Mick Mars Goes to War With Mötley Crüe

MICK MARS HAS SPENT a great deal of time thinking about his own death, which will happen, he estimates, in about eight years, tops. There won’t be a funeral or memorial service of any kind. Instead, the Mötley Crüe guitarist wants the cremated remains of his body — which has been ravaged for nearly 60 years by the disfiguring bone disease ankylosing spondylitis — packed into a lead urn. “I want them to take it into an airplane and drop it into the center of the Bermuda Triangle,” he says. “I want people to be able to say, ‘Mick Mars is lost in the Bermuda Triangle.’”

It’s a morbid conversation any time, but today happens to be Mars’ 72nd birthday. He’s seated on a couch in the living room of his Tennessee mansion, draped head to toe in black, with his thin black hair protruding from the back of a newsboy cap. His skin is so pale it looks almost translucent. About five feet away are 10 enormous Marshall speaker stacks and studio-quality microphones that he’s been using to record his debut solo album. “I don’t feel a day over 71,” he jokes as I greet him.

More from Rolling Stone

Hear Dolly Parton Scream for Vengeance With Judas Priest's Rob Halford

Motley Crue Refute Mick Mars Lawsuit Claims As 'Unfortunate and Completely Off-Base'

His phone has been buzzing all day with birthday wishes from family and friends, but he hasn’t heard a word from his three bandmates. Mötley Crüe are in the midst of a nasty legal battle following Mars’ decision in October to retire from the road after spending last summer on a reunion tour alongside Poison, Def Leppard, and Joan Jett. Mars has alleged in court filings that the band used this as an excuse to remove him from the group he co-founded 42 years ago, denying him what he sees as his share of future band proceeds. In the legal proceedings, he’s also accused his bandmates of miming to prerecorded tracks on the tour, and they’ve turned around and said Mars was the one faking it onstage, since, they say, he was unable to remember the songs or play them properly. The case has just started to work its way through the legal system, and emotions remain hot.

“When they wanted to get high and fuck everything up, I covered for them,” Mars fumes. “Now they’re trying to take my legacy away, my part of Mötley Crüe, my ownership of the name, the brand. How can you fire Mr. Heinz from Heinz ketchup? He owns it. Frank Sinatra’s or Jimi Hendrix’s legacy goes on forever, and their heirs continue to profit from it. They’re trying to take that away from me. I’m not going to let them.”

Speaking a few weeks before the start of Mötley Crüe’s European tour with replacement guitarist John 5, bassist Nikki Sixx — who has largely stayed silent alongside the other members — vents months of pent-up frustration. “We’re sitting there, coming back from retirement, and our guitar player can’t remember songs,” he says. “We were there watching him physically fall apart, mentally fall apart, his memory fell apart. We really were, with kid gloves, always trying to support Mick. We’ve always stood by his side. But we couldn’t let his side of the stage just be a train wreck. And now he’s only saying these things because he’s trying to hurt us. What’s the point? He’s destroying his own legacy.”

On the morning of his birthday, Mars is just trying to focus on the day’s plans. His wife, Seraina, bought him a Roland System 8 synthesizer as a present (“It does lots of cool stuff!” Mars says, excitedly), and she’s been up since 5 a.m. roasting a pork butt in the backyard’s Big Green Egg barbecue. An ornate, enormous chocolate cake with white-pearl sprinkles — made from scratch — sits in the fridge. Their long-haired Maine coon cat, Ernie Ball, lounges on the couch while an ad for the TruTV show Ghost Hunters plays on the television. There are plastic skulls of all shapes and sizes stocked throughout the house, including a skull cup in the kitchen that holds packets of Equal and Sweet’N Low. Two long, wooden skulls hold up the subwoofer in their home theater.

This may sound weird and gothic, but it’s actually a very warm and homey environment compared with Mars’ past. Back in the Eighties, Mars spent his nights driving his Corvette around Los Angeles and getting plastered at Sunset Strip bars. But nowadays, he rarely leaves his home, preferring to curl up on a brown leather recliner with Seraina to watch horror movies in their screening room. “All the Hostel movies are good,” he says. “But I prefer the older horror movies. Some of them are so bad they’re good. The new ones are like polished, overproduced records.”

L.A. GLAM : Mars, Sixx, Neil, and Lee

It’s a strange thing to hear coming from the guitarist who co-wrote “Girls, Girls, Girls” and “Don’t Go Away Mad (Just Go Away),” not exactly minimalist, unpolished productions. But Mars was never a perfect fit for an Eighties glam-metal band. He’s a decade older than his three bandmates, and had way more love for blues-rock bands like Ten Years After and Bad Company than the glittery groups like Kiss and the New York Dolls that the others worshiped. “There was a lot of really good stuff in the Seventies,” Mars says. “I wish I could have [been successful] then. I would have been a better fit. But I missed that boat.”

He wouldn’t catch that boat until he was 29. Broke and desperate with three young kids to support, he met his Mötley Crüe bandmates through an ad billing himself as a “loud, rude, and aggressive guitar player.” Within months, they were the hottest band on the scene thanks to an explosive stage show, tight leather outfits, and liberal usage of hairspray, mascara, and lipstick. “I went along with the makeup, but I never liked it,” he says, sighing. “I looked like a really ugly old woman.”

MICK MARS DOESN’T REMEMBER when the pain began, but he thinks he was about 14 or so. It started with sharp aches at the top of his tailbone. By the time he began gigging around L.A. in club bands a few years later, it started to spread throughout his body. “I remember telling a friend that my back was hurting so bad that it felt like I had a hole in my stomach and stomach acid was burning my insides,” he says. “I grabbed a hold of a doorknob and said, ‘Pull on me as hard as you can.’ But my back wouldn’t crack, and the pain kept getting worse. My whole body started to bend. It made me look older than I already was.”

When he was 27, a doctor diagnosed him with ankylosing spondylitis. “I thought, ‘Cool, I know how I’m going to die now,’” he says. “But it isn’t AS that kills you. It causes something else to happen that kills you. It rarely goes into your hands or feet. That meant I could play guitar, and that’s what mattered most.”

For the man born Robert Alan Deal in Terre Haute, Indiana, playing the guitar “mattered most” ever since he was three years old and watched country singer Skeeter Bond play a 4-H Fair while standing on two picnic tables. “He was wearing a bright-orange outfit with rhinestones all over the place, and a big white Stetson hat,” says Mars. “I went, ‘I’m doing that. That’s what I want to do.’”

“They’re trying to take my legacy away, my part of Mötley Crüe, my ownership of the name, the brand. How can you fire Mr. Heinz from Heinz ketchup?”

When he was nine, his family of seven squeezed into their 1959 Ford Galaxie and drove more than 2,000 miles to the working-class town of Garden Grove, California. Money was painfully tight, and would remain so for Mars until the Crüe took off in the Eighties. But his parents saved up enough to buy him a guitar, and he practiced relentlessly, thinking of little else beyond making it big. His life shifted, though, when his girlfriend Sharon gave birth to their son Les Paul when he was just 19. A daughter, Stormy, followed a couple of years later.

He spent his days operating heavy machinery in an industrial laundromat, and his nights playing tiny clubs with his band Wahtoshi. When a workplace accident nearly pulverized one of his hands and he quit to focus full time on music, Sharon walked out and took Les and Stormy with her. It began a difficult period for the broke, fledgling musician that involved playing in third-rate bands around L.A., crashing on couches and floors, and dodging cops demanding overdue child support.

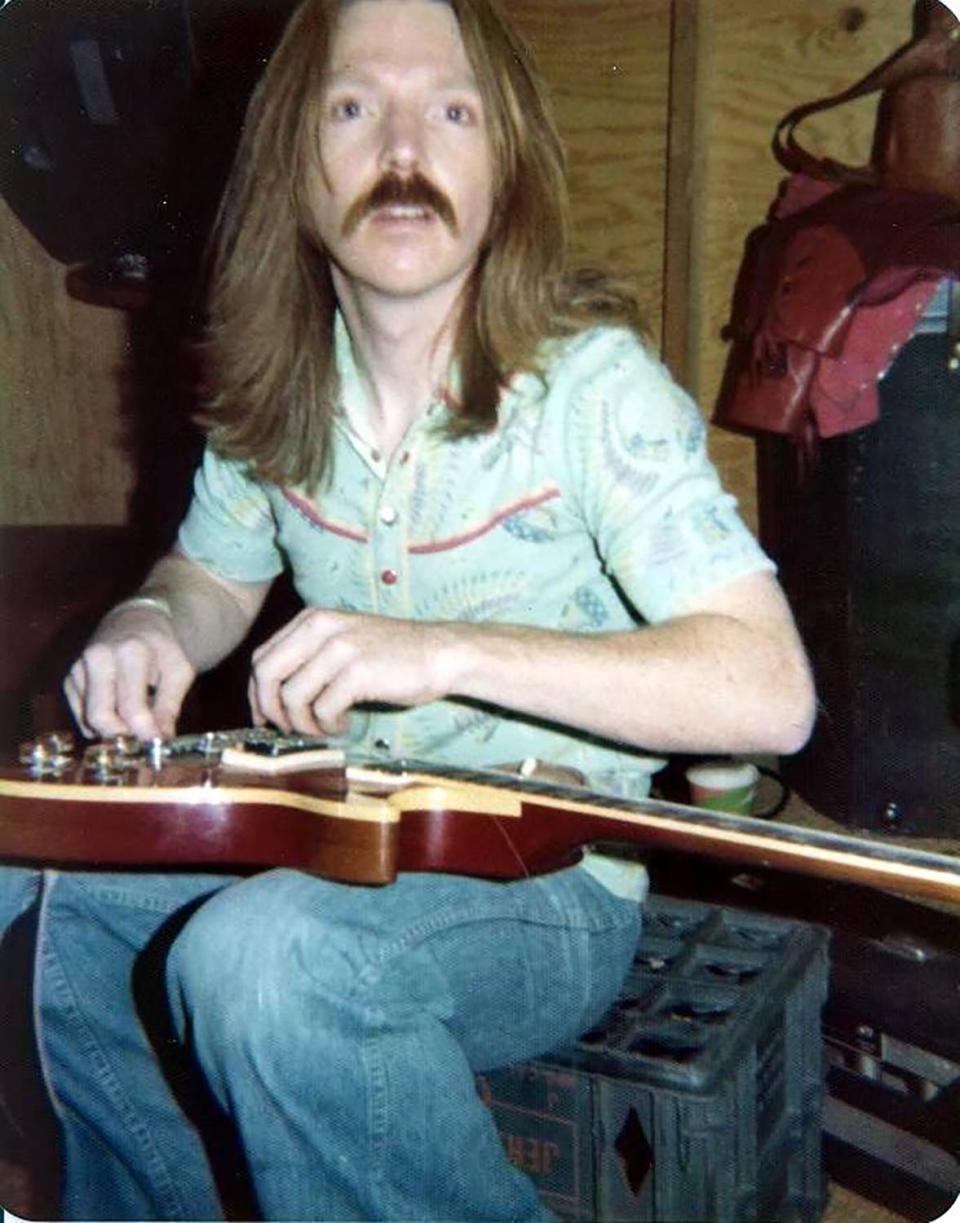

In 1973, he joined the moderately successful cover band White Horse. “He had very good intonation,” recalls White Horse bassist Harry Clay. “And a very good ear and timing. He could copy parts note for note. You give him [Deep Purple’s] ‘Highway Star,’ and he could nail Ritchie Blackmore’s riffs.”

But even with a steady paycheck from White Horse, Mars still couldn’t afford his own place and had to crash on the floor of an apartment Clay shared with White Horse drummer Jack Valentine. He conceived his third child, Erik, on that floor, making his financial situation even more perilous. “He was a real sad guy,” says Valentine. “Looking into his eyes, I just saw this world of sorrow. He had such a hard life.” (Mars is in touch with Les Paul today, but estranged from his two other kids. His wife of nearly 10 years has never even met them. Mars believes he has nine grandkids and at least one great-grandchild, but he’s not sure of the exact number. It’s not a topic he enjoys discussing.)

“He lived with me for four years and used all sorts of aliases to avoid the police,” Valentine continues. “Any time we got pulled over by the cops for a taillight or whatever, and the cops saw his ID, they’d throw him in jail. We’d have to figure a way to get him out. I had to hock my cymbals once just to bail him out so we could play a gig.”

Mars was worth all the trouble, since he helped White Horse develop a bigger following around Southern California. When Mars joined, their main competitor was Mammoth, another cover band, led by an unknown guitarist named Eddie Van Halen. “Mick Mars and Eddie Van Halen were the two hottest guitar players in L.A.,” says Valentine. “There probably weren’t two better guitar players on the planet.”

But by the late Seventies, many rock clubs on their circuit switched over to disco, and White Horse ultimately pushed Mars out. “You couldn’t play rock anymore,” says Valentine. “Our producer said, ‘If you guys don’t drop this rock & roll crap and get with the disco scene, you’re going to wind up playing beer dives the rest of your life, like Van Halen.’”

EVERYTHING WAS SUPPOSED to be different once Mars teamed up with Sixx and drummer Tommy Lee. He was finally in a band with outsize ambition, chops that matched his own, and a firm commitment to original music. Thinking back to an alternative name that White Horse dreamed up years earlier, he named them Mötley Crüe. (Sixx added the umlauts.)

Mars also found a financial backer to help them cut their first songs, and successfully lobbied for them to fire original singer O’dean Peterson after just a few weeks, feeling he wasn’t quite the right fit. “I remember the first time I saw Vince Neil,” says Mars. “He was maybe 19; this skinny blond kid all decked out in white leather. He looked cool as hell. I was like, ‘I don’t give a shit if that kid can sing or not. Look at the girls! Sex sells.’”

“I went along with the makeup, but I never liked it. I looked like a really ugly old woman.”

Looking back on his Crüe career, Mars says nothing matched the euphoria of that first year, when the band burst out of the club scene and recorded future classics like “Live Wire” and “Too Fast for Love.” The music drew equally from punk, glam, and metal, creating a distinctive, hybrid sound. “That’s when I was the happiest,” he says. “It’s like climbing up the old ladder instead of stagnating in a stinkin’ club. You could feel it and see it. Everything was new. Everyone was like, ‘I haven’t heard stuff like this before.’”

Unlike many metal guitarists of the era, Mars was never showy and disdained shredders. “He had such a great tone,” says John Corabi, who joined the Crüe as a vocalist in 1992 after Neil left the band, and remains close to Mars. “He was into guys with amazing tones like [Mountain’s] Leslie West and Jeff Beck. To Mick, it was about kicking you in the chest and having this ungodly sound. He was a scientist when it came to sound. And he wasn’t just 10 years older than his bandmates, he was 10 years wiser.”

But once MTV embraced them and they started playing to tens of thousands of people a night, things got complicated. His three bandmates dove into the rock & roll lifestyle to absurd degrees, and deep divisions surfaced within the group. When they toured with Ozzy Osbourne in early 1984 — a famously debauched pairing where the Crüe watched the singer drunkenly snort a line of ants (“I saw it myself,” Mars says) — Osbourne bassist Bob Daisley says he wandered onto the Crüe bus one night and saw them discussing a plot to fire Mars. “I said to them, ‘You’ve got a chemistry there, Mick Mars is part of that. Don’t fuck it up,’” Daisley recalled in 2021.

Mars believes the story, though he claims the band never threatened to outright fire him. “They didn’t have the balls,” he says. “But one day at rehearsal they went, ‘[Osbourne guitarist] Jake E. Lee would look good right here.’ I went, ‘I’m the guitar player in the band. Nobody else needs to be there.’” (Sixx says that both of those stories are “100 percent false.”)

Around this same time, heroin entered their scene. “I went, ‘Please don’t ever, ever do smack,’” Mars says. “‘You can’t make music when you’re falling down.’ Well, too late. That really upset me.” Mars admits, though, that he developed a major drinking problem in the Eighties. He had little interest in the groupie scene. “I was the old guy,” he says. “So my groupies had canes.… But look, there’s a time to party your ass off, and there’s a time to stop. You have to go, ‘You know what? I’m done.’”

But even at the peak of the band’s success, Mars was rarely on firm financial footing. “Lumps of cash did come,” he says. “But I was married twice and broke three times. One was before the band formed. Two was the first wife, and three was the second wife. They drained my bank accounts. I lost my house. I lost cars. I lost guitars. I lost everything.”

It’s arguably why he looks back at the Dr. Feelgood era with bitterness, even though it produced five hit singles and catapulted the band to superstardom. “We could have toured that for at least a year and a half,” Mars says. “We did nine months and I was like, ‘No! I’ll just say that somebody was sick in the band.’ When that tour was cut off, I was so disappointed.”

Sixx sounds genuinely baffled by this take. “Nobody in the band got sick,” he says. “We were all clean and sober, and we toured for a long time behind that record until it was probably time to stop touring. These are things that have never been said to us or management. Why would he not share these thoughts with [us] ever?”

According to Mars, if he never brought it up, it was due to his extreme aversion to conflict and absence of any offstage relationship with the band. He says Sixx last visited his house during the Dr. Feelgood era. “He’s only [ever] visited me two or three times at the most,” Mars says. “Tommy came over once, and Vince just came over once, even though he lived around the corner from me in Venice Beach. It’s just the way we worked.”

Sixx, Corabi, Mars, and Lee (from left) in 1994

“THIS IS A SONG I WROTE called ‘Killing Breed,’” Mars says. “It’s about narcissists that keep you pinned down and make you feel crazy.”

We’re sitting in Mars’ makeshift studio right off his living room. Priceless guitars sit in racks and cases all along the walls, including an orange 1960 Gibson Les Paul worth roughly $250,000, and his legendary white Fender Stratocaster, Isabella, that he played onstage at countless Crüe concerts. Much of the paint has peeled off, and it’s coated in dark burn marks thanks to it perpetually being in close proximity to pyro.

The music from his upcoming album, Another Side of Mars, is darker and more aggressive than anything in the Crüe catalog. A quick glance at song titles on a whiteboard in his studio — “Broken on the Inside,” “Alone,” “Lonely in Your Grave,” “Loyal to the Lie,” “Decay,” “Fear,” “Memories,” “Erased” — reveals his bitter frame of mind when penning the lyrics during the band’s meltdown.

Mars refuses to explicitly say if the “narcissists keep you pinned down” quote is a reference to his Mötley Crüe bandmates, but he can’t mask a sly smile. Still, it’s hard to walk through his nearly 12,000-square-foot home and think he’s anything but proud of his Crüe accomplishments. The walls are coated with gold records, vintage Eighties concert posters, and a framed copy of the Oct. 21, 1989, Billboard 200, where Dr. Feelgood sits at Number One.

It was the pinnacle of the band’s success. Grunge hit a couple of years later, Neil quit, and the band tanked when it toured with Corabi to support a dead-on-arrival 1994 album. “We went from arenas to 1,200-seat clubs where you had to walk through the crowd to get to the stage,” says Mars. “I thought we’d made the greatest record we’d ever done. And did I feel cheated? Yes, I did. If we’d done the Dr. Feelgood tour long enough, I wouldn’t have felt cheated.”

They reluctantly reunited with Neil in 1997 to record Generation Swine, and Mars says he was squeezed out of the decision-making process at this point. Corabi, who stuck around for the first few months of the reunion era, backs up Mars’ claims. “They had no respect for Mick,” he says. “Mick was just the grumpy old bastard to them. [Nikki and Tommy gave] Mick shit about his finances and the girls he dated. He’d been dealing with over 20 years of this.”

Generation Swine comes up about 10 different times throughout my two days with Mars, mostly unprompted. It’s a quarter-century in the past, but the trauma still feels fresh and raw. “I don’t think there’s one note that I played,” he says, wincing. “They didn’t want my guitar to sound like a guitar, basically. They wanted it to sound like a synthesizer. I felt so useless. I’d do a part, they’d erase it, and somebody else would come in and play.”

When they went back into the studio to cut New Tattoo a couple of years later, with Randy Castillo on drums in place of Lee, Mars says he was denied a chance to participate. “I didn’t write any of those songs, since I wasn’t invited,” Mars says. “I think I got one lick on that album.” (Sixx disputes this: “Mick played lead guitar, rhythm guitar, and any other guitar that’s on that record,” he says. “And Mick is a guy who wrote some pretty cool riffs, but he’s not a songwriter. And everyone forgets Mick’s health during this time. This is during the period that he had disintegrated into opiate addiction.”)

On 2008’s Saints of Los Angeles, which is the most recent Mötley Crüe record to date, both sides agree that D.J. Ashba handled much of the guitar work, uncredited. Sixx says they had little choice. “Mick was struggling to play his parts,” he says. “So there’s [a] mixture of D.J. and Mick, and we would always make Mick the center focus unless, of course, he couldn’t play his parts or remember his parts.”

The low point came shortly after 9/11, when Mötley Crüe went on extended hiatus and Mars retreated deep into his Malibu home. He was drinking to excess, and the 45 Advil a day he was taking to numb the agony of AS would be replaced by Oxycontin, Vicodin, and eventually near-lethal doses of Lortab. On top of that, a deadly mold had spread throughout his home. Without any tour or recording commitments, Mars rarely ventured outside, and he claims the effects of the mold made him emaciated and delusional.

“I used to see giant reptile aliens at the end of my bed,” he says. “And little hairy aliens. At night, cat people used to come in, the kind my mother used to warn me might come and steal my breath. Luckily, I figured out that I was hallucinating. Other people never do, and wind up jumping out of windows.”

Shortly before the band’s 2005 reunion tour, Mars moved out of the house and underwent hip-replacement surgery. “He moved into my house,” Sixx says. “I took him to doctors, and I actually had to spoon-feed him since he was so fucked up.”

A new, mold-free house and a lucrative tour brought Mars back from the dead, and he managed to have fun in Mötley Crüe for the first time in years. They called the tour Carnival of Sins, giving Mars an excuse to wear the kind of makeup he loves. “I got to slap on some clown makeup and have fun with it,” he says. “I really felt free.”

IN 2007, WHEN THE CRÜE went to Europe to play a handful of metal festivals, Mars met Seraina Schönenberger, a 23-year-old photographer-model-guitarist he chatted with on Myspace a few months earlier. Schönenberger responded to one of his status updates, which led to Mars writing to her directly, something along the lines of “Fuck weekends, they just lead to another week of dread.” The two have been together since.

In 2013, the couple moved from Malibu to the Nashville suburbs in search of a quieter pace and more room. They’ve spent the past year adding a hot tub and a massive nine-and-a-half-foot-deep pool to their enormous backyard, and Schönenberger has overseen every step of the process. Today is chaotic, as a construction team waits to fill up a water tanker truck while Schönenberger seems to be in six places at once. She sprints up the stairs to field questions from the construction crew, comes running when a fuse blows in Mars’ home studio to reset the breaker and all the equipment, continually tends to the pork butt on the grill, and effortlessly carries a chair double her size down a narrow flight of stairs. She affectionately refers to Mick as “Mars Man,” and stops everything the moment she senses he needs anything.

Mars spent a lot of blissful time with Schönenberger after Crüe retired from the road in 2015 following a long “farewell tour.” The band signed a supposed “cessation of touring agreement” contract, claiming it legally prohibited them from playing live again. But they refused to share the document with the press, and it seemed like little more than a cynical ploy to boost ticket sales. Mars swears he believes it was real, pointing to an interview he did in 2014 where he said he’d buy everyone free tickets if they ever toured again. “That’s how confident I was we were done,” he says. “I thought we had a real contract.”

But like nearly every other act that embarks on a farewell tour, Mötley Crüe were full of shit. They returned to the road in 2022, claiming their 2019 Netflix movie, The Dirt, rejuvenated a groundswell of interest they couldn’t ignore. “When the movie came out, I knew what was going to happen next,” Mars says. “I resigned myself to the fact that I had to go on tour again, but I was pretty much done.”

Seven years away from tour buses, airports, and hotels — not to mention his bandmates — was enough to convince Mars that he never wanted to return to the road. Prior to rehearsals, he told the band this was his last tour. “I said, ‘You guys, I’m not retiring,’” Mars says. “‘Do you want to do a Vegas residency or record new music? I’m there. You want to do a one-off? I’m there. I just can’t do the world anymore.’”

His AS had progressed to the point where he was no longer able to move his head from side to side, and he’s permanently hunched over. He’s at least three inches shorter than he was in high school. “My spine is now one solid bone,” he says. “It feels like there’s a 40-pound cinder block tied to my forehead with string at all times, pulling it down.”

He got through every show — he agreed to play only 12 shows, but it stretched to 36 — in a state of near-constant agony. (By this point, his spine had essentially been ground in the shape of a question mark.) But watching videos of himself in that diminished form was somehow even more painful. “I look like a skeleton,” he says. “I hate seeing that on video. But I refuse to use a cane. I refuse to use a wheelchair. If I can’t get up there myself, I’m not doing it. I don’t like the way I look, and I feel very awkward seeing myself onstage like that.”

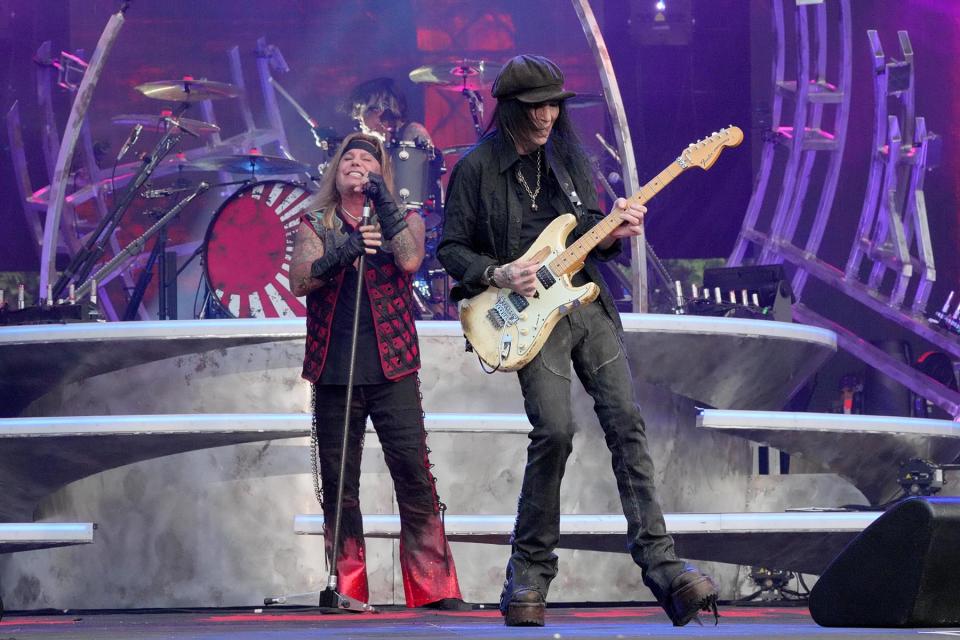

Last Tour: Neil and Mars on tour in Atlanta last year.

THE PRESS RELEASE WENT OUT on Oct. 27, 2022. “While change is never easy, we accept Mick’s decision to retire from the band due to the challenges with his health,” Neil, Lee, and Sixx wrote in a statement. “We will carry out Mick’s wish and continue to tour the world as planned in 2023.” The absence of any Mars quote was suspicious, and fans learned the full story on April 6, 2023, when Mars filed a lawsuit against the band, alleging they had illegally ousted him from the group and cut him out of future profits from all seven of their corporate entities. The 29-page filing is a stunning document, highlighting many of the worst moments in the band’s history and painting Sixx, Lee, and Neil in the most negative light possible.

“Two of the members (not Mars) were addicted to heroin for much of their careers, and one has had a continuous, severe alcohol addiction,” reads a typical passage. “Another band member (not Mars) was placed on probation repeatedly for a series of violent incidents, and was ultimately convicted of felony spousal abuse for repeatedly kicking his wife while she was holding their 7-week old baby.”

“If Mick made these claims in an article or letter, he’d be opened up to liability in a lawsuit,” says Crüe manager Allen Kovac. “But in California, anything in a legal pleading is protected from defamation laws. This just isn’t a real case. It’s a ploy for media attention. If it was a real case, he would’ve made the request in arbitration, and he would’ve gotten these documents anyway because we have nothing to hide.”

The part of Mars’ filing that generated the most attention involved Sixx’s bass playing on the 2022 tour. “[Sixx] did not play a single note on bass during the entire U.S. tour,” it states. “100 percent of Sixx’s bass parts were nothing but recordings.”

The group responded with sworn declarations from seven crew members claiming that Sixx did indeed play live bass, and that Mars often forgot the songs or simply played them incorrectly. Mars doesn’t deny that he sometimes struggled onstage, but has a more nefarious explanation for it. “I was sabotaged musically so they’d have an excuse to get rid of me and bring in another person,” he says. “The feed of guitar into my in-ear monitor was horrible. It would break up, and nobody else’s seemed to break up but mine. And then they’d switch to prerecorded crap from rehearsals, when I was just relearning the songs. They did it to make me look bad.”

“That’s insanity,” Sixx counters. “Why would we do that to our fans? It’s really heartbreaking that Mick and his representatives are lying to the fans while we were trying to protect his legacy. Dude, we love the fuckin’ guy. It’s really scary, [him] being in this complete hallucination. When Mick came into rehearsals, he couldn’t play guitar properly. He just couldn’t pull it off, so we have to use tapes and cover it up. He was the only person in the band on tape.”

The band describes Mars as senile and confused, but I saw very little evidence of this during our time together. There were brief struggles to remember a word or song title, but Mars was sharp, funny, and focused, telling stories from decades past in vivid detail. He moved up and down the many staircases in his home without assistance. He’s certainly frail, and he rarely stood for more than a few minutes at a time, but he seems in complete control of his mental faculties.

Little of this matters, though, when it comes to the major legal question at hand, which comes down to whether or not the band members can unilaterally remove Mars from their LLCs and deny him money. They point to a 2008 band document all parties signed that states that “in no event shall any Resigning Shareholder be entitled to receive any monies attributable to live performances (i.e., tours).”

The Mars camp counters that he’s not a “resigning shareholder,” but merely a member who can’t commit to touring. “If Jeff Bezos decides that he doesn’t want to be an employee of Amazon anymore, he still has his shares,” says Mars attorney Ed McPherson. “Nobody takes that away from him. I don’t understand why these people can think that because Mick doesn’t tour, he doesn’t own his shares.”

“There’s a document that Mick signed,” says Crüe attorney Sasha Frid. “If you’re resigned from touring, you don’t get to participate [in the profits]. You don’t get to sit home in any corporation and collect a paycheck when you’re not out there touring and making your contributions. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

While Mötley Crüe record new songs and tour Europe with John 5 on guitar, Mars is seeking out a record label to release Another Side of Mars, but don’t expect to see him take it on the road. “I’m done touring,” he says. “If somebody really, really wants a one-off, or a couple of nights, I would probably do it. But all that travel stuff and planes … I’m way over it.”

Money is hardly an issue since the 2022 tour grossed $173.5 million, and Mars netted a quarter of the Crüe’s cut. And midway through playing me selections from his solo album, an email arrived in his inbox that put a huge smile on his face. “I sold my publishing!” he excitedly says. “The deal was just finalized. Now I can relax and don’t have to worry about anything, since, like I said, I’m probably just going to live another seven or eight years.”

I wince and say there’s no way he can know this, but he’s adamant. “I’m old enough, man,” he says. “I’m not going to live to be 85 or 90, I just have a feeling. I don’t want to, either. My brain doesn’t want this ugly-ass body that’s all fucked up to keep going. I wish I could just take the information out of my brain, put it on a chip and into somebody else, or a robot. There’s still a lot of stuff going on up there.”

As I pull out of his driveway, a huge water tanker truck pulls up. It’s there to fill up his pool for the first time. His wife was talking about a birthday swim that night. The image makes me smile, and I’m reminded of a last question to Mars: What advice he would give himself in 1981, just as the Crüe were forming?

“Be a little more aggressive,” he says. “Stay out of neutral. Be a voice for yourself. I don’t like conflict, but if I could go back, I’d be more involved.”

I ask if he ever regretted joining the band in the first place. His whole body goes still, his eyes go blank, and I could almost see the band’s entire history spinning through his head — four long decades of success, excess, overdoses, prison sentences, bankruptcies, and the bitter infighting that led to this current legal battle. Eleven seconds slowly tick by before he responds. “Not really,” he says. “We were different when we came out of the Sunset Strip. The rough spots were rough spots, and hard to deal with, but I got to see the world and play with a group that was this successful. So I don’t regret anything … besides Generation Swine.”

Best of Rolling Stone