The Moment That Made the Courtroom Lose It During SBF’s Trial

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

The action really got going in Sam Bankman-Fried’s federal trial on Wednesday. The jury was finalized. The sides made their opening arguments. Sam Bankman-Fried’s parents were present, obviously; so was Martin Shkreli, weirdly. And the government began calling its witnesses, including a onetime close friend of SBF: former FTX software engineer Adam B. Yedidia.

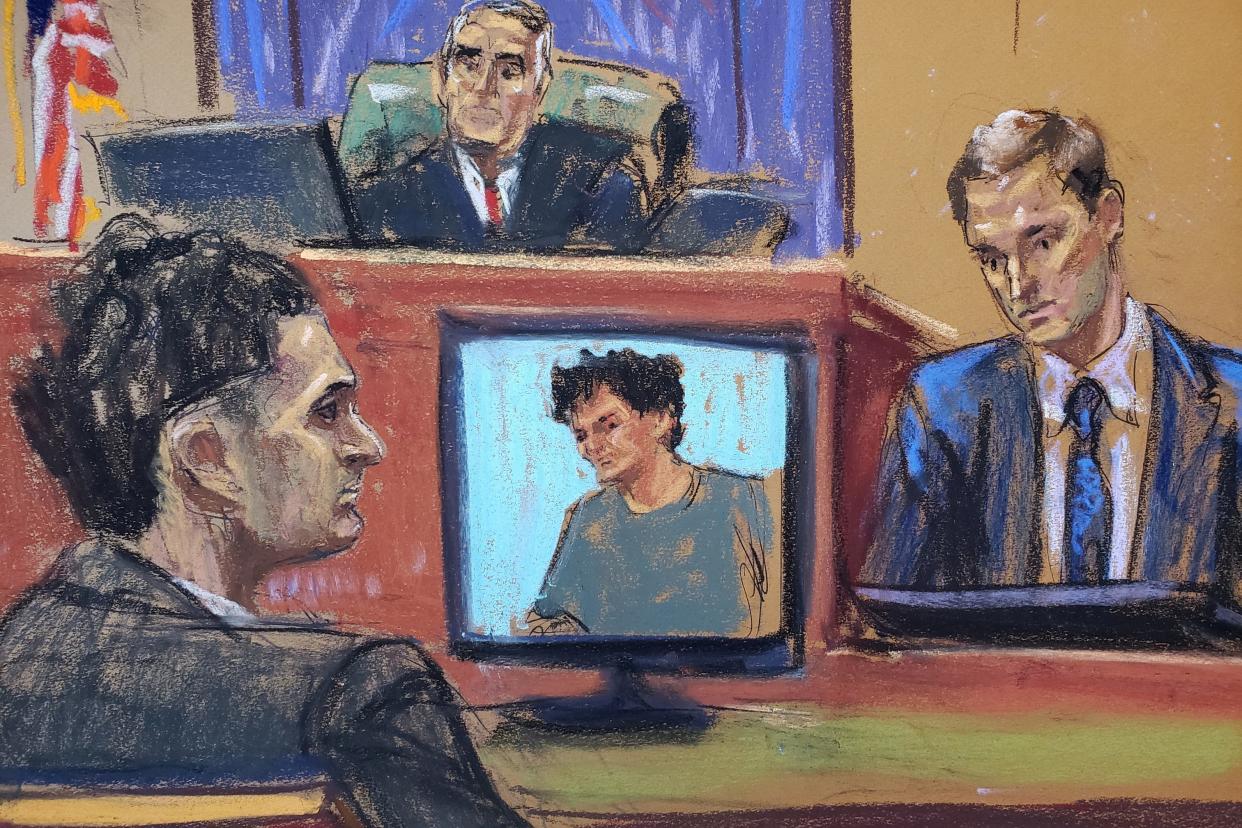

An acquaintance of the future crypto mogul from his MIT days, Yedidia exuded an earnest math-nerd vibe on the witness stand: thick-rim glasses, moppy dark hair, baggy dark suit, trails of facial fuzz, a fast-paced yet articulate speaking style. Although he was called by the prosecution, Yedidia made clear he was here of his own accord, no subpoenas or plea deals needed. He did get an immunity deal from the government, however, out of concern that “the code [he] wrote” for FTX may have contributed, in whatever ways possible, to the allegations being litigated today. Yedidia may not have been the most hotly anticipated figure in this trial—a lot of ears perked up when the government later announced that SBF deputy Gary Wang would testify this week—but he was undoubtedly an important figure in the case. Yedidia worked as a trader for SBF’s crypto hedge fund, Alameda Research, beginning in late 2017, but he didn’t stick around long, returning to MIT to pursue a Ph.D. in electrical engineering and computer science. Fast-forward to January 2021, when SBF called Yedidia again to offer him a job as a software developer for FTX. Yedidia accepted, and ended up living in SBF’s infamous Bahamas penthouse—photos of which were shown to the jury—with Bankman-Fried and eight other FTX/Alameda employees from October 2021 until “early” November 2022. [Update, Oct. 5, 2023, at 5:15 p.m.: On Thursday, Yedidia stated that he’d made a mistake in his initial testimony and did in fact receive a subpoena from government investigators. He clarified that he would have been willing to cooperate with the investigation even without a summons.]

Say, remind the room of what happened then?

It was during the infamous week in which doubts about FTX/Alameda’s insolvency went public that Yedidia uncovered something discomfiting about his workplace: “I learned Alameda had used FTX deposits to pay back loans to creditors.” What did he do then? “I resigned.” That was the last time he’d seen his once-dear friend SBF until arriving in the courtroom, Yedidia said.

The government’s lawyers made ample use of Yedidia’s time—the very last testimony of the day—to show now-notorious FTX mementos to the jury: that Forbes cover featuring SBF, that Tom Brady commercial, that Larry David Super Bowl ad. (As that last one played, I noticed SBF’s father, Joe Bankman, who had a cameo in the spot, whisper something to his wife, Barbara Fried.) The familiar mementos elicited various giggles within the room, but it was Yedidia’s confession that was most crucial to the government’s case. This allegation—that FTX and Alameda executives were using customer deposits as a bottomless piggy bank—had formed the crux of the government’s opening argument earlier in the day: SBF used customer deposits in FTX for his own enrichment, without gaining users’ explicit consent or indicating to them how he’d throw around their money, all while promising them repeatedly (through ads, website copy, and other forms of sloganeering) that their money was safe and secure in FTX accounts, and that they could take out that money whenever they wanted. The prosecution ventured that this “fraud” and “theft” allowed SBF to spend lavishly and present himself as a wealth-generating wunderkind to gullible celebrities, earning their trust and public-facing endorsements—which subsequently helped persuade more crypto-curious investors that FTX was the way to go. Yet all the while, he took fiat money and cryptocurrencies from FTX accounts and secretly funneled them into Alameda, without those depositors’ knowledge or consent, granting Bankman-Fried the ability to throw around the cash however he wanted. “This man stole money,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Thane Rehn thundered, pointing directly at SBF.

The witness who testified ahead of Yedidia was brought on to bolster that point. Marc-Antoine Julliard, a young navy-suited commodities broker based in London, told the court he’d essentially been duped by FTX’s relentless, high-priced marketing to take a chance on crypto trades within the exchange. He mentioned the Gisele Bündchen magazine ad, Bankman-Fried’s hobnobbing with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, the venture capital firms that had poured money into FTX, and the CEO’s tweets about using crypto “for good” as factors that influenced him to try FTX. Which was a mistake, Julliard now admitted. In early November, when he saw the doubts being cast upon FTX’s business, he held off on removing his FTX deposits—totaling about $100,000, between his four Bitcoins and a $20,000 fiat account—due to the Twitter threads SBF posted that week assuring FTX customers he was taking care of it and everything was fine, actually. (Those tweets were also shared as exhibits, with the prosecution also noting that SBF had later attempted to delete them.) But when he finally realized the gravity of the situation and tried to withdraw on Nov. 8, none of his requests were processed by the app. To this day, Julliard mourned aloud, he’s never been able to recover that money.

There wasn’t time at the end of the day for the defense to interrogate Adam Yedidia, but SBF’s legal team did take a moment to grill Julliard, asking him whether the prospect of crypto’s relative lack of “regulation” (as opposed to his day job in commodity trades) enticed him, and whether he understood crypto investments were “risky.” Julliard said yes to both, encouraging Cohen to further press him on whether he really bet on FTX thanks to, say, a Formula One sponsorship. The individual ads did not on their own make or break his “decision,” Julliard responded.

A few of the defense’s attempted questions around Julliard’s own practices around commodities were struck by the judge, perhaps barring SBF lawyer Mark Cohen and his colleagues from expanding upon the point they’d made in their opening arguments: that SBF’s behavior was appropriate for his business. Was Bankman-Fried involved with both FTX and Alameda until the end? Why, yes—but look, even when he ceded the Alameda CEO position to Caroline Ellison and Sam Trabucco, he remained majority owner of Alameda, so it was only fair that he remain involved with the hedge fund. Were there transactions between the two firms? Of course, because Alameda had initially served as a market maker for FTX in its startup days, and was able to access bank accounts FTX could not initially access. And look, SBF couldn’t possibly keep track of everything, forget about that whole uber-genius shtick.

Obviously, it’s too early to tell what the jury will make of all this. It’s a pretty diverse crew out there in the box: a South Asian American pediatric nurse, two women who work at different NYC schools, a skinny older white guy in glasses, and a MetroNorth train conductor, among others. They all seemed quite attentive and concerned as the trial’s stakes were laid out, and as various buzzwords of the cryptocurrency industry were explained to them. Prosecutors even asked the witnesses to define what a “cryptocurrency” actually is.

Meanwhile, the media circus spins on. As I left the proceedings and chatted with a fellow observer on the court’s back steps, a camerawoman came up to me and asked if I was Adam Yedidia. Don’t worry—he’ll probably be back tomorrow.