Proposed Grand Canyon monument could turn 1.1 million acres into protected land. Here's what to know

FLAGSTAFF — About 200 people gathered at a public meeting on Tuesday in Flagstaff to talk about the proposed designation of a national monument near the Arizona-Utah border.

Supporters say the monument would protect tribal communities, heritage sites, wildlife and the watershed from the effects of uranium mining and human development. Opponents call the move an overreach by the federal government and a land grab that encroaches on private ownership in the area and could harm industries like cattle ranching.

“The threat of contaminating our water is real and current,” said Vice Chairman Edmond Tilousi of the Havasupai Tribe, one of many monument supporters to speak. “The pure water that flows through Havasupai village is under constant attack by uranium mining.”

The meeting, hosted by the U.S. Department of the Interior, was held after tribal leaders urged President Joe Biden to use the Antiquities Act to create the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument.

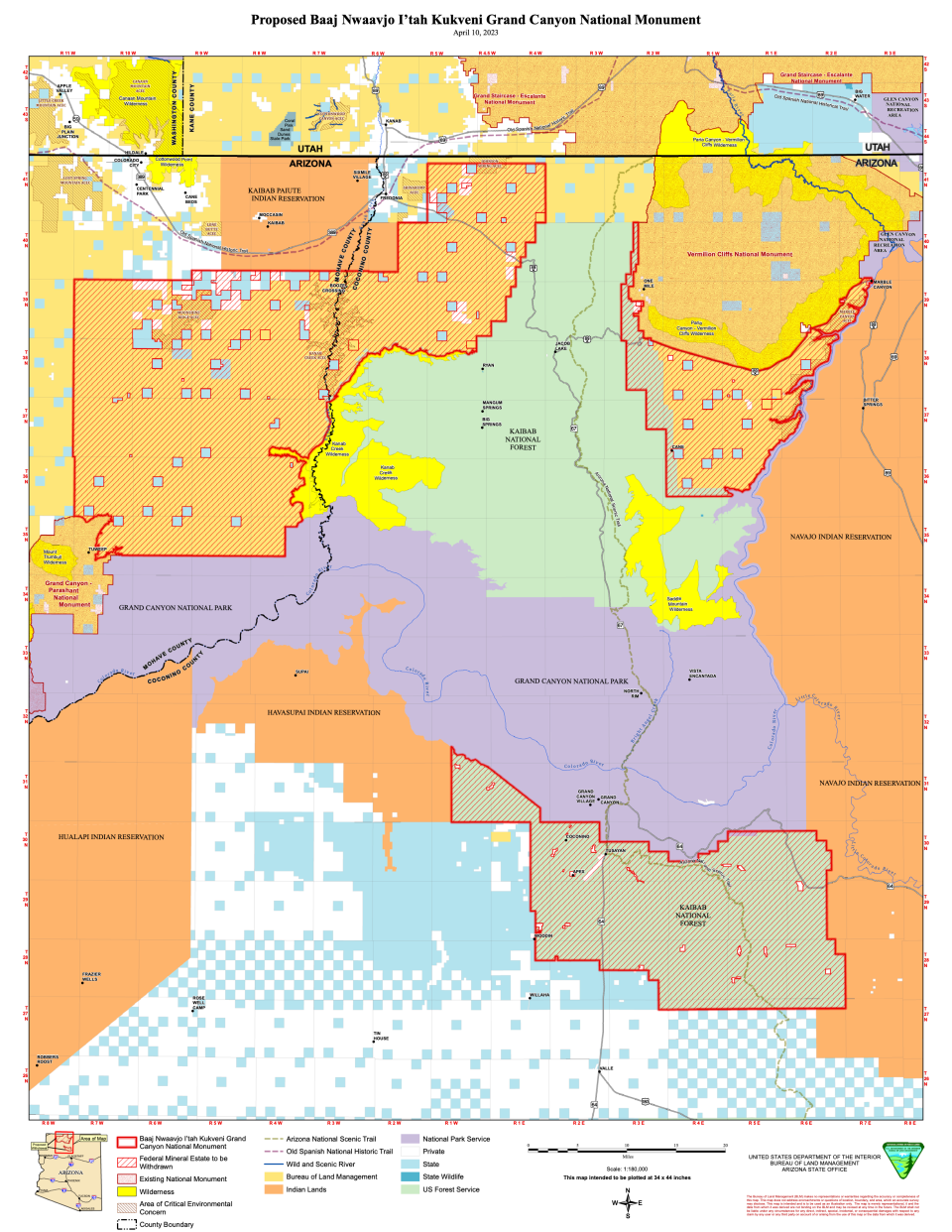

The proposed monument would encompass 1.1 million acres and would include an area in the Kaibab National Forest to the south of the canyon, as well as two areas to the northwest along the Mohave-Coconino County line, and to the northeast adjacent to the Kaibab forest.

It would also designate 12 Indigenous tribes associated with the canyon to help oversee the protected land.

“There’s such importance behind this for Hopi and many tribal nations, there’s an intimate connection we have with this,” said Hopi Tribe Chairman Timothy Nuvangyaoma. “We have to bring some protections here. I’m calling on our federal partners who are here in attendance today. You have a huge responsibility.”

The designation would honor the tribes' long-standing cultural ties to the Grand Canyon, tribal leaders said — Baaj Nwaavjo means “where tribes roam” for the Havasupai Tribe, and I’tah Kukveni means “our footprints” for the Hopi Tribe — and would protect the area by making permanent a 20-year mining ban imposed by then-President Barack Obama in 2012.

Supporters of the move include U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz., and Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., and U.S. Reps. Raúl Grijalva and Ruben Gallego, both D-Ariz., along with city councils from Flagstaff and Payson.

“Much like a human being, the waterways are arteries and veins carrying that lifeblood, to not only Arizona, but the entire world. It keeps life going,” Nuvangyaoma said. “Throughout history, native lands have been poisoned by mining and scarring. Those scars don’t heal.”

Protecting resources: Interior Secretary Deb Haaland talks with Arizona tribes at the Grand Canyon

Monument would block future mining

Part of the designation would make the 20-year mining moratorium permanent and prohibit new uranium mining in the area.

The public lands surrounding the Grand Canyon contain high concentrations of uranium ore. Mining has occurred in the area for decades and abandoned mines have harmed the environment, wildlife and humans in surrounding communities.

Uranium mining around the canyon has damaged sacred sites and polluted aquifers that feed the Grand Canyon’s springs and streams, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

Pollutants from mining uranium can also contaminate aquatic ecosystems for hundreds of years or more, threatening downstream communities, fish and wildlife.

“Once our water is contaminated, there is no way of restoring it,” Tilousi said. “Our lives will change forever.”

Since the Grand Canyon is part of the Colorado River watershed, there is concern that pollutants could enter the river that provides water for millions of people downstream.

“These lands are indeed the watershed of the Grand Canyon, feeding its fragile springs and streams and ultimately the Colorado River itself,” said Linda Hamilton, executive director of Grand Canyon River Guides. “There is a direct hydrological connection. What happens above the rim affects everything below.”

By protecting the watershed from uranium mining, supporters say, the monument would also help protect the region's fragile flora and fauna. The area is home to endangered species like the California condor and humpback chub, as well as more than a dozen endemic species of plants.

But supporters of uranium mining in northern Arizona say extraction methods used today would not pose contamination risks like they did in decades past.

Uranium ore emits radon gas, and high exposure to this gas is associated with an increased chance of developing cancer. Epidemiological studies of uranium miners showed significant excess lung cancer. During the Cold War, uranium mining poisoned soil, water and rocks on the Navajo Nation, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Since then, ventilation and other measures have been used to reduce radon levels in most affected mines that continue to operate, mining supporters say. In recent years, the average annual exposure to uranium miners has fallen to levels similar to the concentrations inhaled in some homes, according to a report from the United Nations.

Others are debating whether the proposed national monument, several miles from the Grand Canyon at its nearest point, would do anything to prevent contamination of the Colorado River watershed.

Critics say the proposal ignores local concerns

The bill introduced by Sinema would serve as a framework to work with the Biden administration if it formally proclaims the monument under the Antiquities Act, according to her office.

The legislation sets standards for the monument, including the formation of a tribal commission composed of one representative from each of the 12 federally recognized tribes associated with the Grand Canyon to help oversee the development of the monument.

But some local leaders and residents of northern Arizona oppose the designation of what would swallow more than a million acres of land in Coconino and Mohave counties.

“The move represents the Biden administration’s latest massive land grab effort and would have devastating impacts on Mojave County,” said Penny Pew, district director of Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz. “Designating another 1.1 million acres as a national monument would further reduce private ownership and harm hard-working rural Americans in Mohave County.”

Howard Ream is the mayor of Colorado City, a town of about 2,500 people at the Arizona-Utah border. He said local leaders on the Arizona Strip were left out of the conversation by the Department of the Interior.

“We want to preserve our lands, but we also want to enter in knowing how the lands are going to be managed,” Ream said. “Frankly, we don’t understand why so much of the acreage of Mohave County needs to be taken up in this monument.”

He asked the panel for a public meeting in his area, which would be part of the designation, rather than in a city miles from the proposed monument. Other county supervisors in Mohave County echoed Reams's concerns about being left out of the conversation.

A group of ranchers showed up to oppose the designation of the monument that they say encroaches on their private land and could threaten their livelihood.

“These guys have been stewards of the lands for many generations,” said Jim Parks, a former Coconino County supervisor. “Their families have been on this land. If they abuse the land, pretty quickly, they are out of business.”

They worry they will lose stewardship of federal lands leased for grazing or lose water rights. Chris Heaton, a sixth-generation rancher near Kanab, Utah, said a map of the proposal suggests he would lose private land.

According to the Grand Canyon Trust, an advocacy group, all lands within the proposed monument boundary are federal public lands, including national forest lands. No state, tribal or private lands would be included in the monument.

Two drafts of the proposal have already been released. A final draft is expected in the coming months.

Jake Frederico covers environmental issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to jake.frederico@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

You can support environmental journalism in Arizona by subscribing to azcentral today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Grand Canyon monument could turn 1.1 million acres into protected land