Price of death: What we know about execution costs as Idaho firing squad law takes effect

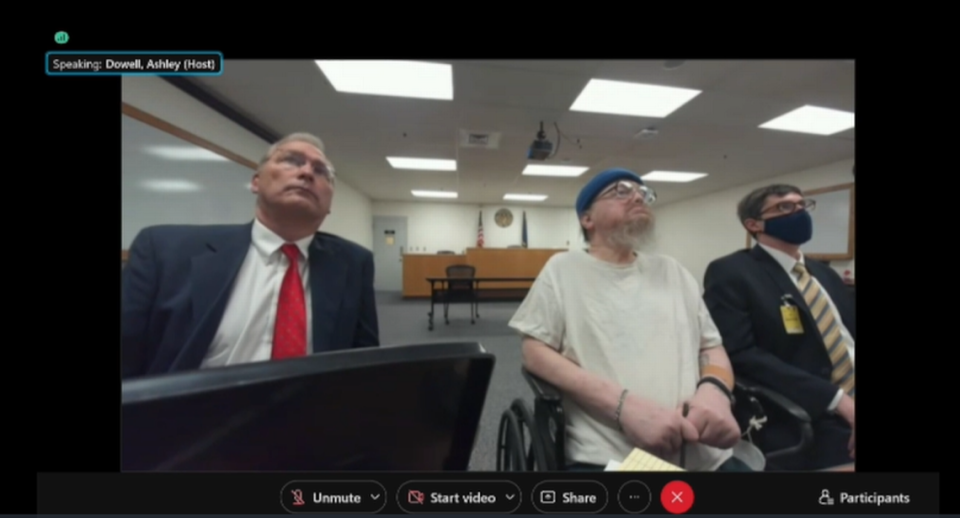

Convicted murderer Gerald Pizzuto has spent 37 years — more than half his life — locked up on Idaho’s death row. He’s dodged his scheduled execution by way of a needle five times over that period.

Since Pizzuto’s 1986 conviction for killing two people at a remote Idaho County cabin north of McCall, Idaho taxpayers have paid about $1.3 million to keep him imprisoned, according to an Idaho Statesman analysis of state prison cost records. The price to house another of the state’s death row inmates — the longest serving at more than 40 years — is nearly $1.5 million, applying 2022 per-day prison costs at the Idaho Maximum Security Institution outside Kuna.

Today, Pizzuto, 67, is terminally ill with late-stage bladder cancer and has been under hospice treatment for more than three years. A federal district judge’s stay in March of the latest death warrant for Pizzuto each day brings him closer to dying of natural causes. Should that happen, Pizzuto will have fulfilled a sentence tantamount to life in prison — but at the elevated costs connected to a death sentence, according to findings in financial studies for two of Idaho’s neighboring states.

The death penalty cost analyses, from Washington state in 2015 and Oregon in 2016, included more than a decade of data in efforts to calculate the true impact to coffers for each state’s capital punishment program. Both studies found that pursuit of a death sentence on average cost taxpayers upward of $1 million more than when prosecutors sought life imprisonment in aggravated first-degree murder cases.

Peter Collins, a professor in the criminal justice, criminology and forensics department at Seattle University, was the lead author of the two studies. Similar conclusions on these heightened costs apply to the other states in the U.S., including Idaho, that maintain the death penalty, he told the Statesman.

“If cost is what you’re looking at, not one study has shown it’s cost-beneficial from an economic standpoint,” Collins said in a phone interview. “So the question about whether it’s worth it is up to the people running the show, and ultimately maybe the voters.”

Idaho once made an attempt to study the economic costs of the state’s death penalty. The report, published in 2014 by the Idaho Legislature’s Office of Performance Evaluations, left the issue largely unsettled from a lack of data needed to conduct a more precise analysis, wrote Rakesh Mohan, longtime director of the nonpartisan legislative office.

Had a broader study been possible, Mohan wrote, he expected the same outcome as existing analyses by others on the subject.

“Collecting comprehensive data would require a considerable amount of effort and resources for stakeholders but would likely not result in anything different than what we already know from national and other states’ research,” he said. “Our study shows that capital cases take longer to complete than noncapital cases because of their inherent complexity and added statutory steps.”

The state hasn’t carried out an execution since 2012, and just two in almost 30 years. Increasingly, many death row inmates across the U.S. die in prison before they exhaust the full slate of their constitutionally provided appeals, criminal justice journalism nonprofit The Marshall Project reported.

These realities in Idaho raise questions among capital punishment critics about how the the state is using taxpayer dollars to fund the death penalty.

“They’re spending a tremendous amount of money, but the public doesn’t know, and apparently neither does the state of Idaho,” Ritchie Eppink, a Boise-based civil rights attorney formerly with the ACLU of Idaho, told the Statesman. “Regardless of one’s views on the death penalty, the public should be able to weigh in on this, and weigh in on this in a fully informed way, which we’re still not able to do.”

Idaho has eight inmates on its death row, and could soon add more. A handful of high-profile murder cases are set to move forward in the state, including with the announcement last week that prosecutors will seek the death penalty in the case of Bryan Kohberger, the man charged with killing four University of Idaho students in November.

At the same time, a new, controversial state law that allows firing squad executions has taken effect, renewing debate about the public costs of capital punishment in Idaho.

Idaho struggles to secure execution drugs

Idaho, politically dominated by Republicans, is frequently named to lists of the nation’s most ideologically conservative states, according to research and polling by Gallup. On its face, however, the push to preserve the death penalty, given conclusions about its added costs, appears to conflict with traditional concepts of fiscal conservatism, which emphasize limited government and efficient spending of taxpayer money.

“If costs of any program are inflating, then an evaluation is appropriate,” former Rep. Greg Chaney, R-Caldwell, who supports the death penalty, told the Statesman by phone. “It doesn’t necessarily mean you go in with a mindset that you’re going to repeal it. … Different people are going to expect the conversation to end in different places, but it’s definitely worth talking about.”

Idaho is one of 24 U.S. states that maintains an active death penalty program. On Saturday, it became the fifth of those states to add the firing squad as a backup method of execution.

In March, Republican Gov. Brad Little signed the bill into law with an emergency provision to take effect July 1. Idaho previously had firing squad executions on the books, from 1982 to 2009, but never used it.

Like many states, Idaho has faced difficulties securing the chemicals it needs under state law to carry out a lethal injection execution, including for Pizzuto. For several years, pharmaceutical companies and many pharmacies have refused to sell the drugs used in lethal injections to prison systems throughout the U.S.

“There’s anti-capital punishment activists that try and keep those chemicals from being available,” Little said in an April interview with the Statesman. “The chemicals are out there, it’s their availability” that’s the hangup, he said.

That challenge led the Idaho Department of Correction to pursue covert means to obtain lethal injection drugs and protect the identities of the suppliers for its most recent executions, in 2011 and 2012. In each instance, state prison officials used confidential accounts and paid thousands of dollars in cash to out-of-state pharmacies with dubious safety histories for the chemicals, as the Statesman previously reported.

The state spent more than $53,000 to execute convicted murderer Paul Rhoades in November 2011, according to the Idaho death penalty costs report. The total included as much as $10,000 for lethal injection drugs, public records showed.

Idaho spent slightly less, roughly $50,000, to execute convicted murderer Richard Leavitt in June 2012, the report said. The lethal injection drugs used in the state’s most recent execution cost upward of $15,000, the public records showed.

To aid future execution drug purchases, the Idaho Legislature last year passed a law to shield the names of all suppliers from disclosure, including through the state’s public records law. When that didn’t immediately work either to obtain the chemicals — as demonstrated by the state’s inability to execute Pizzuto — prison officials admitted that Idaho’s ability to fulfill a convicted murderer’s death sentence was effectively rendered unenforceable.

Some opponents to capital punishment argued that perhaps it was time for Idaho to rethink whether keeping the death penalty still made sense, including financially. Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador, the state’s legal representation, balked at the concept in a statement to the Statesman.

“We should not second-guess Idaho taxpayers, who have already decided through their elected representatives that the most heinous and brutal crimes deserve the ultimate punishment,” Labrador said. “Moreover, any fiscal discussion should ask why capital litigation costs what it does. Part of the reason, of course, is that the death row inmates will routinely engage in abusive litigation, dragging out the process over decades.”

In response to the latest obstacle to executions, state lawmakers, led by Rep. Bruce Skaug, R-Nampa, sought another method. Labrador, a former Republican congressman for Idaho, helped draft House Bill 186 to restore the firing squad.

No Democrats supported the bill, and the Legislature’s Republican supermajority overwhelmingly passed it, sending it on to Little’s desk.

“What good are laws if they won’t or can’t be enforced?” Rep. Wendy Horman, R-Idaho Falls, who voted in favor of the bill, told the Statesman in an email. Horman co-chairs the powerful legislative committee that sets agency budgets. “Capital punishment is used sparingly and reserved for only the most heinous crimes, and it serves the purpose of exacting justice for the victims while deterring similar abhorrent behavior from others.”

The new law requires the director of the state prison system to determine whether lethal injection drugs can be obtained within five days of the issuance of a death warrant for an inmate. If not, the execution method defaults to the reserve method of the firing squad to fulfill the death sentence.

“I wonder if the lethal injection drugs will miraculously become available now that H186 is law,” Skaug told the Statesman by email. “It is the state’s duty to carry out the sentences. The victims and their surviving families deserve to see the retribution that Idaho has deemed appropriate.”

Although the firing squad law is now technically in effect, the prison system is still in the planning stages, state prison system spokesperson Jeff Ray said by email. That process entails remodeling an area at the maximum security prison to execute inmates with guns, and developing procedures, which must be approved by the Department of Correction’s three-member board appointed by the governor.

Use of firing squad in question

Sen. Doug Ricks, R-Rexburg, co-sponsored the firing squad law. In his pitch to fellow members of the Senate Judiciary and Rules Committee, he discussed the costs taxpayers shoulder to house, sometimes for decades, the members of the state’s death row, including Pizzuto.

“We also need to consider the costs involved,” Ricks told the committee. “You can get your calculator out, do the math, times that many years by the days and by (the daily rate). It adds up to an awful lot of money.”

The daily rate for an inmate at the maximum security prison outside Kuna is about $100 a day, cost records provided by the state prison system showed. The price is the same for death row and non-death row inmates, Ray, the state prisons spokesperson, confirmed, which equates to about $36,500 a year per inmate.

Those prison costs also represent just a fraction of the total expense to taxpayers for states to pursue death sentences. Millions of dollars rack up so each death row inmate can exercise their right to appeals before they are executed.

The Washington and Oregon studies detailed a multitude of often omitted costs: court fees, attorney and staff time, trials and state and federal appeals, incarceration, execution trainings, and needed materials to carry out a death sentence, such as lethal injection drugs. Even so, incarceration costs alone on average were 1.4 to 1.6 times higher when the death penalty was sought, the Washington study found.

Overall, based on 17 years of data, the Washington study found that the average cost of a death penalty case totaled nearly $3.1 million compared with about $2 million when it wasn’t pursued. From 13 years of data, the Oregon study found the average cost of a death penalty case was nearly $2.6 million compared with about $1.7 million when prosecutors instead sought a sentence of life in prison without parole.

Deborah Denno is a law professor at Fordham University in New York City and one of the foremost death penalty experts in the U.S. She told the Statesman that widely held beliefs that lifetime imprisonment is costlier over the life of the inmate than death sentences has been proved wrong time and again.

“It’s public misinformation,” Denno said in a phone interview, specifically affirming the Washington study’s findings. “I don’t know how anybody could possibly argue with these statistics or even question them at all. It’s across the board, across the country, different states, but across different times, too, given the length-of-time cost studies conducted.”

Oregon’s death penalty remains on a governor-imposed moratorium that first went into effect in 2011. Meanwhile, Washington this year became the latest state to formally abolish capital punishment, following up on a 2018 state Supreme Court ruling that the death penalty was unconstitutional.

“I think that the recognition of the cost influenced people,” Bob Boruchowitz, director of the Defender Initiative at Seattle University’s law school and co-author of the Washington cost study, told the Statesman by phone. “Regardless of what one feels about the death penalty, if you’re spending millions of dollars to kill one person … how is that a good investment?”

Idaho’s new firing squad law also included a one-time estimated cost of $750,000 for the prison system to renovate a cell block at the maximum security prison for the new backup execution method. Ricks told his Senate committee peers during testimony for the bill that the mandatory area so observers can witness an execution made up “a lot of the cost.”

“If that was not there, it’d be much, probably less expensive to tool up to do some of that,” Ricks said.

In fact, the prior remodel of the maximum security prison’s same cell block for lethal injection executions came with a one-time cost of $170,000, according to the 2014 Idaho Legislature report. Of that, $4,418 was associated with “facility and ground improvements for the demonstrator and media areas,” the study detailed.

In an emailed statement, Ricks said the firing squad bill adds nothing to the costs Idaho expends to maintain capital punishment. The one-time prison remodel cost is very small relative to the state’s overall budget, and the facility should last for decades to come, he said.

“House Bill 186 does not impact the ‘elevated costs for seeking the death penalty’ to taxpayers prior to a death warrant,” Ricks wrote. “All those elevated costs have already been, or will be, incurred during the process specified in our criminal justice system even if House Bill 186 had not passed.”

Even with the law taking effect, Little questioned whether Idaho would ever use the firing squad to execute an inmate, still giving heavy preference to lethal injection. His acknowledgment is an early indication that the hundreds of thousands spent constructing the area at the prison for the firing squad could come without any perceivable benefit.

“This firing squad is a last result if we can’t get those compounds that are out there, and I’m thinking we will … and the firing squad won’t be necessary,” Little said. “We perhaps will need a backup to lethal injection. I think lethal injection is going to be the method that by far is preferred to get that done.”

Execution offers ‘measure of peace’ for victims’ families

Proponents of Idaho’s death penalty said they have doubts about the intent behind the economic arguments posed about reconsidering the practice.

“It is well-known that death penalty abolitionists are highlighting the expenses associated with capital punishment in a deliberate attempt to appeal to fiscal conservatives,” Labrador said. “Even assuming seeking the death penalty costs more than imposing fixed-life sentences, such costs would be justified. Capital punishment brings closure to victims of crimes and serves a deterrent effect.”

Idaho’s new firing squad law may hasten executions for the backlog of death row inmates once the legal process fully plays itself out, Skaug added.

“It is interesting how political liberals are suddenly fiscal conservatives on death penalty expenses,” he said. “Should death penalties start to be carried out more frequently in Idaho, the fiscal cost per case will become less.”

Supporting the death penalty and identifying as a fiscal conservative are not mutually exclusive or necessarily in conflict, said Chaney, the former state lawmaker. Even if studies consistently show that pursuit of capital punishment costs more than life imprisonment, elected policymakers are entrusted with how best to prioritize and spend taxpayer money, he said.

“I think that there is a time for righteous anger about the loss of life,” Chaney said. “And in those extreme cases, if it does cost more for the state to meet its obligations to at least attempt as best it can to carry out that punishment, then the cost is justifiable.”

In the case of Pizzuto’s lengthy stay on Idaho death row, he was saved from another prior execution date in June 2021 when the state’s Commission of Pardons and Parole agreed to grant him a clemency hearing. The panel later voted to reduce his death sentence to life in prison without parole, but Little rejected it. Pizzuto has bypassed two more death sentences since that time.

The Federal Defender Services of Idaho, which represents Pizzuto and the majority of Idaho’s death row inmates, declined a request for comment from the Statesman. But in past statements, the legal nonprofit questioned the innumerable costs to the state from Little’s decision, which has led the state to continue to seek Pizzuto’s execution.

“The commission voted more than a year ago to grant Mr. Pizzuto clemency and to commute his sentence to life in prison without parole so that he could live out his natural life behind bars,” Deborah A. Czuba, supervising attorney for the nonprofit’s unit that specializes in death penalty cases, said in March. “These death warrants are also becoming an extraordinary burden to taxpayers who are covering the costs of unnecessary and repetitive litigation.”

Presented with data from the two death penalty financial studies, the governor’s office sidestepped questions about elevated costs, which includes those for Pizzuto after more than three decades.

“Idaho law entrusts local elected prosecutors with the discretion to seek the death penalty for certain heinous crimes,” Madison Hardy, Little’s spokesperson, said in a written statement. “As chief executive of the state, the governor’s role is to faithfully carry out lawful sentences imposed through the judicial processes. Gov. Little supports capital punishment because it is sometimes the only way to bring justice upon evildoers and provide victims’ families with some measure of peace.”