Gary Tyler, once the youngest person on death row, opens quilt exhibit in Detroit

Gary Tyler once sold a quilt he’d sewn for $90,000. He never saw a cent of that money.

Tyler had made the quilt, which depicted a man riding a bull, to sell at a raffle at the Angola Prison Rodeo. The rodeo was a program organized by the Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as the Angola prison, where Tyler spent nearly 42 years incarcerated for a crime he was wrongfully accused of. He was at one time the youngest person on death row.

Tyler, 65, was released in 2016. Last weekend, the California textile artist opened his first solo exhibit, "We Are the Willing," at the Library Street Collective in Detroit. The exhibit displays Tyler’s quilts, which double as self-portraits. They depict images and scenes from his time in Angola — time spent in solitary and chopping wood as well as screen grabs from CCTV footage and press photographs.

At Library Street on Saturday evening, chatter and laughter grew as people filed in. Tyler took center stage on a panel moderated by curator Allison Glenn and local fiber artist Carole Harris. A hush fell over the room as he walked in, and he looked up quizzically.

“Hello, everyone. I don’t know why you all went quiet — just relax. I’m just checking the mic,” he said, a bright smile on his face.

Laughs broke the silence. Tyler’s warmth set the tone for the rest of the evening as he touched on his time in Angola, how he came to quilting and how art came to be an anchor for his struggle and survival.

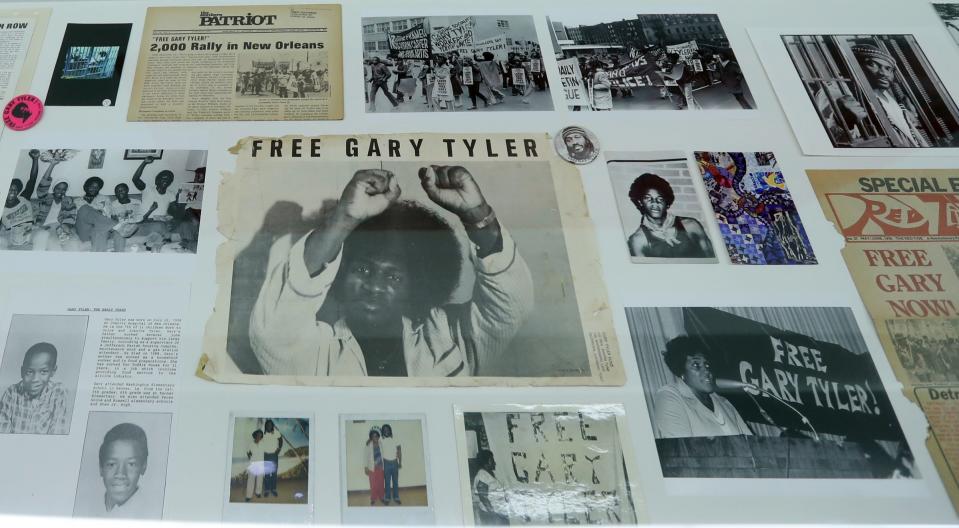

In 1974, Tyler, a 16-year-old high schooler, was riding a school bus in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, which was grappling with conflict surrounding desegregating public schools. The bus was attacked by a mob, and in the ensuing conflict, a white boy was fatally shot. Tyler was charged with the crime as an adult after he turned 17, though a federal court later concluded that his trial was fundamentally unfair.

Tyler’s case received nationwide attention. In Detroit, Rosa Parks campaigned for justice in his case, and in 1976, Tyler's mother arrived in the Motor City to campaign for his release.

“That was one of the best things that happened to my mother because my mother realized that she wasn't the only one that was fighting to free her son and to save her son’s life,” he said. “Detroit had become the hub of the support that I'd gotten. It resonated.”

His mother and the women in Tyler’s family played a crucial role in his discovery of textiles, quilting and art. He recalled how his grandmother stuffed her quilts with rags, old newspapers and moss from the ceiling of their home in St. Charles Parish. Sewing, seen traditionally as a feminine activity, didn’t immediately make sense to Tyler, he said — but it did once he found himself in prison.

At Angola, Tyler began learning the art of making quilts to help out with a hospice program aimed at comforting dying inmates. He remembered the sense of family and comfort quilts had brought him as a boy.

“Guys loved it because they realized what we were doing. They had befriended men that became family to them that were dying in prison.. ... We were making it possible that these men would die in comfort,” he said. “These men’s family would be able to visit them because the money that we was making (from selling quilts) was being utilized to help the guys' families. ... So that itself gave us all comfort knowing that we was doing an admirable thing.”

Butterflies, which Tyler saw as a symbol of transition and evolution, were a consistent motif throughout the time he spent sewing in prison. His words and art were suffused with a sense of hope and optimism that he acquired once he accepted his circumstances and became determined not to capitulate to them.

In the work on display at Library Street, visitors get intimate insight into Tyler’s self-images.

“What really struck me was the way that he was reclaiming this image, you know, all these portraits people had taken of him,” said Glenn. “Sometimes it was a reporter who was covering an appeal, and he's walking out of the courtroom being denied exoneration, denied an appeal, denied a ruling, and he's walking out and someone is covering the story.”

On Saturday, it wasn’t just local art lovers at the exhibit. Older Detroit residents who had worked on Tyler's behalf in the 1970s — people who had picked up his mother at the airport on her Detroit trip or visited him in prison — were also present.

D’Artagnan Collier, local resident and onetime national secretary of the Young Socialists, remembered seeing Tyler in Angola in a very “inhospitable” environment.

“Gary had his hopes up even at that time, and he was also inspired by the campaign for his freedom, not only by us but by other people,” Collier said. “He was hopeful that he was soon to be free and also adamant about his innocence.”

Tyler wouldn’t be freed for decades. But decades inside didn’t shake the resolve of the Tyler who greeted the crowd on Saturday.

“I want you to know, although it took 40 years, don't think those 40 years went to waste because they did not,” he said. “Those 40 years gave me an opportunity to get myself together. I didn't leave prison not knowing myself, but it took 40 years to change the hearts and minds of the ones who were responsible for sending me to prison. Even though they did not have the courage to undo the wrong that they did, their sons and daughters did it for them.”

“We Are the Willing” will be open to the public at the Library Street Collective, 1274 Library Street (Alley) in Detroit through Sept. 6.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Quilter who spent 42 years on death row opens art exhibit in Detroit