The Supreme Court’s Conservatives May Be Set To Kneecap Federal Regulations

With the Senate stalled on passing President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better legislation — and as Congress is poised to fall under Republican control again — the only medium-term hope for action to combat climate change may rest with the federal government. But in a matter of days, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case challenging the Biden administration’s yet-to-be announced carbon emission regulations for power plants. The outcome will determine not only the fate of those specific regulations but also whether the federal government can implement any rules or regulations covering a wide array of economic activity beyond just climate.

In West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, a coterie of coal companies and the state of West Virginia are asking the court to preemptively prevent the EPA from reviving carbon emission regulations first proposed in the Obama administration. Those regulations were shelved after Donald Trump took office in 2017, but the Biden administration has begun the process of bringing them back.

The case presents the court’s conservative supermajority with the opportunity to crush the ability of the federal administrative state to enact regulations over economic activity even if Congress had delegated that power to it.

Congressional “delegations” come in legislation authorizing an agency to write rules covering a specific activity as the need arises. One such delegation is the authority Congress granted to the EPA in the 1970 Clean Air Act to regulate polluting emissions. The EPA’s yet-to-be proposed regulation of carbon emissions at power plants is an example of the agency adopting new regulations based on an updated understanding of what is a polluting emission.

Instead of overturning judicial precedent on congressional delegations to federal agencies, the conservative bloc is expected to turn to a doctrine preempting the normal delegation review process. If the court takes this path, it will benefit both anti-regulation business interests and the court itself, as it will seize power from the other two branches to judge all regulatory actions going forward.

At issue is the so-called “major questions doctrine,” which states that agency regulations of “vast economic and political significance” must be authorized by explicit congressional delegation of authority. This doctrine has been fleshed out by conservative justices over the past decade to become a means to preempt the existing process judges use to approve or deny congressional transfers of authority and block agency regulations opposed by the conservative majority.

It now stands as the likely tool conservatives will use to prevent the federal government from taking regulatory action to fight climate change, among many other vital issues. But legal scholarship shows that the “major questions doctrine” is based on an invented history of U.S. government.

Major Questions

The major questions doctrine made its first appearance at the U.S. Supreme Court in a 1994 case regarding Federal Communication Commission regulations of telecommunications companies. It appeared with a citation to a 1986 law review article written by Stephen Breyer a decade prior to his appointment to the high court.

“Congress is more likely to have focused upon, and answered, major questions, while leaving interstitial matters to answer themselves in the course of the statute’s daily administration,” Breyer postulated.

This meant Congress was most likely to explicitly direct agencies on “major questions” while delegating to the agencies the broader authority to write new regulations on lesser matters.

The court has since turned Breyer’s law review postulation into a new doctrine that acts as an extension of the “non-delegation doctrine.” Non-delegation holds that Congress’s assigning of regulatory authority to executive branch agencies is a perversion of constitutional government that took hold during the New Deal. The non-delegation doctrine was raised only to strike down legislative delegations during the early New Deal actions of Franklin Roosevelt’s first term.

After the creation of new agencies with broad assignments of regulatory authority in the 1970s, like the EPA, the court created a process to approve or deny congressional delegations in the 1984 case of Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which challenged the loosening of environmental regulations by Anne Gorsuch, the EPA administrator under President Ronald Reagan, who resigned amid a scandal over politically biased decisions on Superfund sites.

The resulting “Chevron deference” provided a general judicial deference to agency delegations while creating a multi-step system for the court to judge whether a specific regulation was enacted without a proper legislative delegation. The court in Chevron determined that judges were not in the position of greater policy knowledge than executive branch administrators to overrule them but created a process by which to judge regulatory actions.

“Chevron deference does not give agencies a blank check,” constitutional law scholar Cass Sunstein wrote in a 2005 article. “It remains the case that agency decisions must not violate clearly expressed legislative will, must represent reasonable interpretations of statutes, and must not be arbitrary in any way.”

Conservative jurists have since turned hard against Chevron deference and, with that, the idea that judges are not in a position to know better than Congress or the agency administrators.

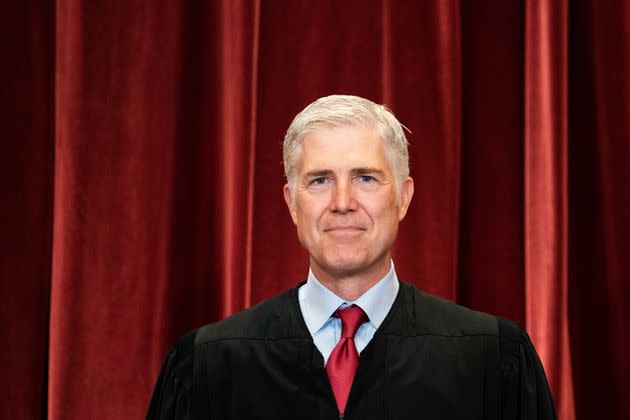

Chief Justice John Roberts declared that his “disagreement” with the current Chevron deference “is fundamental” in a 2013 dissent joined by Justice Samuel Alito and then-Justice Anthony Kennedy. Justice Neil Gorsuch, the son of Reagan’s former EPA chief, holds himself up as the foremost opponent of Chevron deference.

It was notable, then, that Gorsuch’s concurrence in the recent Supreme Court decision striking down the Biden administration’s vaccine-or-test mandate for large employers focused on the argument that the mandate violated the major questions doctrine because it was of “vast economic and political significance” that, he argued, Congress had not expressly authorized.

“The major questions doctrine serves a similar function” as the non-delegation doctrine, Gorsuch wrote, “by guarding against unintentional, oblique, or otherwise unlikely delegations of the legislative power.”

What the major questions doctrine provides is a tool to short-circuit the multi-step Chevron deference system. Justices may now determine that a regulatory action is sufficiently “major” prior to beginning a review under the multi-step Chevron deference process.

Such a doctrine “aggrandize[s] the courts at the expense of Congress and the executive,” Georgetown law professor Lisa Heinzerling wrote in a 2017 law review article. “They change the ground rules of statutory interpretation after the other branches have acted, upsetting the reliance the other branches may have placed in the preexisting interpretive regime and yet not replacing that regime with stable and predictable rules that could foster reliance moving forward.”

Blaming Congress

The court’s conservatives present their opposition to congressional delegations of authority to these agencies not on arguments that they provide too much power to the executive branch but that they represent a corruption of Congress.

“The framers knew, too, that the job of keeping the legislative power confined to the legislative branch couldn’t be trusted to self-policing by Congress; often enough, legislators will face rational incentives to pass problems to the executive branch,” Gorsuch wrote in his dissent in a 2019 case related to the non-delegation doctrine.

“Sometimes lawmakers may be tempted to delegate power to agencies to reduce the degree to which they will be held accountable for unpopular actions,” Gorsuch continued in his 2022 concurrence in the vaccine-or-test mandate case.

In other words, Congress hands off its sole intended role under the Constitution of legislating by delegating that authority to agencies to write regulations as they become necessary. These “unconstitutional” delegations have increased as political polarization has left Congress gridlocked and incapable of legislating, conservatives assert. Therefore, the court must step in to force Congress to maintain its virtue and not shift authority on regulations to the executive branch.

This conception of Congress, however, is at odds with congressional history. First, Congress began delegating authority to the executive branch from the very beginning of the nation, as University of Michigan law professors Julian Davis Mortensen and Nicholas Bagley have written. Such history shows that the non-delegation doctrine, and therefore the major questions doctrine, are not based in the kind of originalist argument favored by most of the court’s conservatives.

“The nondelegation doctrine has nothing to do with the Constitution as it was originally understood,” Mortensen and Bagley write. “You can be an originalist or you can be committed to the nondelegation doctrine. But you can’t be both.”

Second, the notion of Congress as solely a body dedicated to the production of legislation is not borne out by Congress’s history, early to modern. The “virtuous Congress” that jurists like Gorsuch wish to restore never existed. To read about the Congress in the conservative jurist’s mind is similar to taking a stroll down Main Street, U.S.A., in Disneyland. It is a kitsch imagination of a gloried past that exists only in the hallucinations of the nostalgic.

This Americana vision of Congress hypes “cynical and declinist notions of Congress to justify judicial self-empowerment,” trial lawyer Beau Baumann wrote in a February law paper detailing what he calls “Americana Administrative Law.”

“The literature and the law are increasingly preoccupied with a Congress that never existed as cleanly as some nondelegationists suppose,” Baumann writes.

Conservative lawyers and jurists argue that Congress’s sole function is to pass legislation, ignoring both its powers of investigation, appropriation and censure, and that under conditions of hyper-partisanship, Congress chooses delegation over legislation by pointing to the reduction in bills passed, which ignores studies of Congress showing that congressional legislative activity has been condensed into fewer bills but is not less than prior Congresses.

“The effect of this approach is something like congressional gaslighting,” Baumann writes.

Judicial Supremacy

Based on an ahistorical notion of agency delegation and a mythological conception of Congress, the Supreme Court conservatives assert themselves above the legislative process as both its critic and protector. The ultimate outcome of this pose when used to justify the use of the major questions doctrine to strike down agency regulations is the assertion of supremacy by the judicial branch over the legislative branch in the realm of legislating.

The major questions doctrine provides even greater control of political decisions for the justices as opposed to a full-scale reanimination of the non-delegation doctrine. Now conservative judges throughout the judiciary can invoke the major questions doctrine for any regulation they deem sufficiently “major.”

It goes without saying that the major questions doctrine would not implicate deregulatory or non-regulatory actions taken by agencies in the same way as actions increasing or adjusting regulation.

But the new posture of judicial supremacy poses its own problems when its arrogant application leads to unforeseen results.

For example, a U.S. District Court judge in Louisiana issued an injunction on Feb. 11 preventing the Biden administration from studying the cost of carbon emissions in federal regulations and other projects because it implicates the major questions doctrine. The Biden administration, in response, halted the issuing of all new oil and gas leases on federal lands.

This may not be what the judge had in mind, but it reveals what is happening with the major questions doctrine: a power struggle among the branches of government. If the court preemptively strikes down the Biden administration’s yet-to-be proposed carbon emission regulations on such grounds, it will be clear which branch thinks it stands supreme.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.