Space photos show over 1 trillion gallons of water flooding crop fields in California, and it could mean higher food prices

Tulare Lake used to be the largest lake west of the Mississippi River.

Farmers diverted the lake's water in the 1920s and replaced it with farmland.

This year's rain and snowmelt have replenished the lake, flooding many of the region's farms.

California's heavy rainfall this past winter may have ended the years-long drought, but it also brought back the long-dormant Tulare Lake.

This phantom lake — which occasionally resurfaces during years of unusually high precipitation — is larger than it's been in 150 years.

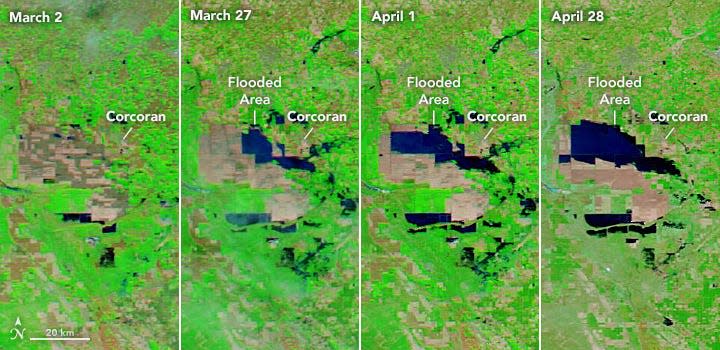

The basin began rapidly flooding around March 12-14, when two major storms hit California.

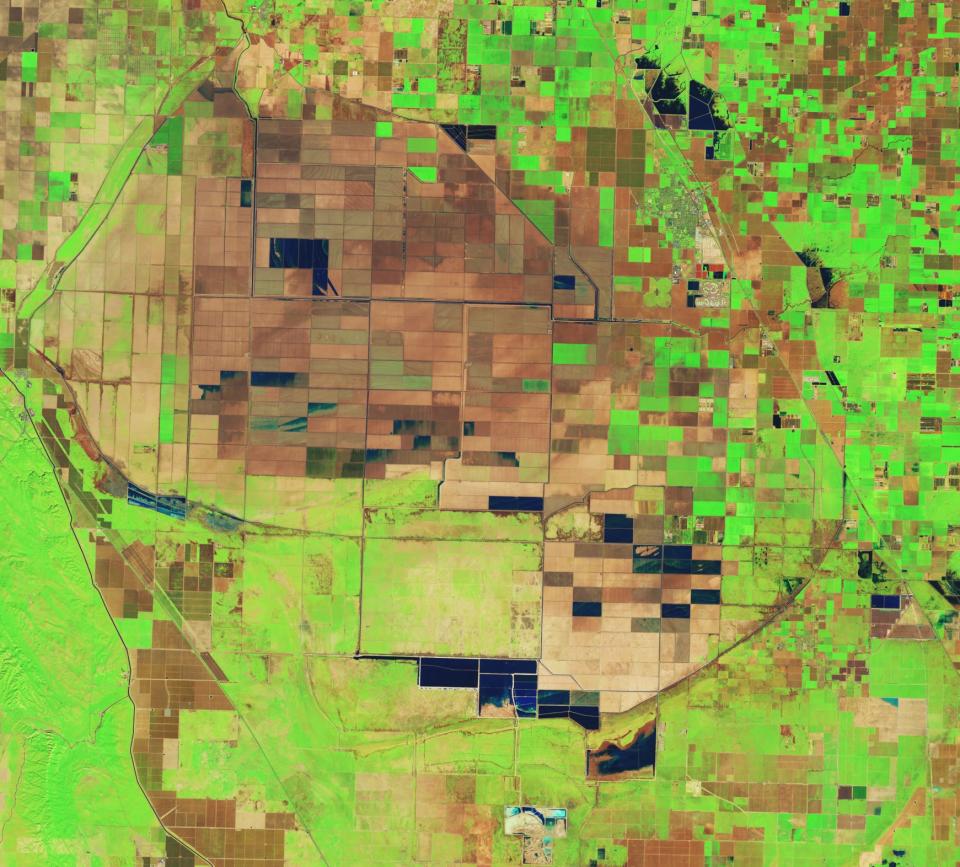

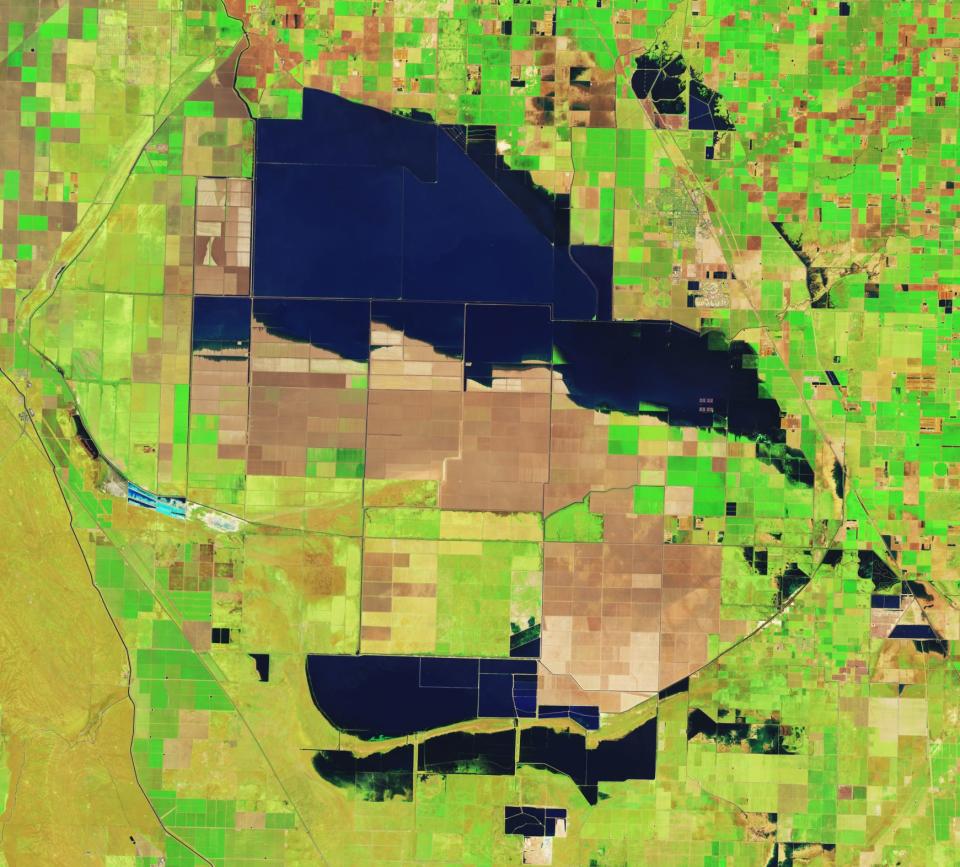

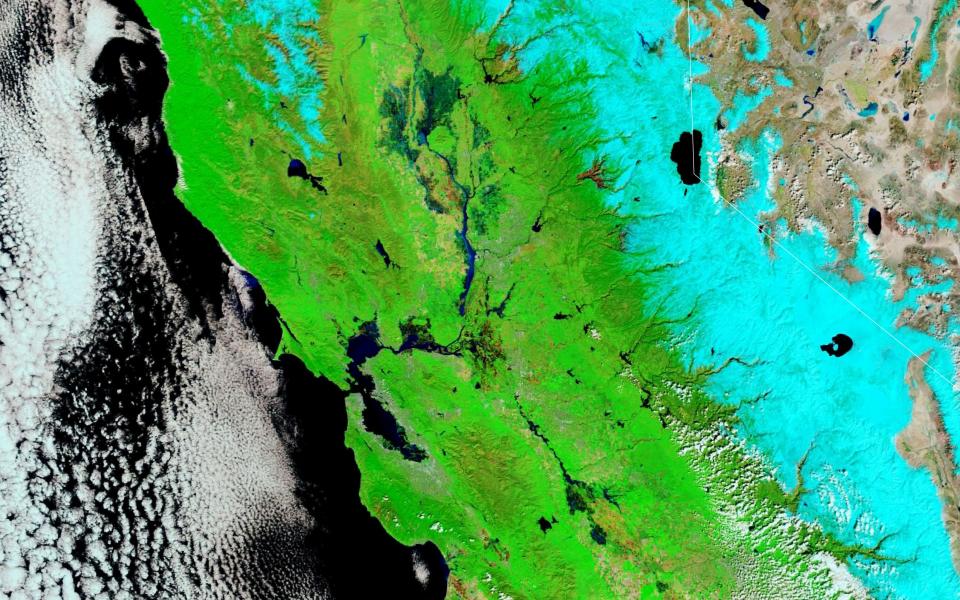

The flooding was so massive that NASA satellite images captured it from space. Here's what the lakebed looked like on February 1, before the flooding:

And here's what it looked like on April 30:

Tulare lake flooding threatens California farms

The Tulare lakebed, which is located in the southern San Joaquin Valley, happens to be set on the largest agricultural region in the entire state of California.

NASA said the devastating flooding will likely continue into 2024. That means local farmers may not be able to plant new crops until 2025.

That likely drop in supply has the potential to drive up food prices, particularly for produce.

As of June, the flooded parts of Tulare Lake spanned about 178 square miles, or 113,920 acres — almost the size of Lake Tahoe.

One acre-foot, the amount of water it takes to cover an acre of land to a depth of one foot, is equal to 325,851 gallons of water, United States Department of Agriculture meteorologist Brad Rippey told Insider in July.

While it's unclear how deep Tulare Lake is now, if it's similar to its former average depth of about 30 feet, that would translate to more than one trillion gallons of water that have flooded the region so far this year, Rippey said. That's enough to fill over 1.5 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Many of the state's top agricultural commodities are grown in Tulare County, which is the third largest agricultural producing-county in the state. In 2019, Tulare County churned out more than $7.5 billion worth of commodities, including dairy products, table grapes, navel oranges, and cattle.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated the damage from flooding across central California between December 2022 and March 2023 will cost roughly $4.6 billion.

Rippey said crops in the vineyards and orchards, like nuts and berries, will likely sustain more damage than row crops since entire trees and vines will need to be replanted.

TAC Farm sits right at the southeast shoreline of the lakebed. Fortunately for owner Dennis Hutson, the water hasn't flooded his farmland yet.

Hutson said he witnessed the flooding of Tulare Lake in 1983 and 1997. This time around, he noticed one key difference: the flooding of Highway 43 along the southern San Joaquin Valley.

"You saw water on both sides of it, but I don't recall the actual roads flooding at that time," he told Insider, adding that this unusual flooding may be due to local farmers possibly vandalizing the levies in order to drain the water from their land and redirect it elsewhere.

Rainfall and a melting snowpack: the perfect storm

Tulare Lake was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River — until the 1920s when local farmers began diverting the water from the rivers feeding the lake.

As for why the lake returned with a vengeance this spring, blame it on the 78 trillion gallons of water and counting that have fallen on California between October 1, 2022 and March 20 of this year.

By the end of February 2023, Tulare County had its fourth wettest season on record.

Nicholas Pinter, professor of applied geosciences and associate director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California Davis, described Tulare Lake to Insider as "a bathtub without a drain."

"Statewide, most flooding was concentrated in low spots in the topography, like Tulare Lake," he said during his May 23 testimony at the California Committee on Agriculture Assembly, which he shared with Insider. "After weeks of rain, the water had basically nowhere else to go."

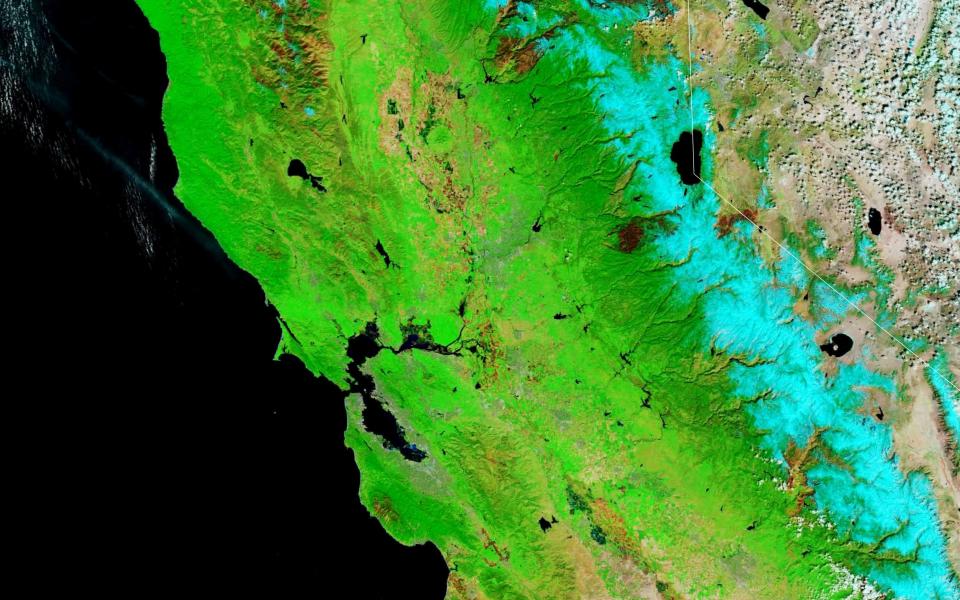

Meanwhile, the Southern Sierra Nevada snowpack reached about 300% of the typical season peak in early April — a record high.

Here's what the snowpack looked like in March 2022:

Compared to March 2023:

Tulare Lake began to reappear this March, before the Sierra Nevada snowpack started meltin. But as temperatures rise into summer and the snowpack begins to melt, that water flows into the Southern Central Valley, Rippey said.

"If the snow melts too quickly, then the valley cannot drain it and Tulare Lake fills," he told Insider. "That's what is happening now. The lake has been sustained — and even further enlarged — during the snow-melt season."

It's hard to predict how long the lake will remain, but given the recent development of El Niño, Rippey said climatological odds are tilted toward another wet winter — which could sustain Tulare Lake into 2024 or beyond.

Read the original article on Business Insider