishment nationwide is at a 50-year low, Dunham said, there are a handful of states that are getting “more desperate” to carry out executions despite the lack of lethal injection drugs, and are thus “retreating to more primitive means” of execution.

South Carolina’s shift to the electric chair is part of a wider trend, Dunham said.

“They piggybacked on what other states that wanted to carry out executions were doing,” he said, though other states offered backup methods.

“Arizona has just authorized the use of the same gas that the Nazis used to kill people in the concentration camps. Utah passed a law re-authorizing the use of the firing squad as an alternative, should lethal injection drugs be unavailable, or declared unconstitutional... In Tennessee, the electric chair is the backup, but not the default. So South Carolina had the most extreme statute in that it chose as a default method, a method that was known to be excruciatingly painful.”

“But for the most part, what these states are doing now is laying bare the reality of capital punishment. With the lethal injections, you had the false appearance of civility, of a peaceful, medical-ish proceeding that put a prisoner to sleep... But if you electrocute somebody, or if you execute them with Holocaust gas, or you fire four bullets into their heart, you can’t deny the brutality of the punishment,” Dunham explained.

While the state Supreme Court’s ruling on Wednesday was met with sighs of relief by many who have been alarmed by Sigmon’s case, the Department of Corrections is still plowing ahead with plans for another scheduled execution date, albeit by other means.

Even before his stay, Sigmon had expressed dread about the prospect of being granted a reprieve only to face the same countdown to death a few months later. In a Facebook post about the case, Sullivan recalled him confiding, “I don’t know if I could go through all of this again.”

Sigmon was sentenced to death for bludgeoning his ex girlfriend’s parents to death with a baseball bat in 2001.

Mike Zoosman, a former federal prison chaplain and the founder of the group L’chaim - Jews Against the Death Penalty who also has corresponded with Sigmon, said Sigmon has “absolutely” been remorseful about his crime and “is no longer the person he was when he committed that horrific act.”

“Unlike some people who will deny their part and their culpability, he, from day one, from the first conversation we had, he said that what he did was awful and he’s not making excuses for it,” Zoosman said. “And he would want to spend the rest of his life in prison for that, but he does not want to die.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.