Hurricane categories are based on wind speed, but the worst damage usually comes from water. Photos show the real damage storms can do at different strengths.

Wind speed determines hurricane categories — not the rain, storm surge, or flooding they can cause.

Category 1 storms can still kill people, destroy homes, and leave lasting damage in their wake.

These photos show the differences between hurricane categories, using memorable storms as examples.

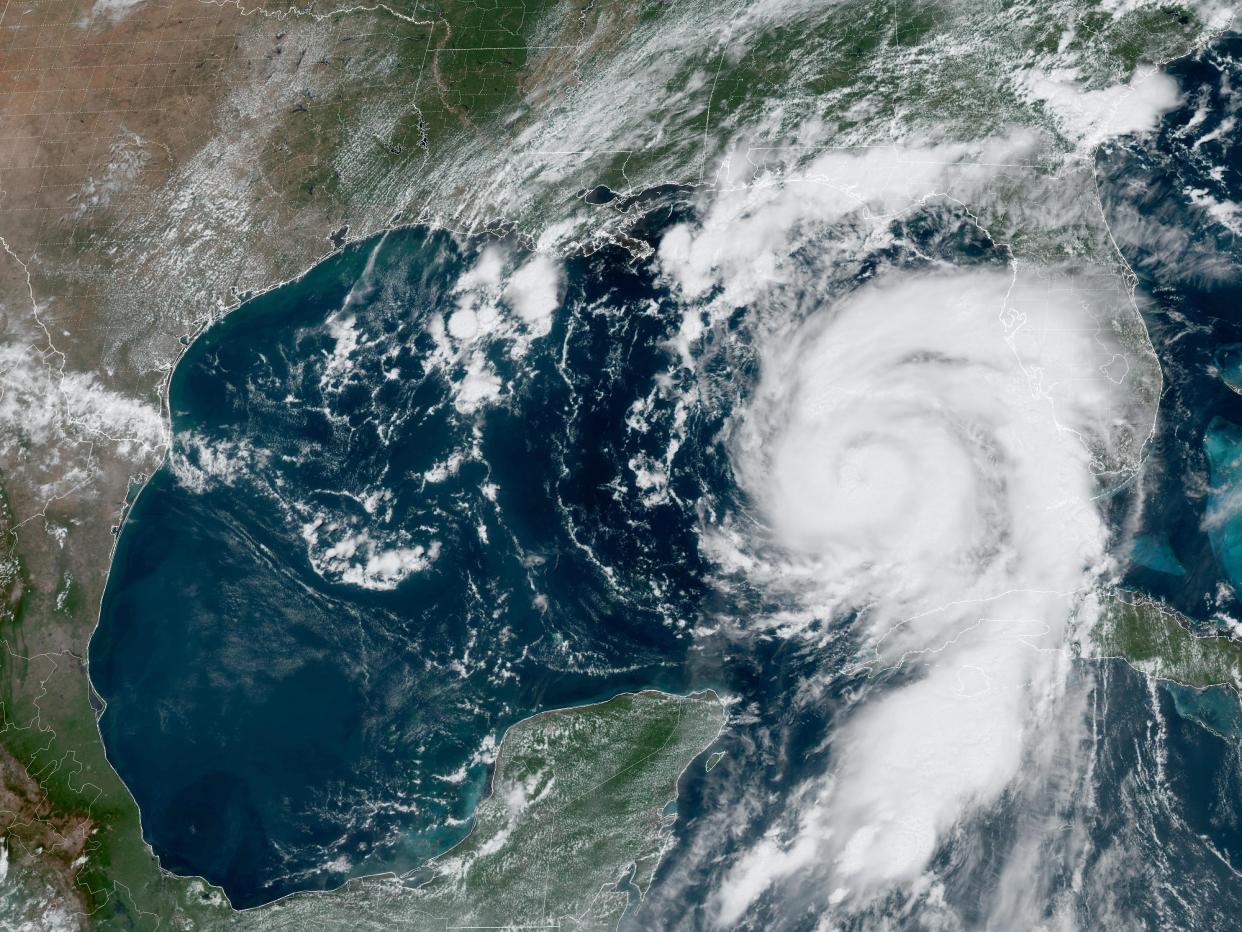

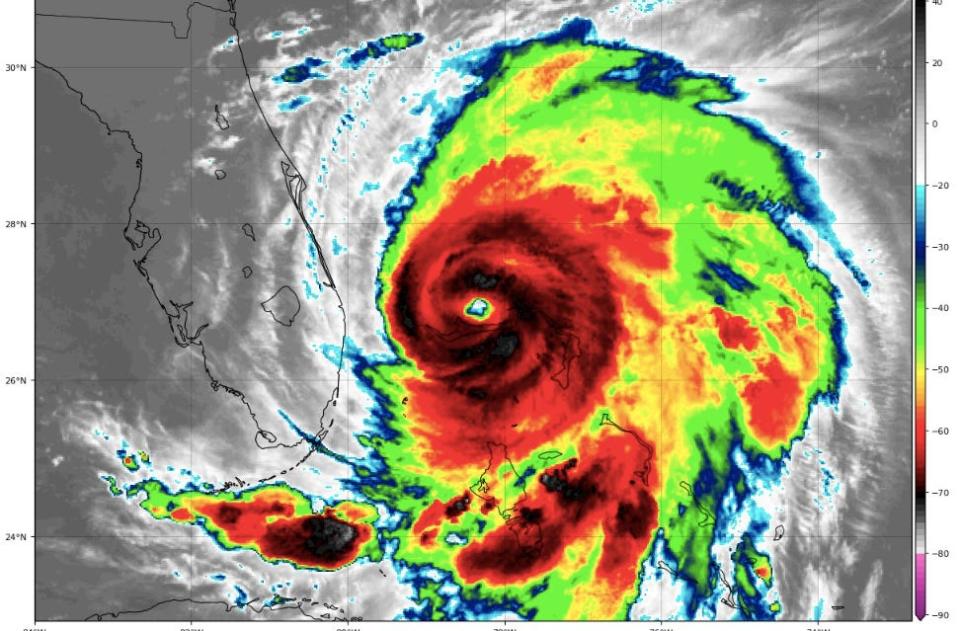

Hurricanes Irma and Harvey were two very different storms.

While Harvey's record rainfall drenched southeastern Texas and western Louisiana in 2017, flooding Houston in over 4 feet of water, Irma's winds flattened buildings, trees, and power lines on the Caribbean islands it devoured.

At its peak, Harvey was a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, but its weakened winds downgraded it to a tropical storm the day after it made landfall.

Irma was a Category 5 monster that was one of the strongest Atlantic hurricanes ever recorded. Both had widespread devastation even though they were on the opposite ends of the category scale.

Hal Needham, a hurricane scientist at Louisiana State University, explained on the weather site WXshift in 2017 that a storm's category doesn't fully convey how much damage it could cause.

"Hurricanes and tropical storms throw three hazards at us: wind, rainfall, and storm surge," he wrote. "Think of the impacts separately. Storms with weaker winds are more likely to stall and dump heavier rainfall. This shocks people, as it would seem intuitive that a Category 5 hurricane would tend to dump more rain than a Category 1 hurricane. But the opposite is true."

Here's a closer look at the type of damage that storms at different categories can cause.

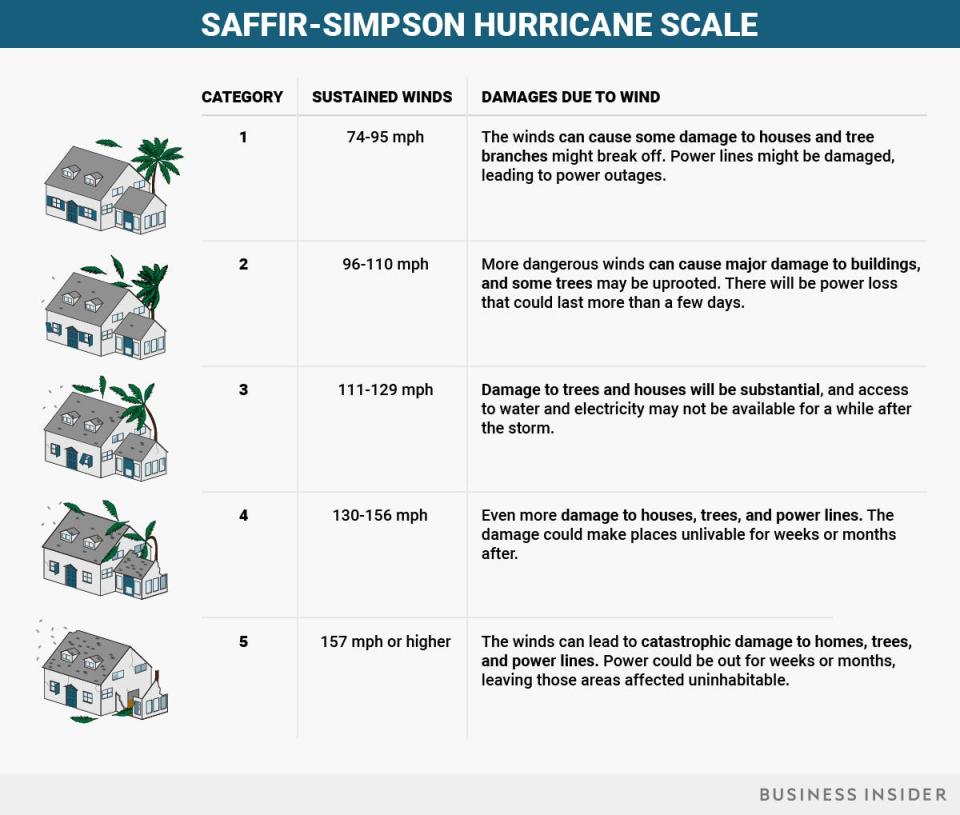

The Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, which does not include lower-level tropical storms or tropical depressions, is based solely on maximum sustained wind.

Source: NHC

Once a tropical storm's winds exceed 39 mph, the storm gets a name.

Most storms that make landfall in the US are tropical storms, not "major" hurricanes of Category 3 and above.

But "storms are too complex to define by one number," Needham wrote.

While Harvey's strong winds on the Texas Gulf Coast caused widespread destruction, most of the devastation came after it was downgraded to a tropical storm, dumping feet of water on Texas and Louisiana.

While strong winds can rip shingles off roofs and tear down power lines, flooding often causes more widespread, costlier damage — and can be more dangerous for humans, no matter what the hurricane category is.

Harvey, for example, was particularly devastating because it stalled over the Houston area, staying in roughly the same place for five days.

Category 1 hurricanes have wind speeds of 74 to 95 mph.

They can damage a home's exterior, break large tree branches, and knock down power lines, causing multi-day power failures.

Hurricane Dorian was a Category 1 when it made landfall in North Carolina in 2019.

When Dorian hit the Bahamas days earlier, it was the second-strongest storm ever recorded in the Atlantic, with 185 mph winds.

The hurricane caused an estimated $3.4 billion in damage to the islands, a report from the Inter-American Development Bank found.

Category 2 hurricanes have wind speeds of 96 to 110 mph.

Storms of this intensity can cause major damage to homes and uproot large trees. They also generate power failures that last up to weeks.

Hurricane Ike was a Category 2 when it hit Texas in 2008.

While a hurricane's category classifies how strong it is, this definition can't fully predict how devastating it might be.

Superstorm Sandy hit as a Category 3, but by the time it made landfall in New York and New Jersey in 2012 it had weakened to a post-tropical cyclone.

Category 3 storms have wind speeds of 111 to 129 mph.

But with Sandy, the storm surge, or rise in sea level, did some of the worst damage. It reached nearly 8 feet in parts of the Jersey Shore and 6 1/2 feet around New York City.

Its "superstorm" status was because it was so wide — up to 1,000 miles across.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was the most devastating storm ever to hit the US.

It killed 1,833 people and caused $108 billion in damage, though Katrina was technically a Category 3 when it made landfall in Louisiana with sustained wind speeds of 125 mph.

Category 4 hurricanes have wind speeds of 130 to 156 mph, uprooting most trees and creating power failures that can last weeks or even months.

Hurricane Charley was a Category 4 when it made landfall in Florida in 2004.

Hurricane Maria was a Category 4 storm when it made landfall in Puerto Rico in 2017, leaving 100% of the island without power.

Parts of the US commonwealth were still recovering from the hurricane two years later — 30,000 homes had tarps for roofs.

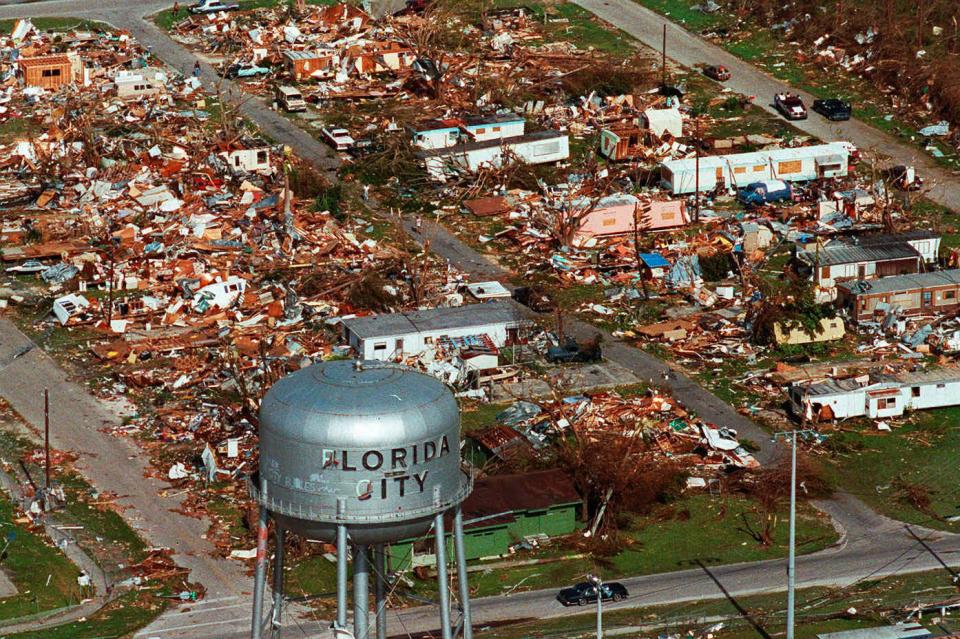

Hurricane Andrew was one of the strongest storms ever to make landfall in the US.

It was a Category 5 hurricane when it hit Florida's Dade County in August 1992.

Category 5 storms have wind speeds greater than 157 mph, which can destroy most framed homes, cause power failures, and leave areas where it hits uninhabitable for weeks or even months.

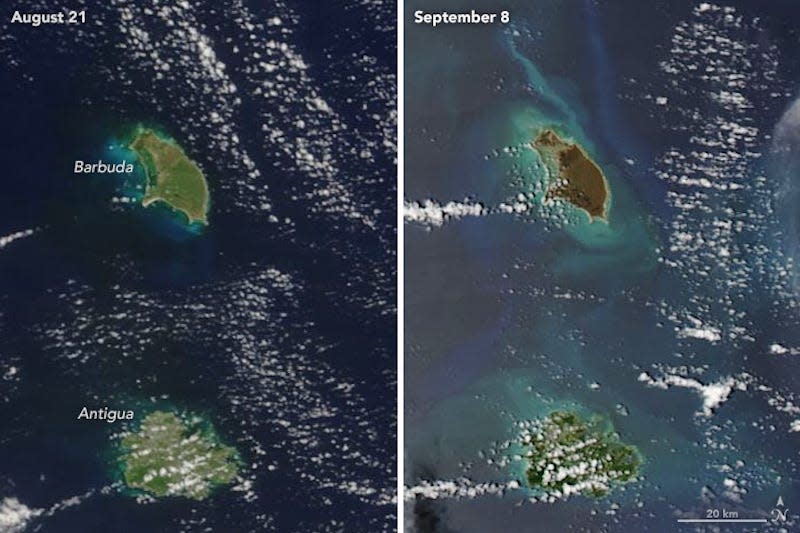

Hurricane Irma was a Category 5 storm when it "totally demolished" the island of Barbuda in 2017.

During Irma, local weather stations in Barbuda captured wind gusts of 155 mph before going silent, indicating that the instruments had been blown away.

The destruction was so severe that the Caribbean island was initially cut off from communication, and 90% of its buildings were destroyed.

Hurricane Irma was so powerful that it could have been considered a Category 6 storm.

Theoretically, if we extended the Saffir-Simpson scale, Irma would be a Category 6, with wind speeds of 175 to 185 mph.

The problem with extending the Saffir-Simpson scale is that it's also a measurement based on destruction, and Category 5 storms typically destroy buildings and utilities.

Technically, hurricanes above Category 5 wouldn't cause more damage because there's no more damage to be done.

Whether it's a tropical storm or a theoretical "Category 6", the impact for people in a hurricane's wake can be devastating.

Part of the issue is that climate change is causing ocean and air temperatures to rise, which is making hurricanes more sluggish, giving them more time to suck up warm water and gain strength.

Read more: Tropical storms and hurricanes are getting stronger, slower, and wetter due to climate change

Read the original article on Business Insider