Whatever happened to Mischief Night?

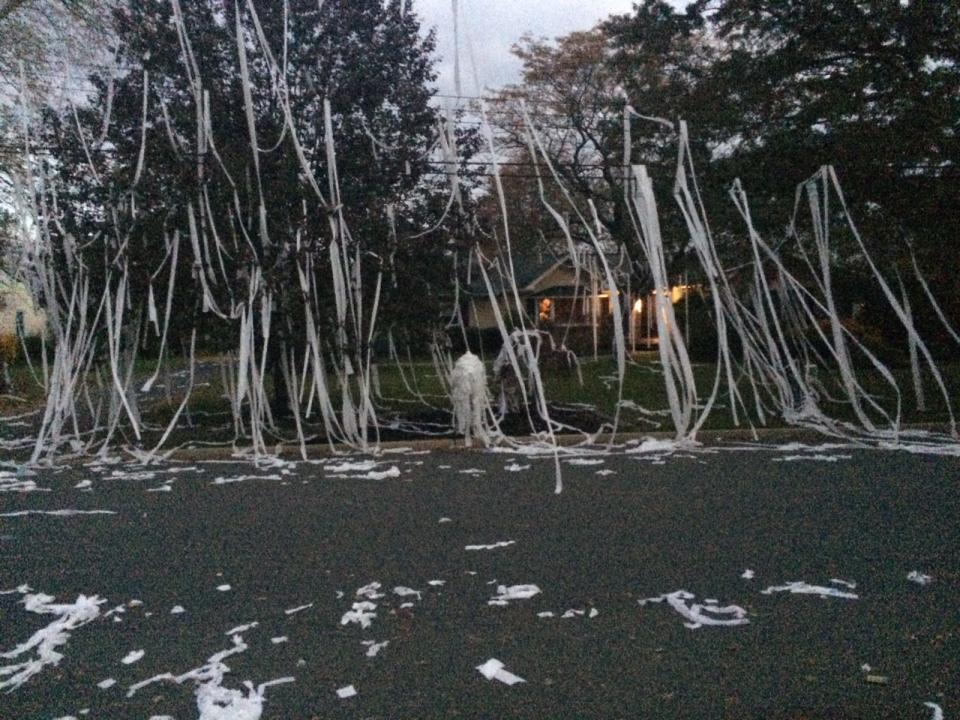

Eggs. Soap. Toilet paper

Sounds like a grocery list. Or just possibly, your front yard, at the end of October.

"Mischief Night," also known regionally as Goosey Night, Cabbage Night, Devil's Night, and Gate Night, is not the October 30 tradition it once was — a fact that Chief Michael Foligno, of the Elmwood Park Police Department, views with some relief. And maybe a little regret.

"Over the years, it's declined steadily," he said. "In the last 5 to 10 years, kids hardly come out anymore."

The average 10- or 15-year-old kid, today, probably doesn't even know that the night before Halloween is, semi-officially, a delinquent's holiday — a night when windows are soaped, cars are egged, and toilet paper is strewn across lawns.

"I've been in the police department for 33 years, and I've seen that night change dramatically over the years," said Foligno, a lifelong Elmwood Park resident.

"When I first came on the force, we had to have double the manpower on," he said. "The kids were so mischievous. One night they actually overturned a car and lit it on fire. This was back in the early '90s."

Those nights were a headache for the department — and more so for the morning shift, which had to handwrite each individual report of vandalism. "You ended up writing 15 reports of all the property damage from the night before," Foligno said.

Going easy

There may have been one beneficial side-effect, though. Mischief Night was a rare instance where police and lawbreakers got to see each others' best side.

For the police — some of whom, like Foligno, might remember having soaped a few windows in their day — it was a reminder that criminal impulses are common to the best of us.

Youthful evildoers, meanwhile, got to see the cops at their most lenient.

"We weren't super hard on the kids," Foligno said. "We kind of gave them a little leeway, unless they pushed the envelope."

And some kids did push the envelope. A burning car isn't mischief, it's a crime. And there are places where Mischief Night got even more out of hand. "Devil's Night" in Detroit, in the 1980s, was famously like something out of "The Purge." In 1984, more than 800 fires were set.

"It had to do with a lot of vacant properties, and some tensions that are specific to Detroit," said Halloween expert Lesley Bannatyne, author of "Halloween Nation" and other books.

Where did Mischief Night come from? That's as mysterious as where it went.

But it probably has its roots in the "carnival" idea that has been with us since the ancient Romans — a release of the social pressure-valve that can also be seen in such latter-day festivities as Mardi Gras and April Fool's Day, Bannatyne said.

"Things are upside-down," Bannatyne said. "The fool is king. Nobody's property is sacrosanct."

An old idea

On Halloween, long before trick-or-treating was invented (more recently than you think), kids were traditionally up to no good.

Old movie fans may remember the nostalgic 1904 Halloween scene in "Meet Me in St. Louis" (1944) when little Tootie (Margaret O'Brien) rings the doorbell of grumpy Mr. Braukoff and throws flour in his face. "I killed him!" she shrieks.

Jack-O'-Lanterns, originally, were not placed on the porch steps for decoration. They were used to scare people. "Kids would steal a pumpkin, carve a face in it, put a candle in it, and sometimes they would put it at the end of a stick and float it past someone's window, scare them to death, and then run away," Bannatyne said.

Stranger Jersey:The Urban Legends of N.J.

It wasn't until the 1920s that the endearing form of blackmail known as "trick or treat" first appeared. And it wasn't until the 1940s and 50s that it became commonplace, and its parameters fully set. As late as the 1944 film "Arsenic and Old Lace," the two loveable old aunts are seen handing, as favors to trick-or-treaters, not candy, but.. pumpkins.

Meanwhile, as the 1930s wore on, there was an attempt to tame Halloween — to de-couple the disreputable aspects of the holiday from the innocent fun.

"There was a massive national push to stop what was known as the Halloween problem," Bannatyne said. "There were civic organizations that did everything they could to get kids indoors at night, and stop the worst of the tricking."

But rather than disappearing altogether, all the sign-stealing, dumpster-fire-setting, and shaving-cream decoration began to be shunted off to an unsanctioned, pre-Halloween holiday. October 30. Mischief Night.

"Where I grew up in Southern Connecticut, it was called Doorbell Night," Bannatyne said. "It was the night before Halloween. We rang doorbells and then ran away."

The greatest prank of all

Of all Mischief Night pranks, the most famous was one of the first.

On Oct. 30, 1938, Orson Welles broadcast his famous "War of the Worlds" production on CBS radio. About 12 million people heard the realistic drama, written in the form of news bulletins. Of those, about 1 in 12 were convinced that Martians really had invaded Earth and were in the process of leveling New Jersey and Manhattan.

The resulting panic is legendary — though Welles couldn't have known quite what he unleashed, when he delivered a winking tag line at the end of his "holiday offering."

"Starting now, we couldn’t soap all your windows and steal all your garden gates by tomorrow night," Welles said. "So we did the best next thing. We annihilated the world before your very ears, and utterly destroyed the Columbia Broadcasting System."

FYI:How to stay safe this Halloween

By the 1950s and '60s, Mischief Night was every bit as much of a problem as Halloween had ever been. "There are newspaper articles where the town council meeting had to be rescheduled, because the counselors had to be in their houses to prevent mischief," Bannatyne said.

Like other suburban towns, Elmwood Park had its share of these merry pranksters. Back in the day, Chief Foligno was one of them.

As a teen, he'd go out on Goosey Night — as many in North Jersey call it — with members of his wrestling team.

"We would meet up at a certain location, on the intersection of Gilbert Avenue and Speidel Avenue," he recalled. "It's a wooded area in town, and we knew that if the officer came, we could run into the woods and it would be hard for them to find us. We would walk through the streets and throw eggs and use shaving cream, and soap the windows. Harmless fun — but I guess it was annoying to the residents."

On the way out

Kids still go in for Mischief Night in some places — but not nearly to the extent that they did a generation ago, Foligno believes. Perhaps the change, as in so much else in the culture, has to do with the Internet. Kids aren't outside having good, unwholesome fun.

"Kids hardly come out anymore," he said "It's all the tablet, cellphone activity. This generation didn't grow up in the outdoors. They're more indoor kids, now."

Another explanation could be all the security-cams that now poke out of doorways and gateways.

But Foligno isn't so sure about that. He knows the minds of juvenile pranksters. He was, after all, one himself. Kids aren't that calculating.

"They aren't thinking that way," he said. "You still have adult criminals on porches, stealing Amazon packages. If adults don't think that way, I don't think kids are going to think that way."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Mischief Night: Is Oct. 30 tradition a thing of the past?