Teaneck's first Black policeman was a 'model cop.' He can still teach us | Mike Kelly

Imagine a cop who didn’t carry a gun.

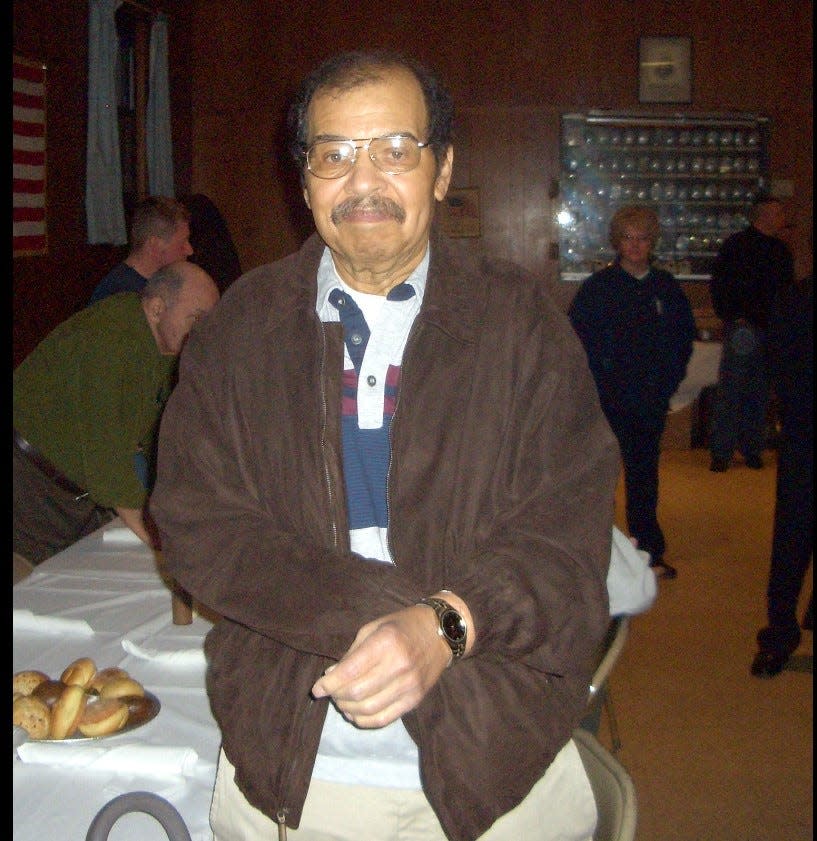

Such was the legacy of Freddy Greene of Teaneck, the town’s first African American police officer who spent most of his career patrolling the streets without a gun.

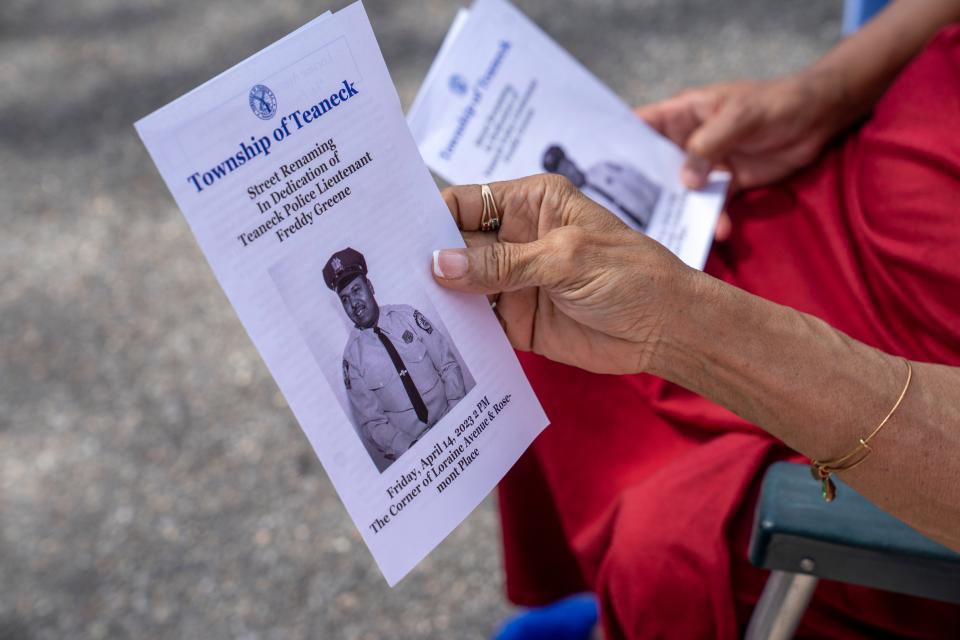

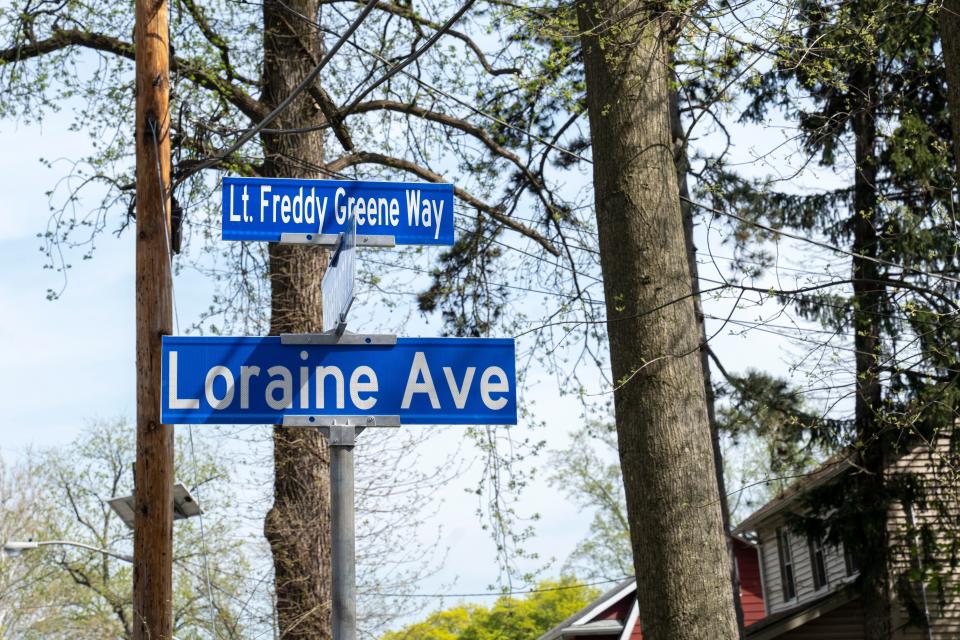

Greene’s hometown was set to honor him Friday by adding his name to one of the town’s streets. But Teaneck is not calling this a “street” or a “lane” or even a “boulevard” or “avenue.”

It’s simply "Lt. Freddy Greene Way” — with an emphasis on “way.”

To understand Greene, who was 70 when he died in May 2008, it’s important to understand his way of policing that started with his decision to go about his work without a gun on his hip.

Why did he take such a risk? What impact did it have on his community?

We hear much now across America about the need to reform policing. But how? With some proposals seeming noteworthy and some not, perhaps it’s worth looking back on a cop in a suburban North Jersey community who declined to carry a gun.

For example, what would Freddy Greene think of proposals, largely from Democratic progressives in the midst of rising crime rates, to massively cut police budgets? Or former President Donald Trump’s call, in the face of criminal probes into his own questionable behavior, to defund the FBI?

My guess is that Greene would not favor such naïve ideas. But setting aside the outlandish defund-police proposals are several others that seem far more grounded in real life — and, in all likelihood, would fit into the “way” of Freddy Greene.

Earlier: Teaneck to honor and remember Freddy Greene, township's first Black police officer

'What we call social work now'

Here, in New Jersey, for example, state law enforcement authorities are leading an experimental program to create teams of local cops and social workers to show up at emotionally stressful confrontations that in the past were the domain of heavily-armed SWAT teams. Other communities — notably Camden, the former “murder capital of America” — are refining so-called community-policing efforts that include reassigning cops from patrol cars to walking beats in which they are required to actually talk to local residents.

Forty years ago in Teaneck, Greene was already experimenting with variations of such programs.

Greene’s style in Teaneck set an example for his generation of cops — and caught the attention of more than a few citizens too. Simply put, Greene brought a sense of humanity to police work that extended far beyond the rules, regulations and rigid methods that often force cops to behave like robotic characters rather than real people.

Greene’s decision to not carry his service weapon in public was the most notable. It earned him the respect of many cops. But if truth be told, some cops were also shocked, too. Some even laughed derisively.

How could a police officer not carry a gun?

If you stopped the narrative of Freddy Greene’s life with such a question, you would not fully understand his “way.”

Yes, Greene became known as the cop without the gun. And it’s certainly worth admiring Greene for taking such a bold stance in his work as a cop. Not carrying a gun became Greene’s symbolic badge — almost a character trait or conversation-starter with people. Think of Greene as a suburban Jersey "Columbo."

But Greene was not naive. He knew policing was dangerous. So he often made sure that armed officers were always close by in case he ran into trouble.

“The cavalry was always near,” one officer said.

Coupled with Greene’s decision to venture in public unarmed, he brought along other weapons — namely, his unique ability to size up people and situations long before they escalated to a point where violence erupted.

As William Broughton, another African American officer who followed Greene into the ranks of Teaneck’s police and rose to the rank of captain, noted, “He relied on a lot of other tools.”

“What Freddy was doing was what we call social work now,” said Broughton, who later became a Bergen County undersheriff and Teaneck township civilian manager before taking up his current post as the public safety director in Long Branch.

“Most people knew Freddy in the community so he could use some of his other tools — namely, his ability to talk to people,” Broughton said in an interview. “Most people probably didn’t recognize that he wasn’t armed.”

To Greene, a crime scene or a guy in handcuffs who had just been hauled into the police station did not just involve a possible violation of the law. Maybe there was a broken personality to understand, perhaps a deep sadness that was causing someone to misbehave in such a way that police had to be summoned.

In short, Greene, who also volunteered as a community youth counselor, looked beneath the obvious signs — and crimes — to understand the sometimes convoluted factors that guide human beings to do strange things.

What can we learn from Camden?: If Paterson wants a new police force, it must look to this NJ city

More Mike Kelly: These tactics might have prevented Najee Seabrooks' death

'Freddy listened'

As America now confronts a tragic fact of modern life, cited in a recent report on police reform by the Brookings Institution, that one-quarter of all victims of police shootings in America suffer from some form of mental problem, it’s hard to say whether Greene made a difference.

Police are terrific at compiling files on speeding tickets and burglaries. But police don’t necessarily keep track of when a cop has a meaningful conversation with an ordinary citizen that builds trust or whether a cop’s conversation with an emotionally disturbed person – or even just someone who was having a bad day – made any difference. Those kinds of records never make it to the annual crime reports.

But this was the kind of police work that Greene perfected.

“He was ahead of his time,” said Paul Tiernan, a former Teaneck police chief who knew Greene well.

“Freddy listened. That was his big thing,” said Tiernan, who recently retired as chief of police in Newark, Delaware. “He was never in a rush. He didn’t just ask for the facts but he wanted the feelings behind them.”

Pointing to Greene’s penchant for experimenting on the fly with innovative tactics, Tiernan cited the much-repeated, near-legendary moment in which Greene summoned Teaneck’s fire department to deal with an emotionally disturbed man who seemed violent. Instead of sending in police officers to subdue the man — and perhaps injure themselves or the suspect — Greene asked firefighters to turn on their hoses.

After soaking the man — and calming him — police moved in.

Tiernan also described how Greene would take rookie cops into his office and talk for hours about how the by-the-book, often-militaristic training of the police academy did not always work well on the streets of a community such as Teaneck, with all manner of racial, ethic and religious groups.

Teaneck is home to more than 80 nationalities. In 1964, it became the first American community to utilize busing of students from diverse neighborhoods to desegregate its elementary schools.

Even after retiring in 1988, Greene would welcome countless officers to visit his home on Loraine Avenue for informal counseling. Often the subject turned to how cops should deal with the town’s multi-faceted cultures.

“Freddy would treat everyone like a little brother or a little sister,” Tiernan said in an interview. “If there was a lesson he tried to pass on it was to be compassionate. Just be compassionate.”

Greene was not always popular.

In 1986, Greene publicly complained when he was passed over for a promotion to captain.

"I feel discriminated against that the final choice was made without anyone meeting with me," Greene said at the time. "I'm not telling them they have to make me captain. All I'm asking for is a shot, and that they treat me like everyone else. "

In 1990, after a white Teaneck police officer, Gary Spath, was indicted for manslaughter for fatally shooting 16-year-old Phillip Pannell, who was Black and carrying a starter's pistol that had been reconfigured to fire lethal rounds, Greene tried to find a middle ground and called for a public trial.

"It's probably in the interests of everyone, including Gary, that we examine it in a free and impartial forum," Greene said in supporting the trial. "While Gary and his extended family have to bear the strain of this for a few more months, and you can't help but feel for everyone involved, to do otherwise would leave an atmosphere of suspicion and of doubt in the minds of many people. "

Police who supported Spath were aghast, saying privately that Greene betrayed them. But many Black activists who regularly marched through Teaneck in the wake of the shooting criticized Greene for not taking a stronger position to support fellow African Americans.

In February 1992, Spath was acquitted by an all-white jury after an emotionally charged trial at the Bergen County courthouse in Hackensack. Several years later, Greene ran for a spot on the Teaneck township council but was defeated, in part because some white voters resented his support for Spath’s trial and Blacks felt he was not forceful enough.

Much of this painful history will be forgotten by the renaming of a street in Greene’s memory — rightly so.

Freddy Greene changed policing and his community.

“He was a model cop,” said his former colleague, William Broughton. “He was a model person.”

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for the USA TODAY Network as well as the author of three critically acclaimed non-fiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in the northeast, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Teaneck NJ Freddy Greene police officer legacy