Doctors and nurses on their risks, fears — and hard decisions — in coronavirus pandemic

Life in the United States and around the world has effectively been put on hold as social distancing has become the strategy of choice against the spread of the coronavirus, which as of Wednesday morning had infected 55,238 and killed 802 in the U.S. Millions are working from home or are out of work entirely, while schools in much of the country are closed.

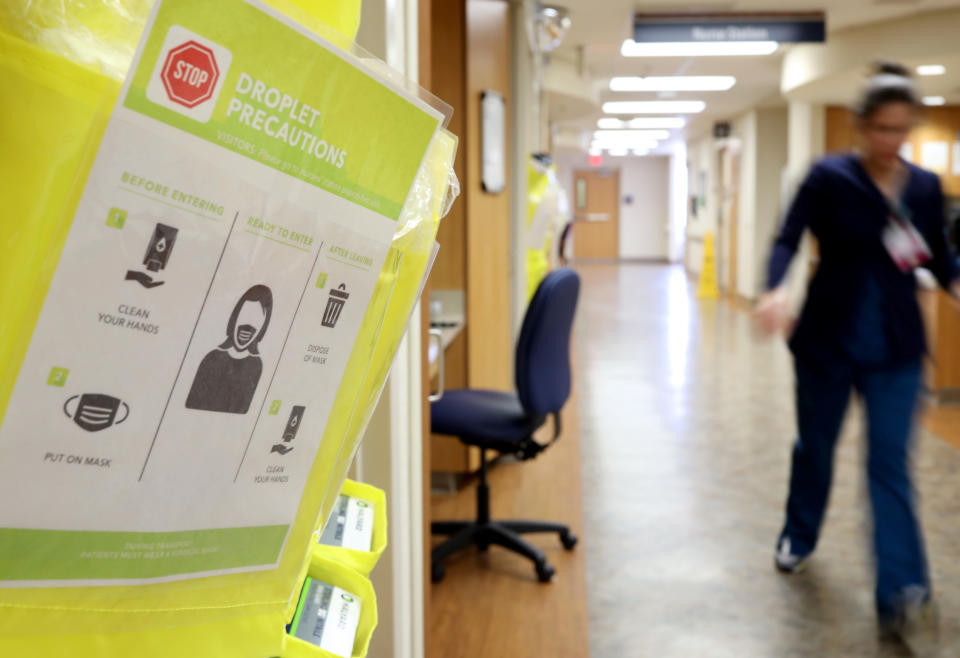

While the general public is being strongly advised to stay indoors, doctors, nurses and other health care providers can’t work from home. They are facing a new reality of their own, as hospitals and clinics prepare for an imminent influx of coronavirus patients.

This is the second in a series of interviews by Yahoo News with health care providers in different parts of the country. This installment looks at the ways the coronavirus pandemic is reaching beyond emergency rooms and frontline medical workers to affect other parts of the health care system. All the providers who spoke to Yahoo News asked that their names and hospitals not be disclosed, because they were not authorized by their employers to speak to the press.

‘We’re forced to go into a situation that we’re recommending the rest of the world not to be in.’

Many hospitals around the country have begun canceling elective procedures in order to free up bed space, equipment and personnel to make room for more likely coronavirus patients. But one surgeon at a large California hospital pointed out that the kinds of procedures that require intensive care are rarely elective, and those can’t simply be canceled even amid a pandemic. The surgeon was not authorized to speak to the press, and asked that his identity, including his specialty, not be disclosed out of concern for his job. However, the types of surgeries he performs are typically emergent, with at least 50 percent or more of his patients requiring recovery time in the intensive care unit, he said.

“You hear on the news that we’re gonna free up all these ICU beds, but that’s really hard to do,” he said. “In an ideal world, we wouldn’t do surgery anymore.” However, there are still “people who don’t have coronavirus [who are] dealing with issues that are life-threatening,” he said, noting that patients continue to be admitted into the ICU with heart failure, strokes and sepsis, among other urgent conditions.

“We can’t say we’re not going to do your surgery because of the potential need [for future coronavirus patients], but every time you do that you’re limiting the number of beds that will be available next week.”

So far the surgeon said he has not been in the position of having to deny a patient a lifesaving procedure to make room for a coronavirus patient, but he worries about that possibility as the number of cases continues to grow. As of Wednesday morning, data from Johns Hopkins University showed that there were 2,628 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in California, including 54 fatalities.

“Eventually, we’ve been told, there’s not going to be enough ventilators and ICU beds, but those beds don’t just appear, right?”

Even as the hospital takes steps to prepare for an impending surge in coronavirus patients, the surgeon expressed shock and concern over what he described as inconsistency between the social distancing measures prescribed for the general public and what is being practiced by health care providers and other hospital staff.

“In the outside world, we’re told to stay 6 feet away from each other and not interact. Then you walk around the hospital and people are having lunch together. You walk into a resident workroom and six people are working on computers, [none of them] wearing masks.

“I don’t know if people have a false sense of security because [they’re] not in the real world, but we know of patients who are asymptomatic,” he said. “In my mind, I think every time you go into a new room you should put on a new mask, but people aren’t doing that.”

The surgeon described what he’s observed as “two worlds” within the hospital: one where certain nurses and doctors, especially anesthesiologists and emergency room personnel, appear to be “wearing masks all day,” and another in which no one is wearing a mask, including housekeeping and cafeteria workers.

CDC recommendations regarding who needs to wear a mask and when continue to evolve along with the coronavirus pandemic — largely shifting in response to supply shortages created by increased demand.

While the surgeon acknowledged that “we don’t have enough resources to treat every single patient like they have the disease,” he worries that failure to take sufficient precautions could result in significant spread of the coronavirus among health care workers.

“We’re screwed,” he said. “We’re forced to go into a situation that we’re recommending the rest of the world not to be in.”

Like other doctors, he worries less about how his own exposure could impact members of his family.

“I don’t let my kids in my own car anymore because I’m worried my car has germs in there,” he said. “It’s impossible not to be exposed to someone sick in the hospital.”

‘If people were to take us as leaders or examples for how to act in this situation, we’re doing a horrible job.’

The surgeon in California is not the only one noticing a disparity between the way health care workers are interacting as opposed to the rest of the public.

“In my personal life, I feel like everyone is isolating, social distancing,” said a nurse in the NICU, the neonatal intensive care unit, at a large hospital in the Midwest. But in the hospital, she said, health care workers are still clustered in halls and eating in communal break rooms, touching elevator buttons and opening doors.

“It feels really hypocritical to be a health care provider and encouraging other people to not do everything that we do as soon as we walk through the doors, said the nurse, who also asked that her name and hospital not be disclosed because she was not authorized to speak to the press. “If people were to take us as leaders or examples for how to act in this situation, we’re doing a horrible job.”

“I was literally dreading going to work because of how much more at risk I felt than in day-to-day life at home,” she said. Even her own efforts to regularly disinfect her personal workspace and any surfaces touched by her patients feel inefficient and wasteful.

“It’s a lot of cleaning up after myself and other people over and over again. That’s not what you should be doing when trying to provide patient care,” she said.

As an NICU nurse, she is not directly treating confirmed or suspected coronavirus patients, but she is being trained to respond to a new patient population emerging from the pandemic: pregnant women who’ve tested positive for COVID-19.

A minimum of three health care providers from the NICU — a nurse, a doctor and a respiratory therapist — are required to attend all high-risk deliveries. Those include cases of fetal distress (such as low heart rate) and any delivery by a mother before her 37th week. Now, she said, deliveries involving a coronavirus-positive mother are also considered high risk.

Between the labor and delivery team and the NICU team, she said there can be up to 20 people present for a high-risk delivery. If the mother has tested positive for the coronavirus, all those people have to be wearing personal protective equipment, which they must each put on according to protocol in a negative pressure isolation room, known as an anteroom, before they enter the delivery room.

Under new visitor restrictions adopted by many hospitals, mothers who haven’t tested positive for the coronavirus are now allowed only one visitor in the delivery room. For those who have been infected with the virus, she said, “I don’t know if those moms are allowed [to have] anyone ... which is so sad. I can’t imagine being a laboring mom alone, with no one in there with you.”

The nurse who spoke to Yahoo News said that her hospital has established a sort of “makeshift COVID labor and delivery floor” with a handful of rooms designated for mothers with the coronavirus to give birth. They’ve started setting up carts of protective equipment outside those rooms; however, at this point only one of them is equipped with a proper anteroom.

“The rest are just regular rooms where we’re saying, ‘Never mind, it’s OK not to have an anteroom. Just put on the PPE outside the door and hope for the best,’” she said, adding that part of her training for this new type of delivery included instructions to “open the door as little as you need to in order to shimmy in and out.”

As with any high-risk delivery, the NICU team’s role is to determine whether the baby appears well enough to go to the regular postpartum floor or if the baby is in distress and needs to be taken to the NICU. For babies born to mothers with COVID-19, she said, the assumption is that the newborn is also positive for the virus, and those that are “well-appearing” upon delivery must be taken to an isolation room on the postpartum floor.

For all the training she’s received on how to handle these new types of deliveries, the nurse said there are still a lot of unanswered questions. Based on what she was told, she said that mothers who’ve tested positive for the coronavirus must remain separated from their baby as long as they’re in the hospital, which, she said, “has a lot of consequences for mental health, feeding, production of breast milk.” But it’s not clear whether, if the baby is ready to be discharged before the mother, who will be able to take the baby home, as the father or partner is also presumed to have been exposed to the coronavirus if they and the mother live together.

“It’s these horrible, heartbreaking situations where we’re talking about finding another family support person to come pick up the baby,” she said.

The NICU nurse said that so far she hasn’t participated in any coronavirus deliveries yet but is already aware of at least one pregnant patient who has tested positive. “It’s very much not a matter of if, just when” it will happen, she said. She worries about how the elaborate, time-consuming process of putting on and removing personal protective equipment and carefully entering and exiting the makeshift COVID delivery rooms will play out in a real-life emergency situation.

“We’re a very well oiled machine, so it’s a very anxious feeling to have so many unknowns in how to provide safe, effective care for people,” she said. “This just feels like chaos.”

‘Every day I go into work thinking, “I don’t want to be that Kirkland nursing home.” That would be the worst-case scenario.’

The impacts of the coronavirus on the health care system stretch beyond the different units of a hospital. The medical director of one mid-Atlantic residential addiction treatment facility told Yahoo News: “Every day I go into work thinking, ‘I don’t want to be that Kirkland nursing home.’ That would be the worst-case scenario.”

The medical director asked that his name and the location of the facility (which includes the state in its name) not be mentioned because it is part of a small addiction treatment community that could easily be traced back to him. But the facility is located in a state that, as of Wednesday morning, had fewer than 400 confirmed cases of the coronavirus.

“We’re not a hospital per se, but we’re a health care facility,” he said, explaining that, unlike at a hospital, the facility’s staff doesn’t have the kind of universal training in infection control practices.

“We give medications and things like that, but we’re not doing very high-level medical care,” he said. “The premise is, if you’re sick you get sent out.”

“Now if you have somebody who has a fever, it’s a major issue,” he said.

The average length of stay at this facility is between 20 and 30 days. They don’t take Medicare or Medicaid, and about 85 percent are covered by private insurance. There are approximately 70 patients and 30 or so staff, he said, so there are about 100 people in the building at a given moment, and it’s a “relatively small space.”

“Up until last week we had a cafeteria in which 50 people easily would be eating, sitting, more or less right next to each other,” he said. The patients would “go from there to various groups with 20-30 patients in a small room.”

Even though patients have TVs in their rooms and have been watching the news about the coronavirus spreading over the past few weeks, the medical director said, “For the longest time I was kind of surprised there wasn’t a whole lot of uproar among patients and staff, up until last week. This last week sort of hit home for a lot of people, I think.”

Several people actually signed out of the facility after a rumor started circulating that the governor was going to enact a shelter-in-place order preventing them from leaving.

“It was a false rumor, but [it was] the kind of thing that has thrown everything up in air,” he said. Since then, the facility has made a variety of changes, including allowing only 10 people to eat in the cafeteria at a time. It has also started working on transitioning some group therapy to a virtual conferencing platform instead of in-person meetings.

Though he said employees are not supposed to come to work if they have any symptoms, there’s been a sense of panic among some of the staff.

“Several staff members who are not young and have chronic medical conditions, asthma, etc., are appropriately concerned about walking around a building with 100 people in petty close proximity,” he said.

While he believes the treatment facility should follow the CDC’s recommendation that anyone confirmed or suspected to have the coronavirus who does not need to be hospitalized should self-quarantine at home, he also noted that determining whether to send a sick patient home from the facility he runs presents a uniquely difficult dilemma.

“One thing we always keep in mind is every decision we make is based on the safety of the patients,” he said. “But in our particular case, a lot of the time people are not safe if they’re not in treatment.”

“If you have an alcoholic with liver disease, which is a frequent type of patient, [and] they go home and start drinking again, they are going to die from alcohol,” he explained. “In the case of patients who’ve been discharged from hospital [who are] still kind of semi-sick, we’ll take them back because the alternative is worse.”

For example, he said a patient was recently sent to the hospital because he was sick, and while he was there, it was discovered that this patient, who is already in the late stages of alcoholic liver disease, is also diabetic.

“He could’ve been admitted, and I think should've been admitted, [but] because of the COVID thing, I think there were not as many beds. [The hospital was] pushing to discharge him,” he said. “I had a choice of saying he’s too medically unstable to come back to us, but in that case he would go home and very likely drink again and become much sicker faster.” He decided to take the patient back to the treatment facility, even though he wasn’t fully medically stable.

The medical director said he’s often put in this type of position in his job. “The only thing that changes it with COVID is, you’re risking other patients’ safety by keeping them there.”

“Ethically, I have a responsibility to my staff and the other patients to keep them as safe as I can, and we also have responsibility to patients who may have COVID,” he said. “There’s a competing ethic there, where that person may be safer in our facility by not drinking or drugging, but they may also [be] causing significant risk to patients and staff.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: