From North Korea fighter pilot to Embry-Riddle professor: Remembering Kenneth Rowe

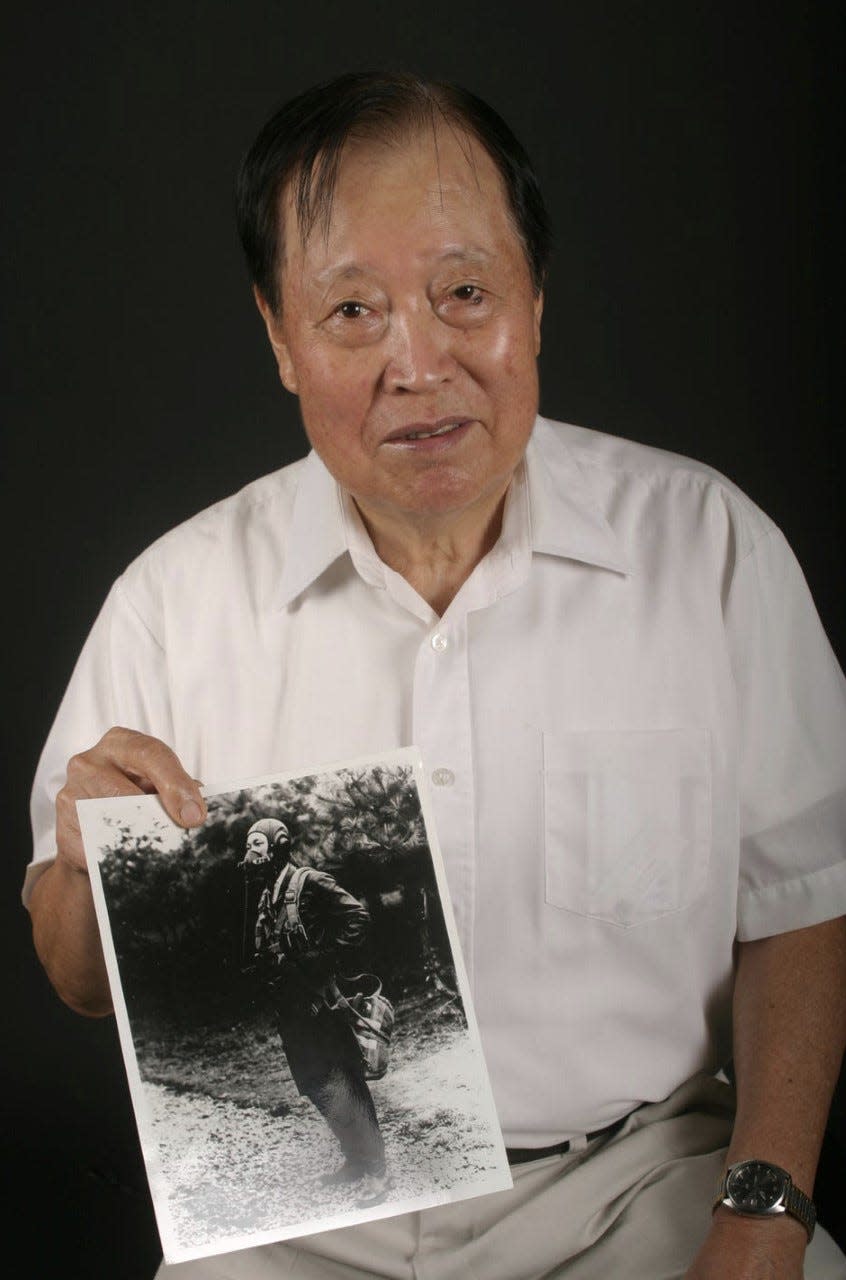

DAYTONA BEACH − No Kum-Sok's dramatic escape from North Korea by flying his MiG-15 fighter jet to a U.S. air base in South Korea in 1953 made him an international celebrity.

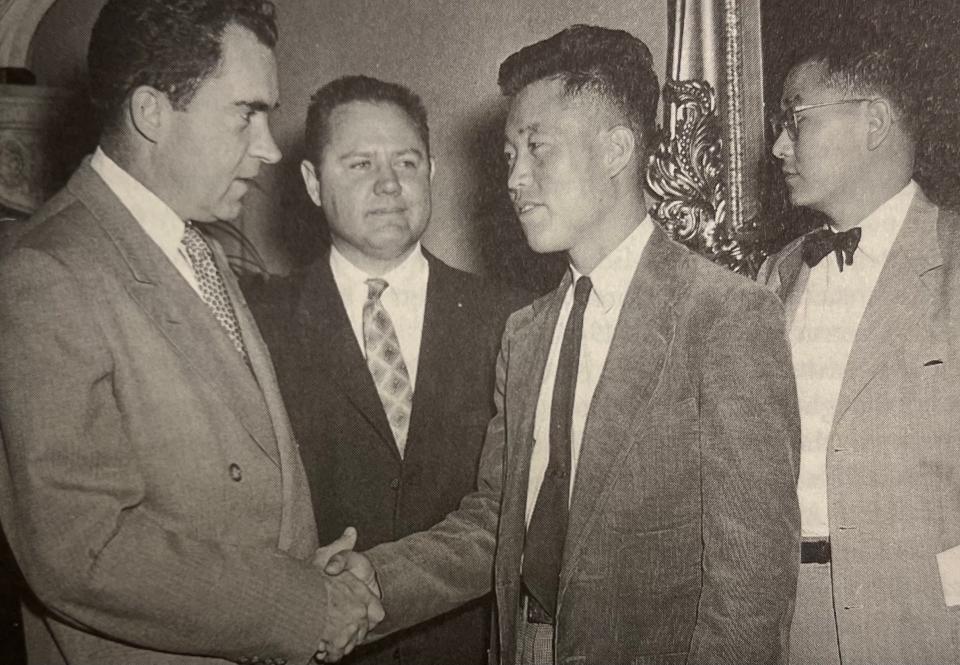

He wound up shaking hands with Vice President Richard Nixon, explaining how his Soviet-built fighter jet operated to legendary American test pilots Chuck Yeager and Tom Collins, and appeared on television shows, including "To Tell the Truth" and "Today." He also frequently spoke on Voice of America radio broadcasts.

But after moving to Daytona Beach with his family in 1983, No Kum-Sok who changed his name to Kenneth Rowe, enjoyed a quiet life as a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. He taught aircraft engineering for 17 years until his retirement and remained in the area after that with his wife Clara.

Rowe died on Dec. 26 at his Daytona Beach home, surrounded by family, just a couple weeks shy of his 91st birthday.

"He seemed to like Daytona Beach quite a lot," said his daughter Bonnie Rowe. "He liked the warm weather and he thought the people were nice."

'Wanted to be a regular American'

Kenneth Rowe's paid obituary in The Daytona Beach News-Journal once again made him the subject of international headlines, including articles in both The New York Times and Washington Post.

"He wasn't seeking to be a celebrity," said Bonnie Rowe. "He wanted to be a regular American."

Retired Embry-Riddle professor Bob Oxley remembers his former colleague as "an upstanding guy. He was open and honest. He was in favor of the kind of values Americans are supposed to have: freedom of speech and a tolerance of other points of view."

Laksh Narayanaswami currently teaches aerospace engineering at Embry-Riddle where he has been a professor since the late 1980s. He remembers Rowe most for his humor. "He laughed a lot. He was down to earth."

Kenneth Rowe in 1996 recounted his life story in an autobiography titled "A MiG-15 to Freedom," which he co-wrote with another Embry-Riddle professor, the late J. Roger Osterholm. His escape was also the subject of another book, "The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot" by Blaine Harden (2015).

Born during the Japanese occupation

Rowe was born on Jan. 10, 1932 in a small town in North Korea during the Japanese occupation. His father worked for a Japanese corporation that built and operated electric power stations and railroads. His mother was a homemaker. Both saw the United States as a utopia and beacon of freedom and did not buy into characterizations of Americans as evil enemies pushed first by the Japanese and then by the Communists who took over after World War II.

Bonnie Rowe said her dad shared his parents' views. "He was very critical about the communist system. He could see it didn't serve the common man," she said.

His father's death from cancer in 1949 left Kenneth Rowe and his mother impoverished. "He ended up joining the military so he could eat," Bonnie Rowe said.

At age 17, Kenneth Rowe began training at the North Korean Naval Academy but found the experience grueling and unbearably harsh. Cadets were fed meager meals. He jumped at the opportunity to become an Air Force cadet because he saw it as a chance for a better life − and better food.

"He thought to fly an aircraft you have to be very fit, which meant they fed you better," said Bonnie Rowe.

'Living a gigantic lie'

Kenneth Rowe became a highly decorated fighter pilot during the Korean War. He flew more than 100 missions and earned the rank of lieutenant. But he never actually shot at Americans. "He liked to just fly around and not engage in actual combat," said Bonnie Rowe.

Kenneth Rowe wrote that he suffered anxiety as a fighter pilot that he "might be forced into killing one of my beloved Americans." Instead, he resorted to firing his jet's cannon "too far away to hit anything (because) I did not want to hit anything."

The ruse worked. "Articles about my flying skill and my devotion to Communism, along with my photograph, appeared in Red magazines and newspapers," he wrote. "All that time I was living a gigantic lie."

When the armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, to halt the fighting, Kenneth Rowe saw it as his chance to finally make a dash for freedom.

Assigned to test a new North Korean air base runway on the morning of Sept. 21, Rowe initially flew his MiG-15 as instructed, but instead of returning, he abruptly veered towards South Korea.

Kenneth Rowe wrote that he knew there was a good chance he would be shot down. Fortunately, he caught the Americans off guard and safely landed at Kimpo Air Base − but only after nearly colliding with an American fighter jet that was simultaneously taking off from the same runway.

"I unfastened my oxygen mask and breathed free air for the first time in my life," he wrote. "I jumped to the ground. Then I threw the picture frame (containing a photo of North Korean dictator Kim Il-Sung) to the concrete apron to destroy it."

Rowe was surprised to learn an American General previously publicly offered a $100,000 reward to the first North Korean defector who could deliver an intact MiG fighter jet to the U.S.

Rowe said he was unaware of the offer, but gladly accepted the reward money.

The Washington Post reported that Air Force Maj. Donald Nichols in Harden's book praised Rowe as an invaluable source of information on the military operations and capabilities of both the North Koreans, Russians and Chinese. "He was able to recall air units, personnel strength, structure and number of aircraft assigned to respective units," Nichols told the author.

ANSWERING THE RALLY CALL: Community steps up to help Korean War vet in need

RECOVERED AT LAST: U.S. military retrieves war remains from North Korea

NEW HOME: War museum relocates from downtown Daytona to Holly Hill

'Incorrect to say that I defected'

Rowe bristled at being labeled a defector. "It is incorrect to say that I defected from the North Korean communist regime because I had never been a communist in my heart and, therefore, I could not have defected from an ideology I had never believed in," he wrote in his memoir. He preferred to be called "a North Korean pilot who sought freedom in the United States since his childhood."

Rowe moved to the United States in 1954 where he earned an engineering degree from the University of Delaware. Upon graduating, he embarked on a career working for "15 of the largest companies" including DuPont, Boeing, General Motors, General Electric, Grumman, Lockheed and Westinghouse.

Bonnie Rowe said she once asked her father why he kept switching jobs and moving the family. "He said, 'This is a big country and I want to see every part of it.' He didn't want to be oppressed. He wanted to go to a land where people could live freely. He was not ashamed to be a Korean, but he was proud to be an American."

Kenneth Rowe became a U.S. citizen in 1962. He also changed his name to one that he thought sounded more American. Rowe was a spelled out way of how his original surname No was pronounced in Korean. He chose Kenneth as a first name because of it started with a K like Kum-Sok. "He wanted to fit in," said his daughter.

'Famous American patriot'

Rowe in 1960 married Clara Kim who also was originally from North Korea. In addition to his daughter and wife, he is survived by a son Raymond and grandson Ben. The family followed Rowe's wishes by celebrating his life privately.

"Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University was honored to have a famous American patriot on our faculty," said P. Barry Butler, the university's president. "By fleeing North Korea and delivering an intact MiG-15bis fighter jet to the U.S. Air Force in 1953, former Lt. No Kum-Sok served the United States well. As an educator, Professor Kenneth Rowe served our students well, too. He will be remembered fondly by all who knew him."

Rowe's MiG-15 is on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: ERAU's Kenneth Rowe was once No Kum-Sok, North Korean fighter pilot