James Krauseneck wants Brighton ax trial moved out of Monroe County

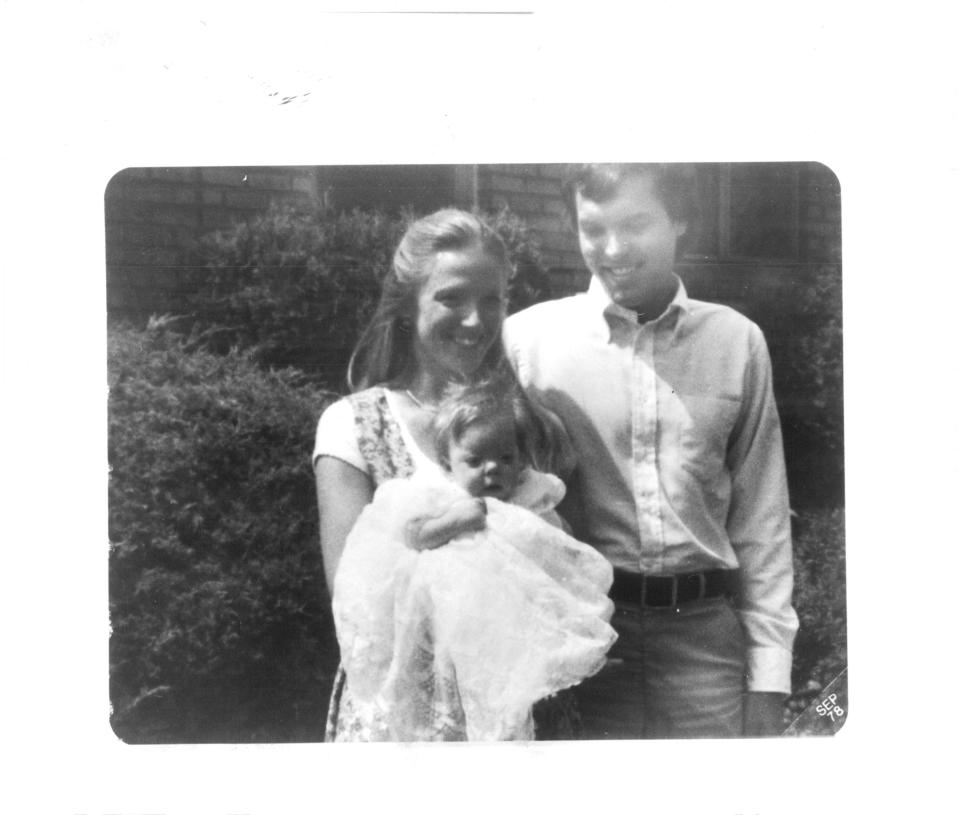

James Krauseneck Jr., accused of killing his wife with an ax blow to the head in 1982, wants his trial moved because of what his attorneys claim is excessive and prejudicial media coverage.

"A fair and impartial trial cannot be held in Monroe County," defense attorney Michael Wolford maintains in court papers filed with the regional appellate court.

Over the past 38 years the media coverage of the Brighton homicide of Cathleen "Cathy" Krauseneck has been of "extraordinary volume" and often portrayed with "a negative tone" toward James Krauseneck Jr., who was indicted in November on a second-degree murder charge, Wolford writes in a legal motion seeking to have the trial moved.

The trial was expected later this year.

Changes of venue with criminal trials are rare, and assistant District Attorney William Gargan, the prosecutor in the Krauseneck case, says in court papers that there is a long history in Monroe County of fair juries selected in high-profile cases.

"Although this case has gained attention in this community, it is no different from other high profile matters that have been successfully tried in this county," Gargan writes in court papers filed with the appellate court on March 13.

In his papers, Gargan points to recent cases, including the trial of four defendants accused of killing Craig Rideout (the accused included his wife and two sons), and the trial of Thomas Johnson Jr., who fatally shot Rochester Police Officer Darryl Pierson.

The sheer presence of extensive media coverage does not ensure that a defendant cannot receive a fair trial, Gargan writes. Instead, he notes with reference to a legal precedent, the defendant must show that the news coverage has "aroused a deep and abiding resentment in the county."

Changes of venue unusual

In his request for a change of venue, Wolford says that the media coverage of the February 1982 homicide has created such intense prejudice against Krauseneck that it warrants the move of the trial to another county.

For instance, Wolford says, much of the media coverage has mentioned how Krauseneck refused to allow his daughter, Sara, to be questioned after the killing. Sara was in the home with her mother's bloodied corpse for much of the day of the homicide, until James Krauseneck returned from his Eastman Kodak Co. job in the late afternoon and found his wife dead.

Sara was then 3½ years old.

Krauseneck also moved back to his Michigan home immediately after the homicide.

Wolford includes articles in his legal motion that he says "cover the investigation's need for Sara's statement and Mr. Krauseneck's refusal to let her be questioned." However, "there is no coverage of how questioning could harm Sara."

"This coverage created a substantial degree of animosity against Mr. Krauseneck," the court papers say.

In a 76-page filing, Wolford includes coverage dating back to the 1982 crime, and stories since the November indictment of Krauseneck. Prosecutors say that new evidence points to Krauseneck's guilt; they allege that he killed his wife before he left for work the morning of Feb. 19, 1982.

Wolford and defense lawyer William Easton, who also represents Krauseneck, say there is no new evidence and they are seeking to have the indictment dismissed.

The coverage that Wolford says has created a bias toward Krauseneck includes news stories from the Democrat and Chronicle.

Getting a jury

Without an attempt to empanel a jury, it can't be known if the media coverage of the ax killing is so expansive that there can't be a fair trial, according to Gargan.

"Extraordinary circumstances" are necessary to decide to move a trial without trying to select a jury, Gargan writes in his court filing.

Instead, he said, New York courts usually wait until a jury pool shows it has been largely impacted by media coverage before they opt to move a trial. Prospective jurors during jury selection are typically asked about the media coverage they have consumed and its impact on their opinions.

Defense lawyers can then ask for a change of venue, Gargan writes.

Appellate courts decide change of venue requests, and it's unclear, with courts now largely closed, when the regional appellate court may rule on the Krauseneck motion.

Last year, in a rare instance, the appellate courts did determine that a criminal trial for former City Court Judge Leticia Astacio, who had earlier been convicted of drunken driving, should be moved.

In that case, Astacio was accused of illegally buying a shotgun in April 2018. Prosecutors alleged that her probation terms prohibited the purchase.

The felony case was moved to Onondaga County and a jury last year acquitted Astacio.

In his change of venue request for Astacio, attorney Mark Foti argued that Astacio had been the target of unrelenting vitriol on social media and talk radio, and that the media coverage had also fostered a bias against her. The appellate judges agreed.

Before the trial, Astacio had been removed as a City Court judge for the drunken driving arrest, subsequent violations of her pretrial and post-conviction release conditions, and incidents on the bench that state judicial misconduct investigators deemed were unprofessional.

Foti said he sees some similarities with the Krauseneck case.

Both cases include extensive media coverage before the indictments: Astacio's actions that led to her removal were popular media fodder before her firearms charge, and the Brighton ax killing has long been a topic of news stories.

"One thing that might be similar between Astacio's case and this case is there is a history of reporting that goes back prior to the announcement of charges being filed," Foti said. "In this case, (against Krauseneck) that period of time is actually more extensive."

Foti said that Astacio's case drew such media attention — and social media ire — that "there's certainly distinguishing aspects between my case and the significant majority of homicide cases that are prosecuted in Monroe County."

At the same time, Foti said, Astacio was accused of the lowest level of felony.

"It was an 'E felony,' " he said. "Any time somebody is facing consequences as severe as a murder charge, I think that the (change of venue) motion has to be given that much more weight."

Contact Gary Craig at gcraig@gannett.com or at 585-258-2479. Follow him on Twitter at gcraig1. This coverage is only possible with support from readers. Sign up today for a digital subscription.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Brighton ax murder: James Krauseneck wants trial out of Monroe County