California is suddenly snow-capped and very wet. But how long will the water rush last?

The dusty hills of Griffith Park are sprouting shades of green. In Pasadena, water is streaming through arroyos that only weeks ago sat caked and dry. And from the perfect vantage point downtown, the distant San Gabriel Mountains are gleaming with crowns of snow.

After one of the driest years in recent memory, Los Angeles — and California — is off to a notably wet start. The state received more precipitation in the final three months of 2021 than in the previous 12 months, the National Weather Service said.

Statewide, 33.9 trillion gallons of water have fallen since the start of the water year, which runs from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30 to accommodate for the wet winter months and the springtime runoff. That three-month tally has already surpassed the previous water year's 12-month total of 33.6 trillion gallons. By comparison, Lake Tahoe holds about 40 trillion gallons.

“It’s been a great start to the water year,” said Cory Mueller, a meteorologist with the weather service in Sacramento. “Most areas have already seen what they saw last water year and then some, just in the three months we’ve had.”

But while all that moisture gave a much-needed boost to statewide drought conditions, Mueller and other experts emphasized that California will need to maintain this wet trend in order to truly climb out of its dry spell. The 2021 water year was California's driest in a century, and more than half of the state's water years since 2000 have been dry or drought years.

“Not getting paid for three months and then getting a normal paycheck doesn’t put you back to normal in your bank account,” said Noah Diffenbaugh, a climate scientist at Stanford University.

The same is true for California’s drought.

“Those [precipitation] deficits have been so pronounced through so much of the state that it will take more than one normal year to overcome, and we don’t know how this year will ultimately play out,” Diffenbaugh said. “That said, it’s a very encouraging start.”

There have, indeed, been some promising improvements.

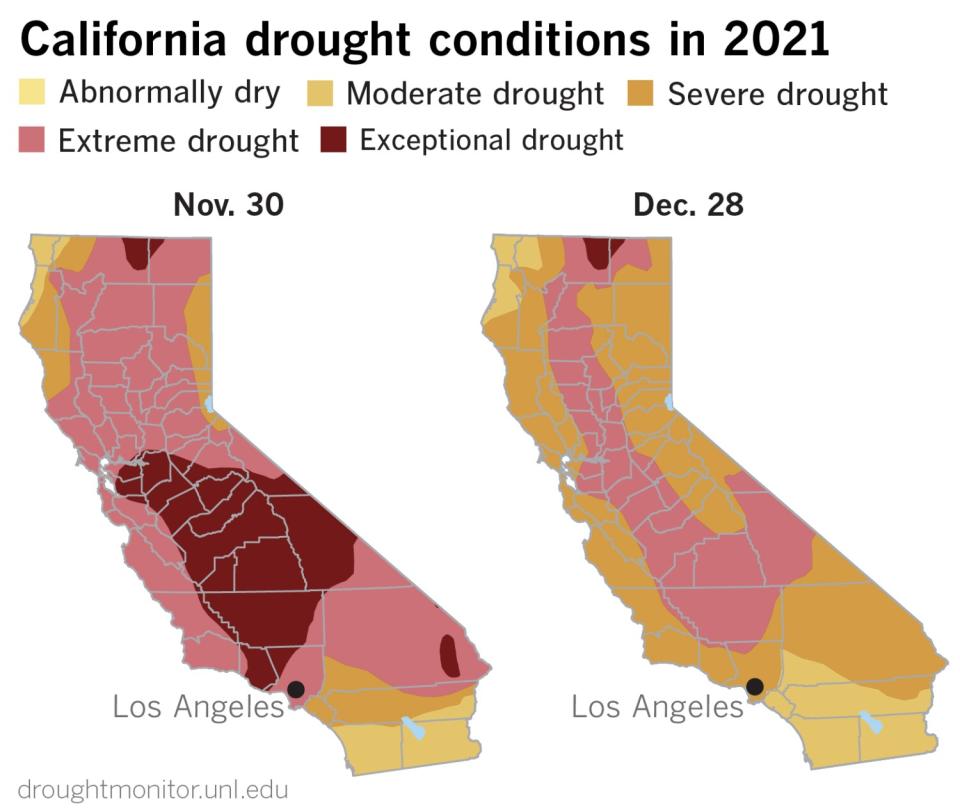

The U.S. Drought Monitor map — which has long indicated severe, extreme or exceptional drought conditions in most of California — looked slightly less worrisome after the early storms.

From Nov. 30 to Dec. 28, large swaths of the state — including Los Angeles and much of the Sierra Nevada — saw at least one level of improvement, according to a Times analysis. Almost no areas remain in the "exceptional drought" category.

The recent rains "did not completely eliminate the drought," said Brad Pugh, a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who helps manage the Drought Monitor map. "There's still long-term precipitation deficits dating back two years. But it certainly helped improve drought conditions."

Much of the state is still in the "extreme" drought category.

But Pugh said some seasonal forecasts are shifting in a positive direction. In October, NOAA's outlook favored a drier-than-normal winter, a prediction that did not come to pass in December.

The agency's latest three-month precipitation outlook now shows "equal chances of below, near or above normal precipitation" in much of Northern California this season, Pugh said, adding, "It's a slightly wetter outlook."

Even a slightly wetter outlook comes as welcome change for the parched state. In 2021, record-breaking heat and dryness contributed to a devastating wildfire season that saw more than 2.5 million acres burned and thousands of homes destroyed.

Conditions were so grim that state officials had to truck young salmon from the Central Valley to the Pacific Ocean because of low river levels. Later, regulators were forced to shut down a major hydroelectric power plant at Lake Oroville for the first time because of low water levels.

And Lake Mead — long considered a lifeline for water in the West — dwindled to historic lows, leaving a stark "bathtub ring" around its perimeter as evidence of just how bad things had become.

The recent storms gave the region's reservoirs a lift, but most are still lacking, said Bill Patzert, a retired climatologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"Reservoirs, especially Lakes Mead and Powell, are very depleted, groundwater and aquifers have been dangerously drawn down and, in SoCal, most of this lovely rain ended up in the Pacific," Patzert said.

Lake Mead on Tuesday was at about 34% of its capacity, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Lake Oroville was about 39%.

In a year-end update, officials at the California Department of Water Resources said December's storms offered a "glimmer of hope," but that more would be needed "before we can be in a place where drought conditions are no longer of concern."

The 2020-21 water years combined rank as the two driest years in California's statewide precipitation record, surpassing even the historic dry years of 1976-77, the agency said.

"Even if we get soaked and snowed in the next three months, the impacts of two decades of on-again, off-again — mostly on-again — rain and snow deficits will not be erased," Patzert said.

Notably, much of the precipitation since Oct. 1 has fallen as snow, which is extremely valuable as both a water source and a water storage system in the state. Snowpack that melts in the warm spring and summer months tends to provide an extra burst of water at a moment when precipitation stops and demand begins to peak.

Yosemite National Park saw its snowiest December in more than 40 years of record keeping, park officials said. The snowfall gauge at Tuolumne Meadows recorded 154 inches of new snow through Dec. 29, surpassing the previous record of 143 inches set in 1996.

The UC Berkeley Central Sierra Snow Lab at Donner Pass also recorded its snowiest December on record with 214 inches, or more than 17 feet, officials said.

The piles of powder also broke the lab's 51-year October-through-December snowfall record of 260 inches set in 1970, with 268 inches falling during that three-month stretch this year.

"Not bad for having a very dry November and early December," station manager Andrew Schwartz said.

The Water Year (WY) is off to a great start!

Digging into the state data🤓

Current WY volume ~33.9 trillion gallons

Last WY ~33.6 trillion gallons

This means that the state has received more precip than last year. For comparison Lake Tahoe contains ~40 trillion gallons. #CAwx pic.twitter.com/T5hbojjJci— NWS Sacramento (@NWSSacramento) January 1, 2022

Based on records dating to 1895, November 2021 was the seventh-warmest and eighth-driest November on record in the U.S., with 46 of the contiguous 48 states seeing below-average precipitation, according to NOAA. California, particularly Southern California, along with the rest of the Southwest, stood out among the rain-deprived regions of the country.

But by the end of December, moisture was markedly improved. Officials conducted the first snow survey of the season at Phillips Station near South Lake Tahoe and found that the month's storms brought the state’s mountain snowpack to about 160% of average for this time of year.

Moisture was even plentiful in Southern California. At least nine daily rainfall records were broken in the Los Angeles area on Dec. 30, including an 85-year-old record of 2.34 inches in downtown L.A.

But a "wet start to the year doesn’t mean this year will end up above average once it’s all said and done," Department of Water Resources snow surveys manager Sean de Guzman said in a statement about the survey.

The agency's director, Karla Nemeth, added that "we need more storms and average temperatures this winter and spring, and we can’t be sure it’s coming."

"It’s important that we continue to do our part to keep conserving — we will need that water this summer," she said.

Much will depend on what the rest of the season has to offer. Whether January, February and March will be as moist as December depends on factors such as La Niña conditions and pressure systems off the coast, experts said.

Currently, a La Niña pattern is holding in the tropical Pacific, and forecasters expect it to persist through the winter before transitioning to a neutral pattern this spring. The pattern typically results in a drier-than-normal winter in the Southwest, as was the case in 2021.

According to Patzert, 84% of La Niña years since 1950 have been drier than average in Los Angeles.

Also of concern are warming global temperatures caused by climate change. Warm precipitation falls as rain instead of snow, and can even melt valuable snowpack, said Diffenbaugh, the Stanford climate scientist.

“The state of the drought is pending,” Diffenbaugh said, and depends in part on “how many storms we get in the coming months, how warm they are and how much precipitation and snow they deliver to which parts of the state.”

One year that could offer some clues as to what the coming months may bring is 2012, when California saw above-average rainfall and snow in December. The rest of that water year ended up bone-dry, resulting in the first year of a drought that lasted until 2017, state officials said.

According to NOAA, the short-term outlook favors below-normal precipitation and above-normal temperatures in the West through mid-January.

While Sacramento and some northern parts of the state are slated to see more storms this week, other areas, including Los Angeles, are poised to stay sunny and dry.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.