Fentanyl, possibly mixed with tranq, still fueling opioid crisis as Summit deaths rise

When an East Akron woman returned home Aug. 7 and found a man passed out on her porch, she knew what to do: Give him a dose of naloxone, the drug that can reverse opioid overdoses, and call 911.

More than 25 people have overdosed and died in her neighborhood — the 44306 ZIP code — since 2022, according to information provided by Summit County public health officials.

The man on her porch, who lives in Kent, survived.

But seven others who overdosed in Summit County between Aug. 4-7 died, prompting public health officials to issue an extraordinarily rare drug warning to a community long rocked by the ongoing opioid crisis.

What made these deaths different, Summit County Public Health Commissioner Donna Skoda said “is they didn’t seem to have any rhyme or reason to them.”

Usually, when there’s a spate of overdose deaths, small groups of drug users or people in the same area overdose together because someone is selling a “hot batch” of drugs, street slang for an unexpectedly potent mix of drugs.

Summit County health officials do not issue warnings about hot batches because some fear that would prompt people with addiction to seek out those especially dangerous drugs.

“I personally think that’s more anecdotal than factual … just because people don’t want to die,” Skoda said. “But addiction is an awful disease and you need more and more and more to keep you satisfied. It’s just so they don’t feel bad.”

Regardless, the overdose deaths that happened between Aug. 4-7 didn’t appear linked to hot batches. People were not only dying in Summit County, she said, but Cuyahoga and Stark counties were seeing similar surges.

It will likely take months for a lab to determine which drugs, or combination of drugs, caused the Summit County deaths.

OD deaths: Where are people are overdosing and dying in Summit County? 7 ZIP codes

And the spate of overdose deaths for now has eased, Skoda said, though it’s not clear if the public health warning made people more careful, or it was something else.

But overdose deaths in Summit County continue to gradually rise during an ongoing opioid crisis that continues to evolve in ways that are sometimes difficult to predict.

Crisis fueled by fentanyl

What started for many with a prescription for the powerful painkiller OxyContin in the late 1990s and 2000s, grew into an addiction and hunt for street OxyContin’s street drug near equivalent, heroin. But heroin, which is made from the seed pods of poppy flowers, is expensive and difficult to import in mass quantities.

Drug dealers soon figured out they could make more money by swapping out heroin for fentanyl, a lab-made synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than heroin.

About 0.002 grams of fentanyl, or 32 grains of salt, can kill a person, according to the Ohio Attorney General’s Office.

But during the July 4 weekend 2016, something even more deadly arrived in Akron — another synthetic opioid, carfentanil, which had historically been used as an elephant tranquilizer.

Less than a salt grain’s worth of carfentanil can be deadly. In just 21 days that July, Akron paramedics logged 236 overdoses, including 14 fatalities suspected to be caused by carfentanil.

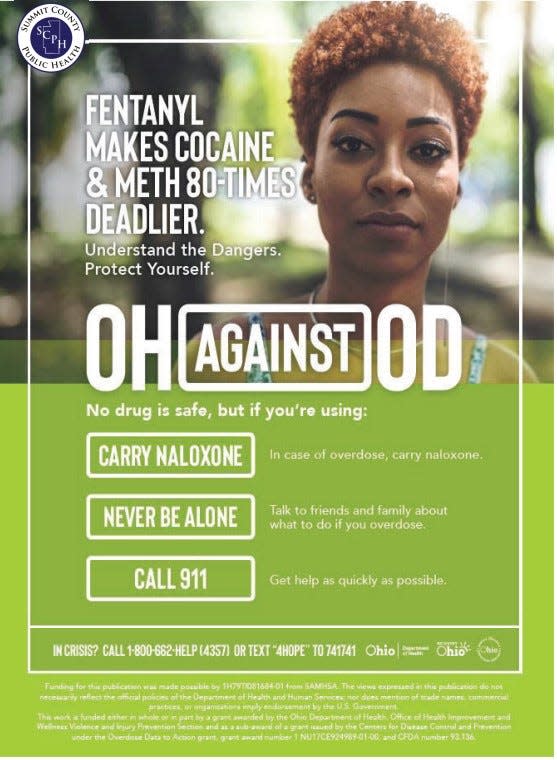

Until 2020, Summit County’s opioid crisis largely ravaged white people, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, overdoses began to rise in the local Black community.

Today, Black users in Summit County are 1.9 times more likely to die from a drug overdose than white users, according to health officials, who have been working with faith and other groups to raise awareness in Black communities.

Overdose deaths rising in Summit

Summit County’s overall overdose deaths, meanwhile, are on the rise, according to Summit County Medical Examiner Dr. Lisa Kohler.

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 11 this year, Summit County logged 123 confirmed overdose deaths and 29 suspected deaths where test results have not yet come in.

White men still make up the overwhelming majority of those 152 deaths: Of those, 71% were white people and 68% were men.

That’s outpacing the number of overdose deaths in the county the past two years, Kohler reported.

For the same time frame in 2022, Summit County logged 139 overdose deaths and ended the year with 247. In 2021, the county saw 146 overdose deaths through August and ended that year with 235, Kohler reported.

About 82% of this year’s overdose deaths involve fentanyl, or a mixture of fentanyl with another drug.

Drugs laced with 'tranq' a new concern

Skoda said two new things worry her about the crisis now: The emergence of the tranquilizer xylazine — called “tranq” or “tranq dope” in street slang – mixed with fentanyl in Summit County, and just how widespread fentanyl is, sometimes mixed with drugs people don’t expect.

Both issues have popped up anecdotally at Summit Safe, a harm reduction program that started in June 2016. The clinic allows users to remain anonymous while receiving sterile syringes, and other supplies like naloxone, along with tests for HIV and Hepatitis C. The program also provides information on recovery, if it’s requested.

People who work in the clinic have noticed an increase in the number of drug users coming in with skin wounds, Skoda said.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) warns that wounds caused by xylazine can develop into necrosis, or the rotting of human flesh, which has also earned xylazine the nickname “zombie drug.”

Xylazine is a drug veterinarians use to sedate horses, cows and other animals. It’s not approved for use with people, yet the DEA has seized xylazine/fentanyl mixtures in 48 of 50 U.S. states.

Drug dealers sometimes mix xylazine into cocaine or fentanyl to enhance a drug’s effects or to increase a drug’s street value, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says.

Xylazine’s more immediate risk, however, is the potential to kill users. Because it is not an opioid, naloxone doesn’t reverse an overdose.

Like fentanyl, xylazine works on the central nervous system, slowing breathing, heart rate and blood pressure, often to dangerously low levels.

If someone is overdosing from a mix of fentanyl and xylazine, naloxone will reverse the fentanyl, but it will not change how xylazine is slowing someone’s breathing, Skoda said.

The CDC advises that rescue breathing — like what you might do during CPR — may be necessary to save the life of a person overdosing on xylazine.

At the same time, Skoda also worries over the vast amount of fentanyl circulating in our area, whether or not it’s mixed with xylazine.

Testing marijuana for fentanyl?

Heroin, Skoda and local drug enforcement officers have said, has nearly disappeared from the streets, replaced entirely by fentanyl.

And fentanyl is making its way into all sorts of street drugs.

Summit County’s harm reduction clinics offer free boxes of strips to test any kind of drugs for fentanyl. They also recently began offering separate strips to test for xylazine.

The strips look and work much like litmus paper used in school labs,.

To use the strips, you break off a tiny piece of whatever drug you’re testing — cocaine, prescription pills (which are often counterfeit on the street), meth — mix the drug with water and dip in a test strip.

The strip will turn color if fentanyl (or xylazine) is likely mixed in the drug. It won't tell you, however, how much of the drug may be present or whether it's a deadly dosage.

Police, public health officials and others have long worried fentanyl could be intentionally or accidentally mixed with marijuana, leaving users who otherwise avoid opioids off-guard and vulnerable.

It’s now apparently worrying some Summit County marijuana users, too. Skoda said people have been coming to the harm reduction clinics specifically seeking test strips for their marijuana.

It’s not clear if fentanyl has made it into any locally sold street marijuana.

But a couple hours after Skoda's interview, she emailed the reporter a story about a Wisconsin man who police said had three pounds of marijuana laced with fentanyl this month.

“This has always been my worry,” Skoda said. “So dangerous.”

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Summit County overdose deaths rising due to fentanyl in many drugs