X-Men: The Hellfire Gala 2023 delivers a bad idea in a terrible way

We need to talk about the ending of X-Men: The Hellfire Gala 2023. Needless to say, spoilers on right from the jump.

What everyone thought was gonna happen has happened: Krakoa has fallen, the X-Men are dead or scattered to the wind, and the latest iteration of Xavier's dream is apparently over. In other words, as promised, 'Fall of X' has kicked off with a devastating change in status quo for mutants in the Marvel Universe.

We could get into a gut-wrenching blow-by-blow of 2023's Hellfire Gala one-shot, which depicts the gruesome deaths of fan-favorite characters including Iceman, Jean Grey, Jubilee, and many, many more. But what's far more striking, far more shocking, and frankly far more irresponsible are the broad strokes of the latest version of mutant genocide.

Orchis conducts an elaborate, pre-planned attack on Krakoa in which they use various advanced and unexpected technologies to subdue and kill the X-Men one-by-one, and then kill all the humans present. The villains reveal that they've poisoned the mutant medicines that have been distributed across the world with a "kill switch" that allows them to instantly murder any humans who have taken the mutant drugs.

The leaders of Orchis promise Xavier that they'll kill hundreds of thousands of humans if any mutants remain on Earth, leading Xavier to telepathically force all the mutants on the island - "over a quarter million," according to the comic - into the Krakoa gates to the planet Arakko. Only a few powerful mutants such as Wolverine, Nightcrawler, and Rogue are able to resist Xavier's telepathic control.

Here's where things get really, really bad.

With Krakoa essentially depopulated and mutants now blamed for the deaths of all the humans who have fallen victim to Orchis' poisoning, the old "hated and feared" status quo is resumed, with any mutants left on Earth immediately becoming worldwide fugitives.

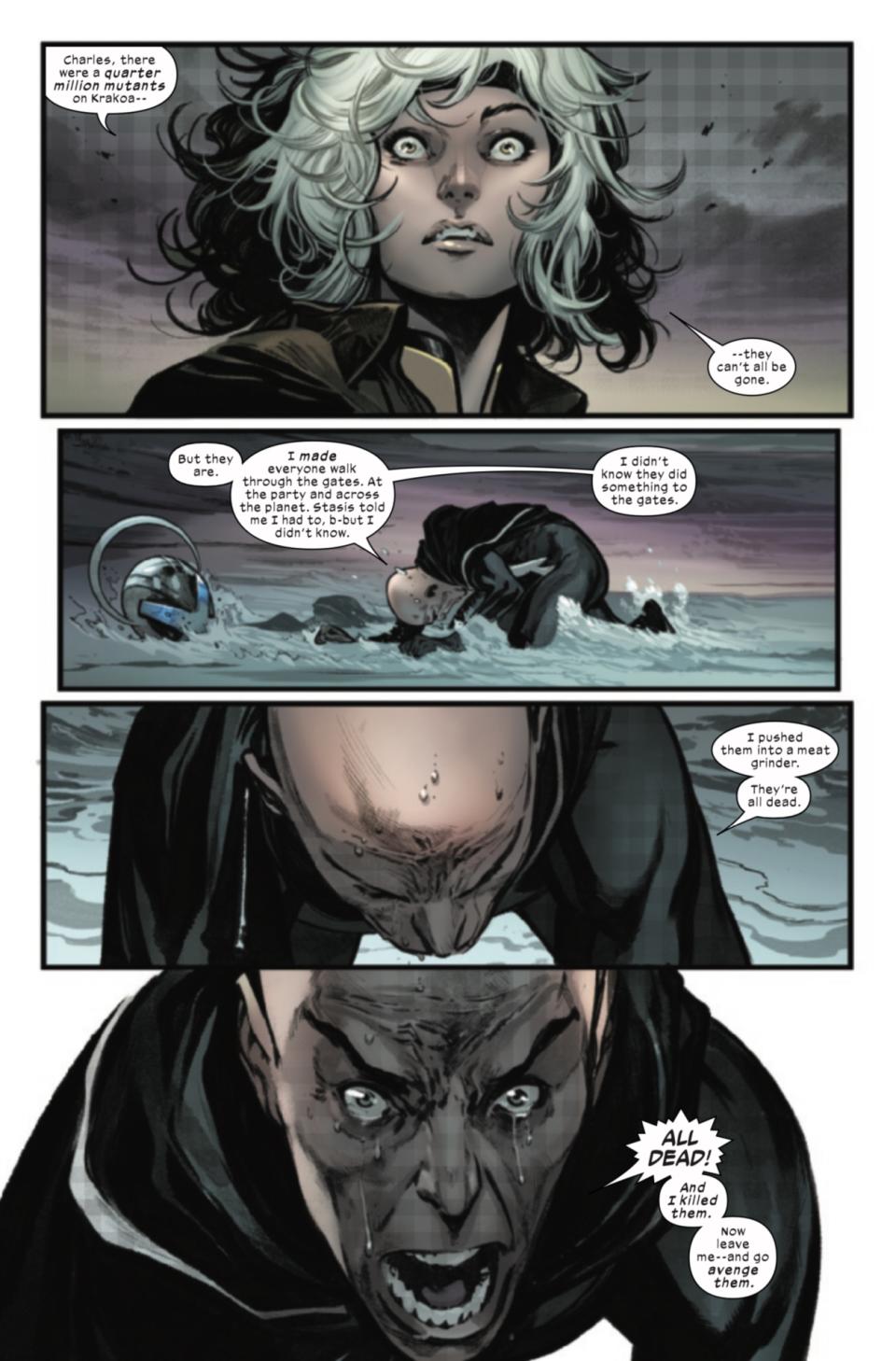

As for the mutants who went through the gates, well, according to Xavier, they're all dead. He states that Orchis "did something to the gates," and that he has lost all connection to the mutants who went through. "They can't all be dead," Rogue says, shocked. "But they are," mourns Xavier.

So… Either Marvel Comics just killed 250,000 mutants off-panel, or they want both readers and Xavier to believe they did. An entire population of mutants, once again murdered wholesale in a genocide that happens in the blink of an eye, across just a few text bubbles.

I'm not going to pretend that it's impossible or even unlikely that the situation is a fakeout and more complicated than the genocide of a quarter of a million mutants. But reading those lines, especially after witnessing the most powerful mutants in the Marvel Universe rendered essentially helpless against bigot murderers, I had a truly visceral reaction to the very concept.

I'm also not going to be so naïve as to imagine that a kind of nauseated horror isn't exactly the kind of reaction writer Gerry Duggan and the over-a-dozen artists and colorists who worked on the one-shot meant to produce. There's a sense of genuine heartbreak, sorrow, and even fear generated by 2023's Hellfire Gala that is the direct product of the book's creation and artistry.

But is that a good thing?

The central message in the story is that Orchis hates mutants, sees them as different, wishes to marginalize and even physically destroy them. They are an out-and-out hate group rendered on the comic page, a direct reflection of the so-called 'mutant metaphor' of the X-Men as stand-ins for real marginalized people that is a necessary part of Orchis' mission.

The problem then is that watching a fictional hate group commit fictional mass violence against a population of fictional marginalized people feels a lot like inviting readers to witness a hate crime. The thrill that comes from 2023's Hellfire Gala feels a lot less like a tragic superhero story and way more like standing inside the carnage of the very real hate crimes that currently fill the news in the United States on a seemingly unending basis.

Marvel is forcing the 'mutant metaphor' back to the forefront by resuming the X-Men's long-past-its-expiration-date "hated and feared" status quo, once again only embracing the concept of mutants as marginalized people in order to widen the impact when Marvel, a publisher primarily led by people who don't share in the metaphor, decides a genocide is in order. It's ugly. It's hard to read. It's disheartening.

I'm not accusing Gerry Duggan or Marvel editorial of anything but failure to consider the long view. I don't think Duggan or any of the creators involved are expressing a repressed attitude towards some marginalized group.

I do think they're not really considering how it feels to be, say, a trans person reading this story, watching what mutants have built for themselves be destroyed while hundreds of thousands of them are apparently killed off panel with a few word balloons, while in the real world legislation is increasingly targeting the lives and liberty of actual living trans people across the United States.

Fiction should reflect life. Stories should be told that confront difficult and even horrifying topics. There is a place where these metaphors should be explored and truths should be exposed through works of fantasy.

But it's feeling more and more like Marvel Comics only wants to acknowledge those ideas when it's time to destroy them, without thought for how the metaphor actually reflects the real world and the people in it.

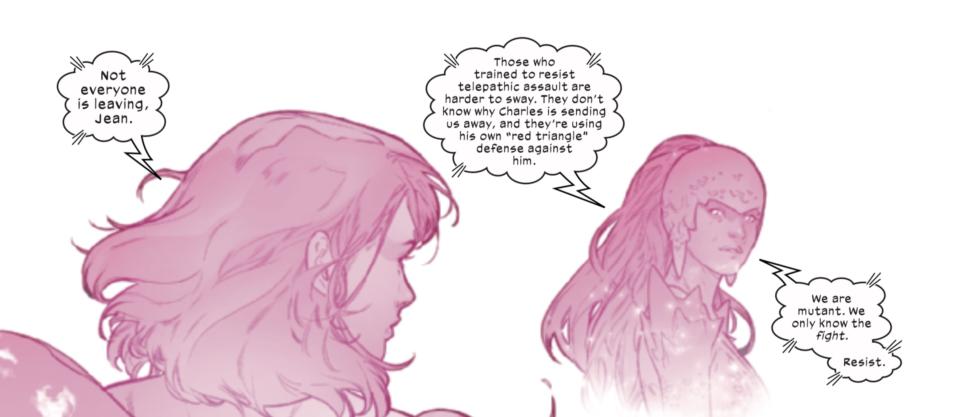

"We are mutant. We only know the fight. Resist."

These are some of Jean Grey's last words as she dies, psychically steeling Firestar for her role in the post-Krakoa future. But they read far more ominously than the script likely intends, because they belie the real-world neoliberal approach to "co-existence" that is intent on always casting marginalized people to the side, asking us to "resist," and promising us that they're doing all they can to slow down a moving train of violent bigotry without ever actually putting on the brakes.

This makes Jean's line come off almost like a bad punchline - an expression of the "best we can do"-style politics of the real world. It may as well come with a hashtag.

Marvel's 'mutant metaphor' asks marginalized people to see ourselves in the X-Men, to project a fantasy of personal power onto our own circumstances. It flattens narratives of real-world bigotry in favor of superhero drama. But the end point is always the same: hated and feared and hunted. Genocide. It hurts to be asked to see myself in a population that, even in fiction, can't be allowed to move on from an existence of desperation and the ramifications of bigotry.