Flashback: Remembering Detroit’s last pro football champs – the Michigan Panthers

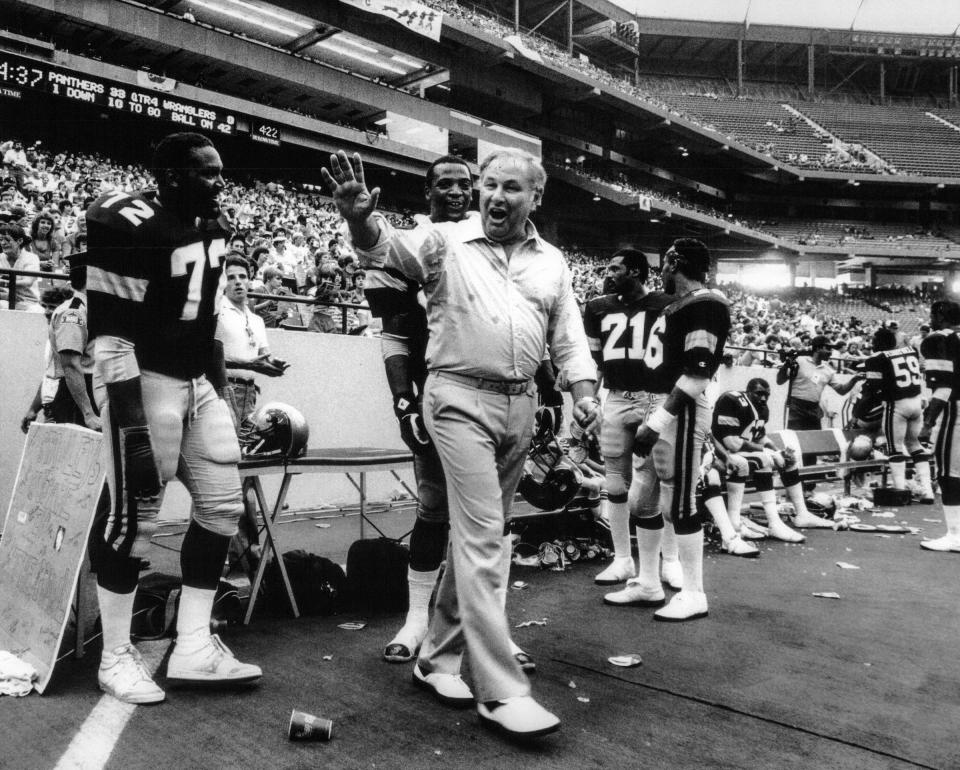

Forty years ago, when the Michigan Panthers won the inaugural championship of the original United States Football League, the celebration began before the game ended. It quickly deteriorated — as did the entire USFL.

In the final minute of a 24-22 Michigan victory over the Philadelphia Stars in Denver’s Mile High Stadium on July 17, 1983, hundreds of celebrants stormed the field. A few of them even joined in the play when Philadelphia scored a touchdown as the clock clicked to “0:00.”

There were no collisions between fans and players. But the Denver police protected the goal posts by spraying Mace, swinging their clubs and siccing their dogs on those who tried to tear them down in the traditional celebration.

Although the game took place at a neutral site, the majority of the 50,000 spectators cheered for Michigan, perhaps in part because the economic recession early in that decade forced many Michiganders to move for jobs to places like Colorado.

In the Free Press, sports columnist Mike Downey described the postgame scene as “revolting and horrifying … vile and violent …”

He wrote: “Young men were blasted in the face by Mace … ‘Pigs! Pigs!’ a girl squealed from the front row …"

The week before, at the semifinal in the Pontiac Silverdome, Michigan fans had taken down the posts. But the mood was different in Denver.

“Dozens of young people were strewn about the grass, their wrists handcuffed behind their backs,” Downey wrote. “Some were wailing and moaning like soldiers in foxholes. Some sat up, crying. There was garbage all about. A ring of cops continued to surround them.”

One Panthers’ star was a Wolverine

Those Panthers and that USFL are only vaguely connected to the current edition of the team and the current USFL, which concluded its season on July 1.

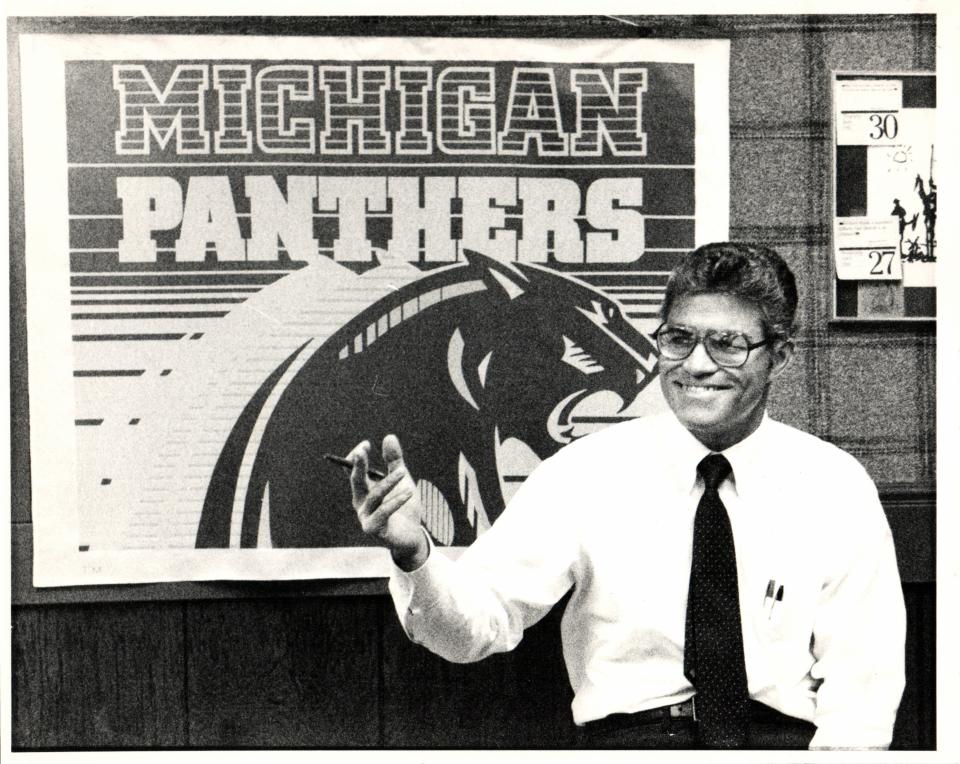

Bankrolled by the shopping mall tycoon Al Taubman, the 1983 Panthers played their spring league games at the Silverdome, then a state-of-the-art home of the NFL’s Detroit Lions and many other attractions.

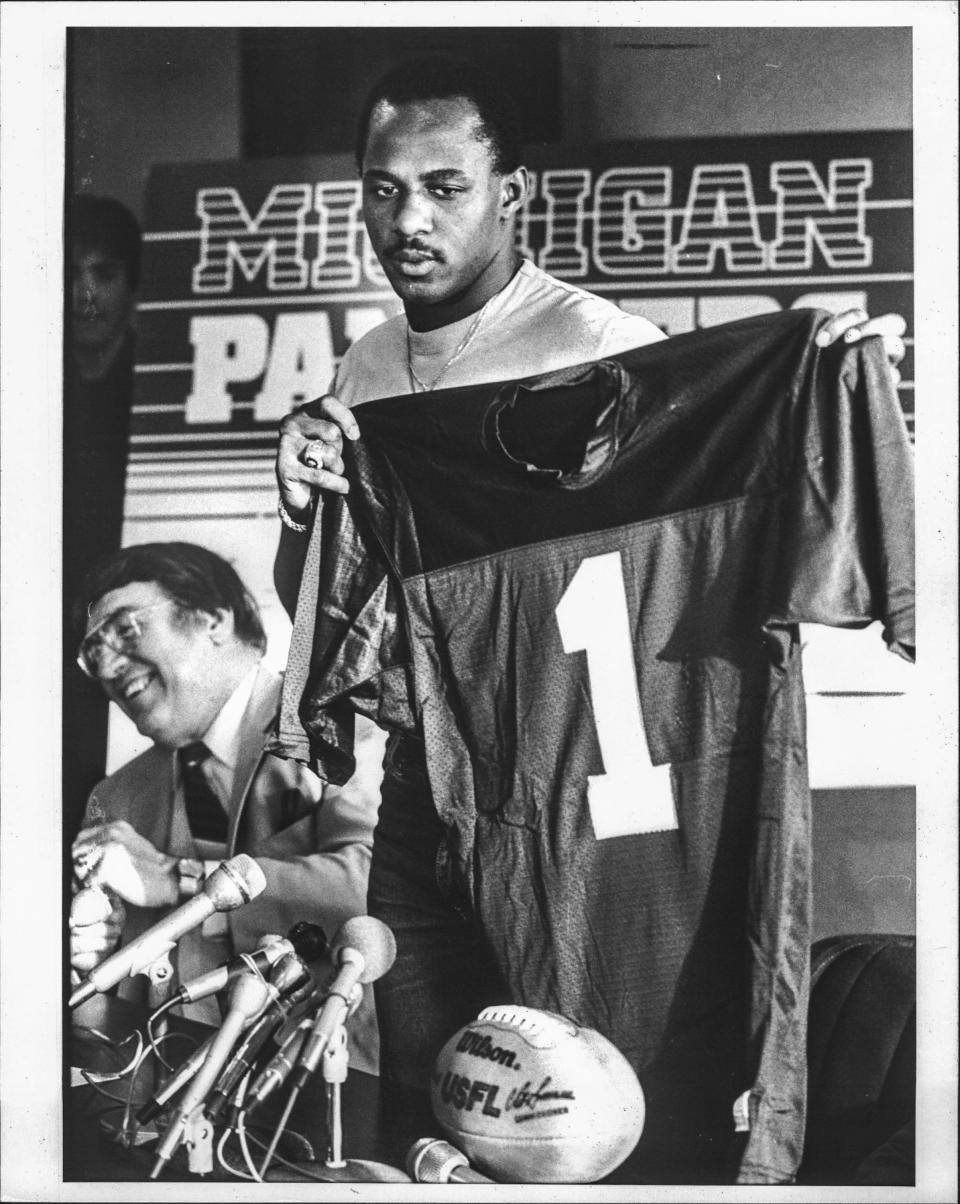

One of the Panthers’ attractions was receiver Anthony Carter, a rookie professional but a star for the previous four seasons in college with the Michigan Wolverines.

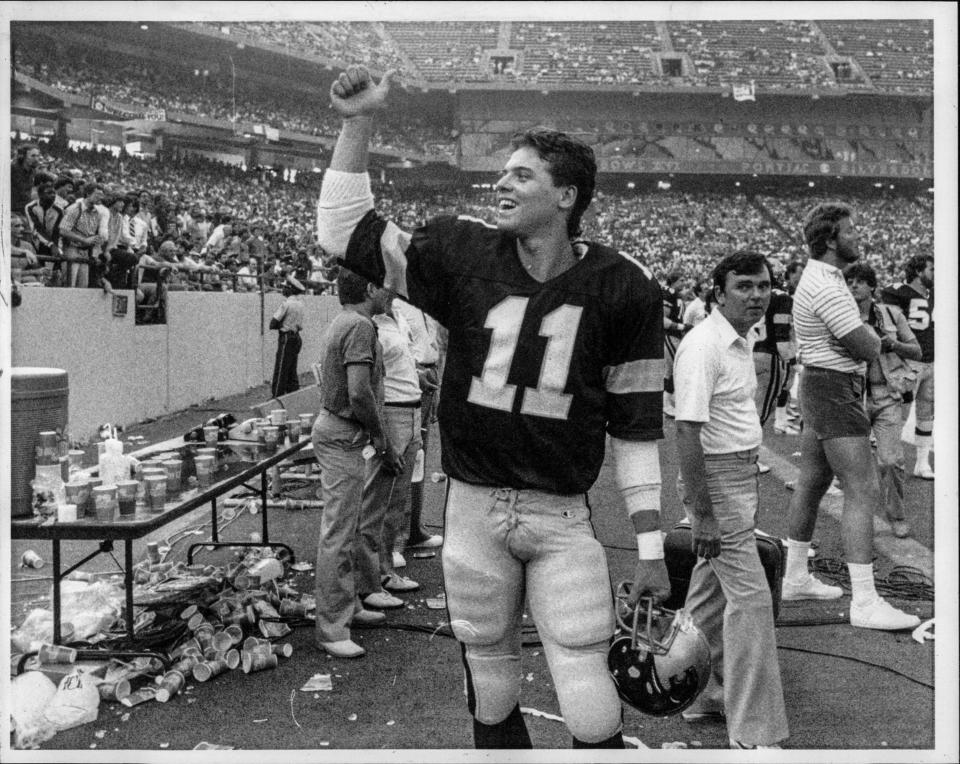

In the title game, Carter grabbed nine passes for 179 yards from quarterback Bobby Hebert, the “Cajun Cannon” from Cutoff, Louisiana, who was the game’s most valuable player with 20 completions in 39 attempts for 309 yards.

The most important — the one that clinched the result — was a 48-yard catch-and-run by Carter, who spun from two tacklers at the 35-yard line and left them horizontal before sprinting into the end zone, kicking his legs and flinging the football into the crowd.

“I should have kept that,” Carter later said.

In that he wore the same numeral “1” on his jersey as in college, Carter declared: “I am No. 1 and the team is No. 1. There’s nothing better than that.”

Those quotations come from the riotously entertaining 2018 book by Jeff Pearlman called “Football for a Buck: The Crazy Rise and Crazier Demise of the USFL.”

Detroit Lions Flashback: Relive day the Lions won their last championship

Flashback: Alex Karras' publicity stunt went awry at Detroit bar

Know-it-all New Yorker butts in

One anecdote involves Vince Lombardi Jr., son of the famous football coach and then president of the Panthers. On a flight to New York, Lombardi met an ambitious, wealthy, young, Big Apple businessman who wanted to invest in football.

The fellow picked Lombardi’s brain about football, then told Lombardi that Lombardi had “no idea” what he (Lombardi) was talking about.

“I thought, ‘Who the hell is THIS guy?’ ” Lombardi said.

Lombardi later learned that “THIS guy” was Donald Trump, who would soon buy into the USFL with the New Jersey Generals as leverage to try to force his way into the NFL.

Rebuffed by the established league, Trump unsuccessfully challenged the NFL with a move from spring to autumn and an anti-trust suit.

“Small potatoes,” Trump famously said in an interview about the USFL.

Both Detroit’s sports landscape and the national political terrain were much different then. The Panthers filled a championship void. The city’s previous major professional sports title had come a distant 15 years earlier, when the Tigers beat St. Louis in the 1968 World Series.

Every stadium is gone

Little remains today of 1983’s local sports venues. The Panthers shared the now-demolished ‘Dome not only with the Lions but also with the Pistons, who played a decade there in a lopsided seating configuration with a big, blue curtain that cut the stadium in half.

That summer, the struggling team hired Chuck Daly, a coach who took them to two championships in their “Bad Boys” era in 1989 and 1990. Their success helped build the new (and now-demolished) Palace of Auburn Hills.

The Tigers, playing in now-demolished Tiger Stadium, were the hot team in town. Under manager Sparky Anderson, they finished 92-70, a year before winning the World Series behind stars like Alan Trammell, Jack Morris and Kirk Gibson.

In that same summer, the Tigers retired the numbers of Hank Greenberg (5) and Charlie Gehringer (2). And entering baseball’s Hall of Fame was George Kell, the TV announcer and former third baseman.

The Red Wings, having recently moved to the then-new (but now-demolished) Joe Louis Arena, finished ’82-’83 with a wretched record of 21-44-15. But under the new ownership of Mike Ilitch, the Wings drafted Steve Yzerman in the first round.

Four Stanley Cup championships later, Yzerman is now the Red Wings' general manager at (relatively new and not-yet-demolished) Little Caesars Arena.

Taubman bows out

Perhaps Detroit’s most-celebrated individual athlete at that time was Thomas Hearns, the boxing champion, who that year held a super-welterweight title. Hearns first fought in Detroit at the (long-demolished) Olympia Stadium.

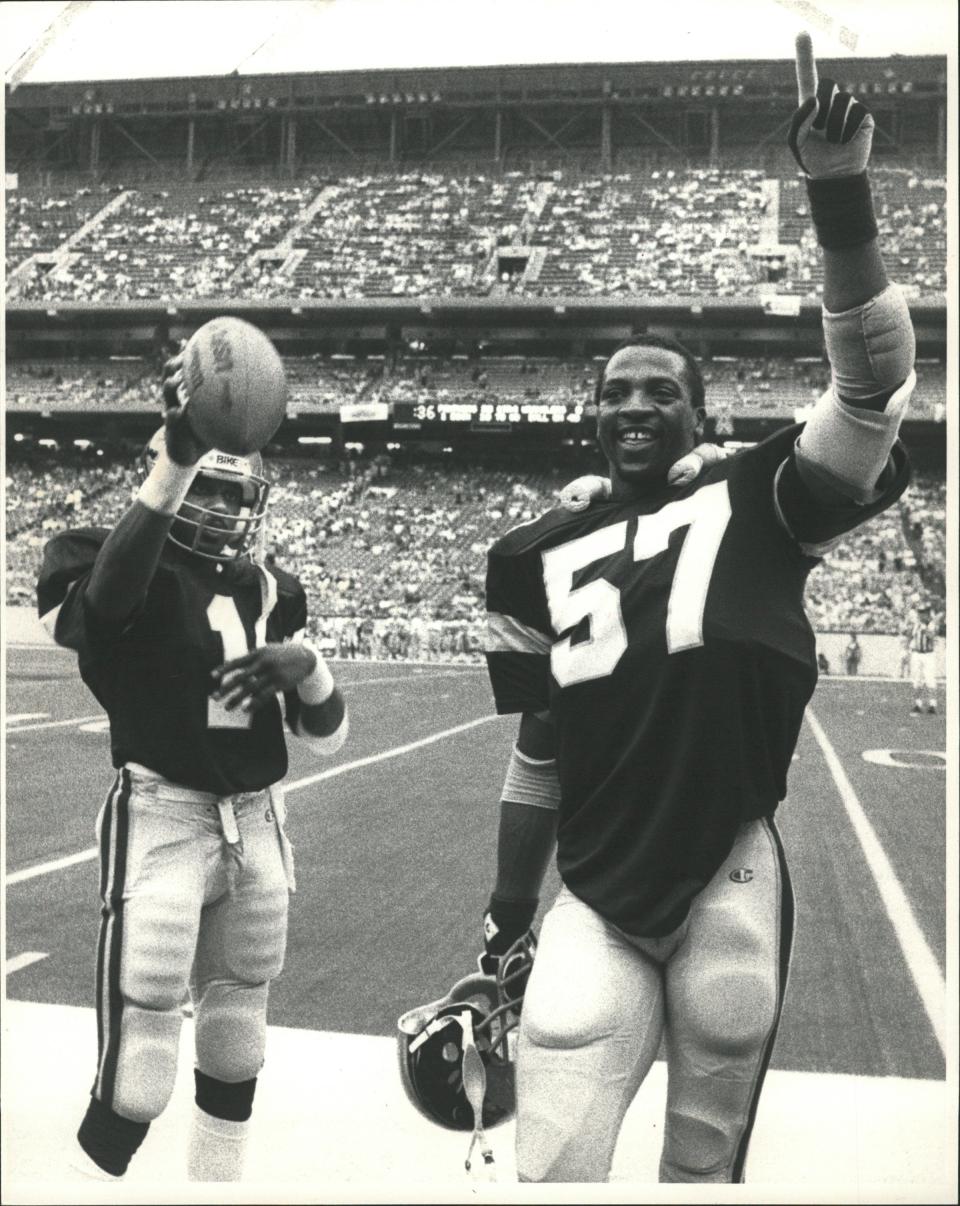

Among the most talented Panthers was the USFL’s most valuable player on defense, John Corker, a linebacker who demolished quarterbacks and registered three sacks in the championship game, which was nationally televised on the ABC network.

Those cameras, however, avoided most of the violence inflicted on all those Michigan fans who ran onto the field.

“It was the USFL’s worst nightmare,” said a reporter for the New York Daily News. “It went from being this great championship game to a riot.”

Who knew then that this mess was a harbinger of bigger messes to come?

A year later, Trump tried to force the league schedule into autumn. With lawyer Roy Cohn, he filed the USFL’s fruitless anti-trust lawsuit against the NFL. (They won $1, trebled to $3).

Taubman, unwilling to compete in the fall against the NFL and Lions’ owner William Clay Ford Jr., sold his Michigan players to Oakland in a merger with the Invaders.

Against those same Invaders in a playoff game in ’83, Taubman had slashed ticket prices and parking fees to help draw 60,275 fans to the ‘Dome. He even let them tear down the goal posts.

One of the league’s best-funded and most visionary owners, Taubman had many reasons to leave the suddenly Trump-centric USFL after its second season in 1984.

“They let people buy into the league that I wouldn’t even let into my box,” Taubman said, according to Pearlman. So the league played a dispirited final spring season in 1985, without Michigan and without hope.

“One of the USFL’s great success stories,” Pearlman wrote of the Panthers. “Now they ceased to exist.”

Joe Lapointe is a metro Detroit freelance writer.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Flashback: Looking back on Detroit’s last pro football champs