Student debt relief blocked, potentially hurting Black and Latino families the most

As she applied to colleges in the late 1980s, life looked rosy for Sandra Garcia, who was in the top 10% of her high school class.

But after her father became disabled following an accident at his construction job, Garcia, the oldest of her family’s eight kids in Fort Worth, Texas, found herself working three jobs to help support the family while attending college part-time in fits and starts. She took 12 years to earn her business degree, then four more to get her master’s, both from Texas Wesleyan University – the first in her family to accomplish both.

Unable to rely on her parents, she often didn’t know how she was going to make it. Apply for loans, people told her. It will all work out. As the loan interest accumulated, Garcia found herself six figures in debt.

“I didn’t have much financial support – or support, period – for college,” said Garcia, 51, a budget analyst for the City of Fort Worth. “There wasn’t anyone to tell me to not accept this loan or that loan – so I did accept.”

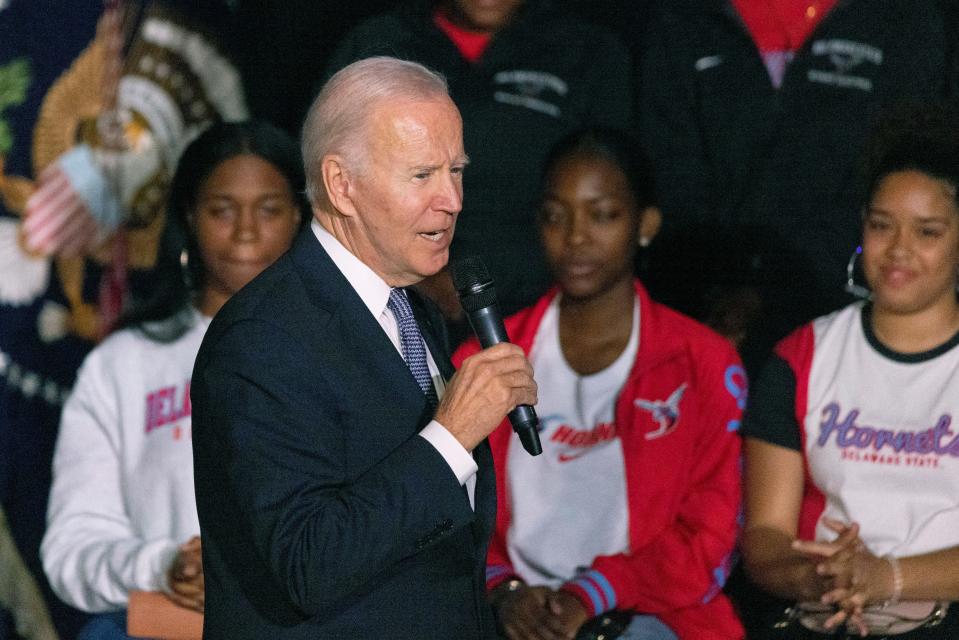

A decision from the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Monday to block President Joe Biden’s student debt relief program and another from a U.S. District Court in Texas last week could mean millions of Americans will not see their student loans forgiven. The Biden administration will likely appeal the 8th Circuit case to the Supreme Court, and some expect the court's conservative majority to ban the program from moving forward, although Justice Amy Coney Barrett has twice rejected other cases seeking to block the plan. The Department of Justice already has appealed the Texas case to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Signature Biden plan on hold: Federal student loan debt relief halted again by appeals court.

Garcia was among about 40 million Americans estimated to be eligible for the program, which would have erased up to $20,000 in debt for borrowers earning under $125,000 annually. The lawsuit was filed by six conservative states that accused the president of exceeding his authority, saying they would be financially harmed by such large-scale debt relief.

About 26 million individuals had already applied for relief, hoping to end years of loan repayments and instead apply those funds toward goals such as homes, family support and their children’s college savings.

Such debt disproportionately affects people of color, who don’t have the levels of generational wealth of many of their white counterparts. Black students in particular struggle with student debt. According to 2022 data compiled by Education Data Initiative, an education research group based in New York, Black college grads exit college with $25,000 more debt on average than white students, and four years later nearly half of Blacks owe 12.5% more than they initially borrowed.

“Students of color are less likely to get a degree due to structural practices and less likely to finish,” said Louise Seamster, an assistant professor of sociology and African American studies at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. “And they’re less likely to have a degree that will lead to a job that will offset the costs of the loan. They’re more likely to be in a position where the loan balance is going up and not down, and that can create a runaway effect.”

People of color and women in general feel pressured to pursue additional degrees to offset racial and gender discrimination, Seamster said. About 40% of Black graduates have student loan debt from graduate school compared with 22% of white college grads, according to Education Data Initiative.

“You can’t just get a bachelor’s degree,” Seamster said. “So you’re stuck trying to get an advanced degree just to earn the same amount that a white man with a bachelor’s degree would get.”

Student loan forgiveness stuck in courts: Here's how feds are still erasing debt

'People are struggling on a daily basis'

Survey results released in August showed more than 60% of voters between 18 and 34 favored Biden’s program.

Among that group is Michael Payne of Detroit, who is six figures in debt after earning his economics degree at Morehouse College in Atlanta and a master’s in education from Lesley College in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“I didn’t borrow six figures, but now it is,” said Payne, 34, director of membership and community engagement for Michigan's Black Male Educators Alliance, which recruits and trains culturally responsive educators. “Black families who send their kids to college often don’t have enough to provide for expenses, so you end up taking out loans.”

In addition to federal loans, Payne took out private loans to get through school, which not only do not qualify for relief under Biden’s latest program but whose payments continued uninterrupted during the pandemic.

Payne was able to erase about $17,000 of debt through a federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program for those working in the public sector. However, he still owes more than $20,000 in federal loans, an amount “that pales in comparison to the private loans that I took out,” he said. “In hindsight, I never would have done that.”

President Donald Trump and later Biden paused federal student loan repayments during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but payments are scheduled to resume in January after a nearly three-year break.

Loan forgiveness, Payne said, would have especially benefited people from families lacking generational wealth.

“That money can help make purchases or maybe you’re able to start a business,” he said. “It changes the dynamic of how people can live their lives when they don’t have to live with this debt looming over them. If we eliminated more student debt, we’d have a totally different economy.”

What's next?: US judge strikes down student loan forgiveness plan

In Corpus Christi, Texas, Simoné Sanders said she was “more than disappointed” by the court’s decision to block the program.

“People are struggling on a daily basis,” said Sanders, 40, who works in government relations for Texas’ General Land Office, which oversees management of state-owned lands.

Sanders studied biomedical engineering at Texas Southern University in Houston but put school on hold nearly 20 years ago to tend to her husband and grandmother, who were both dealing with severe health issues. Temporary state work turned into a career, and while she never completed her degree, she had already borrowed thousands in student loans.

Sanders had hoped to erase about $18,000 in debt through Biden’s program and focus on other expenses as she and family members open an Amazon liquidation bin store operation. Maybe she'd even complete her degree, she’d thought.

While she heard some characterize the debt-relief program as giving people a free ride, she didn’t see it much differently than the stimulus checks issued during the pandemic.

“I know if I had that money I would pay off other things,” Sanders said. “It’s not a take-advantage thing. I see it as giving people an opportunity to start planning for themselves and their families. “

Debt means delaying investments, charity

Jonathon Cerda, who recently began work as a cybersecurity software sales engineer in Dallas, Texas, called the court’s decision “unfair” given the degree to which such debt affects people of color.

“It’s directly targeting certain people,” said Cerda, 35, a 2005 high school graduate who took more than 15 years to complete his electrical engineering degree, after twice pausing to earn money as a bartender. “I wouldn’t have been able to go to school if I hadn’t gotten a lot of aid.”

His persistence paid off, and Cerda, the first in his family to graduate high school, at first wondered whether he would qualify for Biden's loan forgiveness program given his new salary.

“I would actually be able to start building wealth,” Cerda said. “You can’t really do things like invest or start side businesses or make charitable contributions if you have $40,000 to $80,000 worth of debt.”

More: How the student loan payment pause changed people’s lives

For Ciara Parks of Austin, Texas, the program would have made a difference – not so much for herself but for her siblings, she said. It took 16 years for her to pay off the student loans that got her through the University of Dayton in Ohio and then law school at Western Michigan University in Lansing.

“The problem is that you come out of school and may not have a job that pays as much as the student loans you have, and you’re trying to pay those off and do all the other things you want in life, like have a family and get a house,” said Parks, general counsel for the Texas Board of Law Examiners.

For her brother, who hoped to continue his education and go on to grad school, and her sister, who is trying to put a child through college, denial of the debt-relief program means relying on other sources to make those things happen – if they happen at all.

“For minorities who don’t come from a background of generational wealth, where it’s being passed on, a lot of us have to get student loans and makes it take longer to do some of the things that other people are already doing, like having a family or buying a house,” she said.

Seamster, of the University of Iowa, said the program would have had a huge impact, not necessarily for those with the most debt but for those with the lowest incomes.

“For them, debt is particularly onerous and can stick with them for a really long time,” she said.

How debt relief could change lives: Or how it would fall short for some

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Student loan forgiveness would have helped millions of people of color