From Iwo Jima to Vietnam, Shorewood native Dickey Chapelle followed Marines into battle

In her eventful 47 years on Earth, Shorewood native Dickey Chapelle saw the World War II battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. She drove for weeks through the rubble and near-starvation of postwar Europe as it began rebuilding. She experienced the darkness of the Cold War, languishing for weeks in a Hungarian prison. She accompanied Algerian guerrillas in their war for independence against France, and Cuban rebels in their struggle to topple the Batista regime. She walked with U.S. Marines and Vietnamese soldiers along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

With her camera and her words, Chapelle helped Americans see and understand the life-and-death struggles in those places — not in a lofty geopolitical sense, but from the perspective of the boot on the ground.

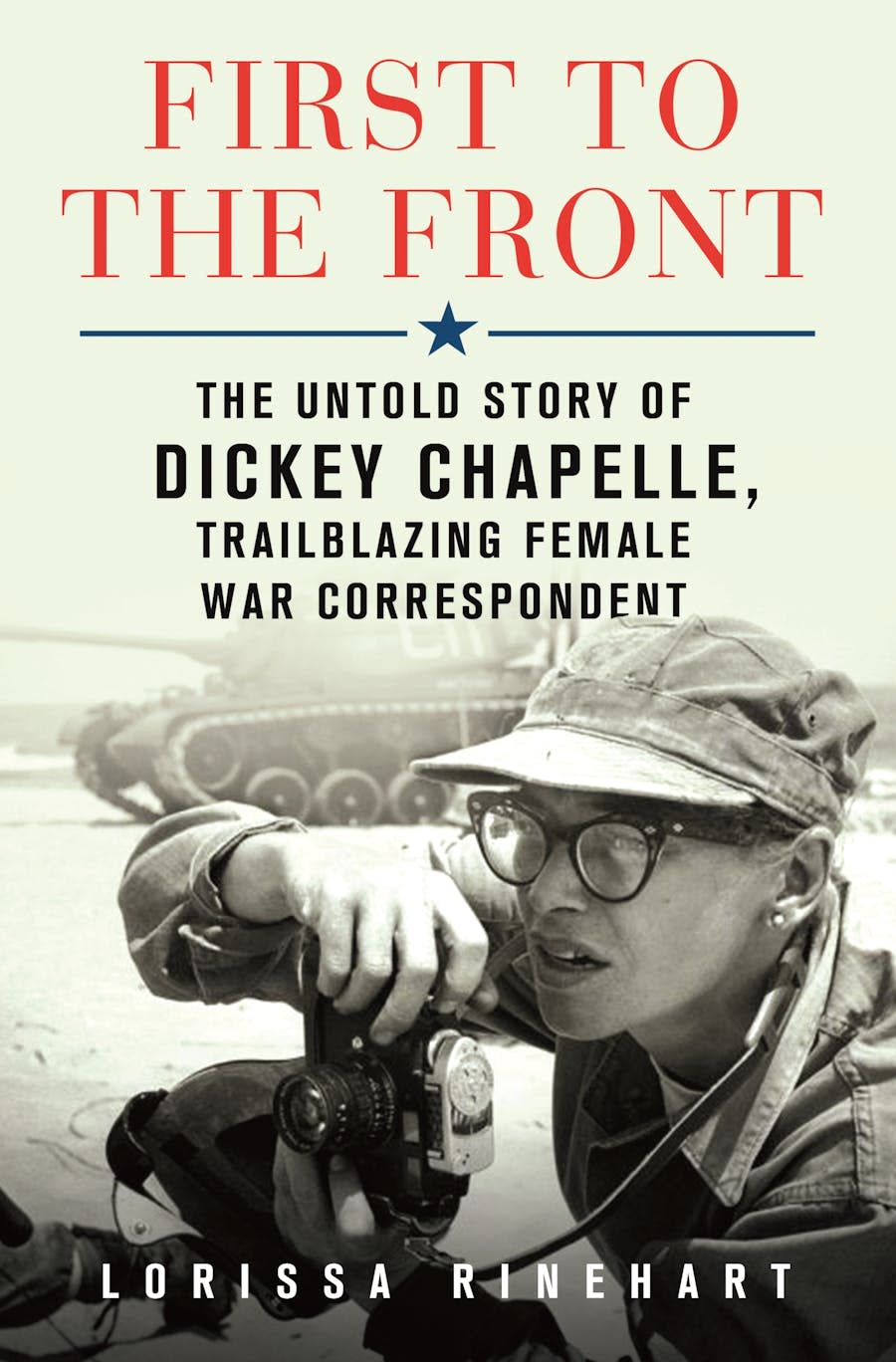

In a compelling and detailed new biography, "First to the Front: The Untold Story of Dickey Chapelle, Trailblazing Female War Correspondent" (St. Martin's Press), Lorissa Rinehart recounts the life of a pioneering journalist who was both of her time and, in some important ways, ahead of it.

On one level, Rinehart's book is a thrilling adventure story, the kind that Reader's Digest, which published much of Chapelle's work, might have excerpted in its heyday. When military commanders in the field would ask Chapelle where she wanted to go, her standard answer was "as far forward as you'll let me." During the fighting at Okinawa, she climbed to the highest point she could reach on a ship to photograph incoming Japanese pilots as they were struck by Allied fire.

Covering anti-locust remediation in the Iraqi desert, Chapelle laid down in a field to photograph a crop-duster scant feet overhead spraying vegetation, insects and herself with pesticide (one believed to be safe for humans).

Valedictorian of her Shorewood High School class, Georgette "Dickey" Meyer flunked out of MIT because she was more interested in airplanes and journalism.

While working for TWA as a young publicity assistant, she married her substantially older photography teacher, Tony Chapelle. As she grew in professional stature, he became more controlling and verbally abusive. This woman who would be accepted and beloved by Marines as one of their own was belittled and gaslit by her feckless husband.

Mustering the courage to leave him, she took up jujitsu to build up her sense of strength. Rinehart writes, "Jujitsu's tactic of redirecting an enemy's energy allowed her, at 5-4 and 125 pounds, to punch well above her weight."

Rinehart identifies a surprising influence on this war correspondent: Quakers. Chapelle had a Quaker editor when she worked for Seventeen magazine, and the American Friends Service Committee sent her to Europe to photograph postwar life there. The biographer sees the radical equality of Quaker theology behind Chapelle's efforts to get American military leaders to treat their Vietnamese counterparts more respectfully.

Chapelle's close observation of and empathy with soldiers and Marines led her to write the 1945 article "It Still Hurts to Get Hurt" detailing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) long before the medical world formally defined it. Her weeks in the Hungarian prison, the most harrowing section of Rinehart's book, contributed to Chapelle's own PTSD.

Her specialty was writing about guerrilla warfare

Rinehart writes that Chapelle's "real specialty lay in guerrilla warfare tactics, about which she wrote for some of the world's premier journals, magazines, and newspapers." She was consulted and asked to speak by military and defense leaders multiple times, although they didn't always heed her recommendations.

Parachute journalism is a pejorative phrase today, used to describe dropping out-of-town reporters into a complex local situation. But Chapelle's parachute journalism was a series of remarkable feats and firsts. Sensing its potential value for future reporting, she took airborne training in 1959, making a night tactical parachute jump into a drop zone from an L-20 aircraft — the first woman to accomplish this feat.

During that time, the intrepid reporter caught on to an American military secret that few people knew about.

"She had an on-the-record, first-person source stating that the U.S. government was conducting covert operations in Laos as early as the spring 1959, 47 years before (the operation) became public knowledge," Rinehart writes.

She made many jumps with the Marines. Then, in 1961, Chapelle made nine jumps with the Vietnamese airborne, the first reporter of any gender permitted to do so. They awarded her their wings, which she wore on the left lapel pocket of her fatigues — the right lapel pocket was already occupied by the wings of 101st Airborne.

Chapelle was pro-democracy, anti-communist and pro freedom fighters. When the first antiwar teach-in was held at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she spoke at a counter-teach-in supporting the people of South Vietnam. While embedded with exiled Cuban commandos preparing to strike at Castro, she helped them polish bullets and make napalm bombs, a line that most traditional journalists today would not cross.

If her lifespan were shifted to the present day, perhaps Chapelle would have become a documentarian with a strong point of view rather than a freelancer constantly hustling to sell articles.

Journalists who cover military operations during wartime always grapple with censorship and restrictions. But during the Vietnam years, especially under the Kennedy administration, she came into increasingly sharp conflict with authorities.

She also distrusted the CIA, whose activities she considered antithetical to American freedoms. In a reminder for our time, Rinehart writes, "Through history and experience, Dickey knew attacks against the press were always a prelude to systematic repression."

Chapelle instinctively identified with the individual combatant. After her experience at Okinawa, she would often say, "When I die, I want to be on patrol with the Marines."

In November 1965, on patrol with the First and Third Battalions of the Seventh Marine Regiment in Viet Cong territory, a young Marine marching in front of her tripped an improvised explosive device. Shrapnel from the explosion cut her carotid artery, and she died soon afterward.

The woman who took so many compelling battlefield photographs became the subject of one herself; French journalist Henri Huet photographed a Navy chaplain giving Chapelle last rites.

She was believed to be the first female American journalist killed in battle.

More: Shorewood photographer Dickey Chapelle who died in Vietnam named an honorary Marine

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: 'First to the Front' details life of war correspondent Dickey Chapelle