Justice for Justice League: what is the Snyder Cut, and why does it matter?

What is the Snyder Cut, how much is it worth and who is its wife? For more than two years, these questions and more have been hotly debated by fans, if that’s the word, of 2017’s Justice League – the misbegotten DC superhero team-up that brought on the collapse of an entire cinematic universe.

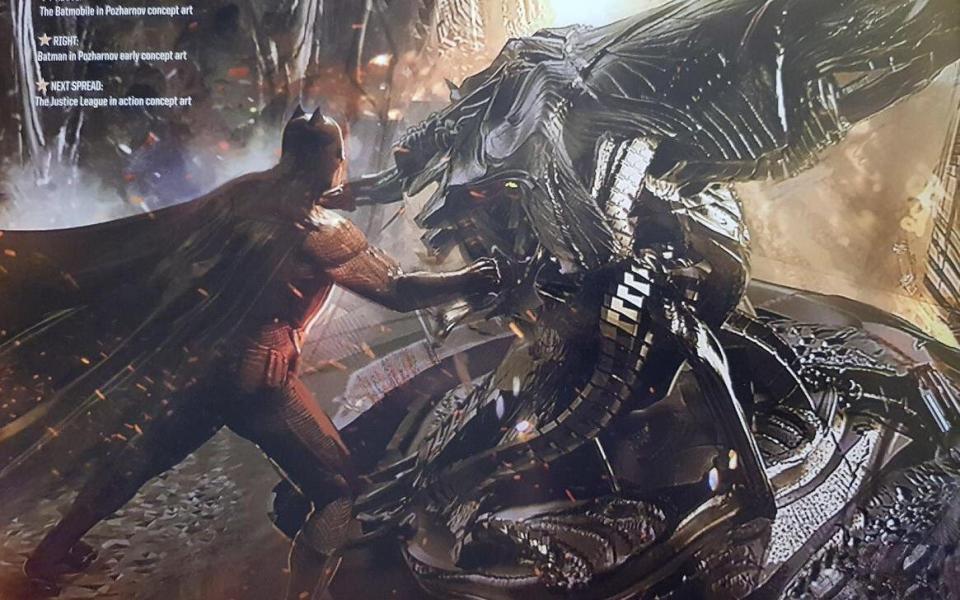

After an unusually troubled production scarred by personal tragedy, spiralling budgets and relentless creative panic, the Justice League that landed in cinemas ended up delighting no-one: not critics, nor Warner Bros’ shareholders, nor general audiences, and least of all the core fanbase who’d bought into its original director Zack Snyder’s divisive and brooding Miltonian vision, only scraps of which were detectable in the theatrical release.

But then the story got out that Snyder had pieced together and screened a four-hour rough cut of the film as he saw it, shortly before leaving the production under the unimaginably painful circumstances of his teenage daughter’s suicide. Rough cuts tend to be nothing more than chunks of unfinished footage lined up in narrative order, with only rudimentary visual effects and a temporary score, if that. But to fans unversed in the post-production terminology, this meant a superior, or at least less artistically compromised, version of the film was out there somewhere, and it was now the studio’s responsibility – nay, duty – to do justice to the Justice League and #ReleaseTheSnyderCut.

And now – to many of us, unbelievably – they will. As my colleague Helen O’Hara correctly surmised last year, a watchable director’s cut of Justice League wasn’t close to existing when Snyder handed the project’s reins to Joss Whedon in mid-2017. But over the next year, at an estimated cost of between $20 and $30 million, Snyder will oversee its completion, and the finished item – either a standalone four-hour epic or a six-part miniseries with multiple cliffhangers – will touch down on Warner Bros’ new streaming platform HBO Max in 2021.

This is an unorthodox move, but also a smart one: the fans who’ve spent the last two years slavering and champing for the Snyder Cut are now basically honour-bound to subscribe to HBO Max and declare the result a visionary masterpiece, come what may. But note that there are examples from history of rebuilt blockbusters becoming just that – or at least a creatively worthwhile exercise in the end.

The version of Blade Runner that’s now often ranked among the greatest films ever made was only completed by Ridley Scott in 2007, 25 years after its first, middlingly received theatrical run. And the more stately, less frivolous Richard Donner Cut of Superman II – a source of succour for Snyder fans during the dark times – was pieced together by Donner, that film’s original director, and editor Michael Thau, in the mid-2000s after sustained fan pestering made Warner Bros realise a second version was commercially viable.

But how different can a Snyder Cut possibly be? Snyder himself described it to the Hollywood Reporter as “an entirely new thing, and, especially talking to those who have seen the released movie, a new experience apart from that movie.” Despite having not seen the original, he estimates a 25 percent overlap between the two versions.

Other estimates are available, however: around the time of its release, producer Charles Roven said that between 80 and 85 percent of Justice League version one was Snyder scenes, though by that point the studio had long adopted the brace position, and were all but pleading with the audience to give the poor blighter a chance.

Yet because the Justice League shoot itself was so tumultuous, it’s possible that both of these numbers are reasonably accurate. Cameras began rolling in April 2016, less than a month after Snyder’s pulverisingly morose Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was received with widespread bewilderment and dismay by critics and audiences alike. The solution handed down from on high was that Justice League had to be lighter and more optimistic in tone – swerving the franchise towards the peppier Marvel house style, and away from the looming, quasi-fascistic imagery and mythic pomp that had been a Snyder trademark for a decade.

As such, the film had begun to fray long before Snyder’s departure. Its screenplay, written by Chris Terrio, was reportedly rejigged throughout the initial six-month shoot by DC stalwart Geoff Johns to bring it in line with Warner Bros’ new vision – which in turn was being informed by consultations with writers including Whedon, Allan Heinberg (Wonder Woman), Andrea Berloff (Straight Outta Compton) and Seth Grahame-Smith (Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter).

As these revisions were slotted into the script, it’s possible that at least some of them superseded scenes that had already been shot, creating the surplus of material required for a four-hour Snyder Cut and around 90 minutes of blander material that formed the backbone of the theatrical version. Of course there’s an easy way to tell which scenes definitely did spring from the Whedon reshoots. They’re the ones in which Henry Cavill’s top lip looks strangely smudgy – a slapdash CG cover-up of the actor’s spectacular moustache, which he grew for Mission: Impossible – Fallout and was contractually forbidden from shaving off.

And this, even for non-fans, is where things could potentially get interesting. Even relatively minor tweaks and additions can drastically alter a film’s tone and even plot – note that in Justice League, both Batman and Superman’s mood-setting introductory scenes both came from the 2017 reshoots – so even if great tracts of Snyder’s version are recognisable, they may play completely differently in a fully Snyderised context.

What’s more, it’s possible that some of that $20-$30 million will be spent on putting the cast into recording booths and taping new dialogue, which with some clever cutting and perhaps the odd CG lip-sync, could be used to completely alter the dramatic function of any given scene. In short, the most intriguing question isn’t how different the Snyder Cut is going to be, but how different it possibly can be – and how seamlessly this promised “entirely new thing” can be constructed from a stripped-down boneshaker and a pile of spare parts.

As for the true believers, here is concrete proof that sustained, impassioned and sometimes toxic direct action can yield serious results, from billboards and banners at ComicCon, to email and social media campaigns, to persistent online harassment of anyone (but usually women) who were deemed not sufficiently supportive of the cause.

In other words, fan entitlement levels, which were hardly low to begin with, are about to skyrocket. Coming soon: an alternative version of Game of Thrones’s final season and the version of Cats with visible CGI anuses under the tails? We can but hope.