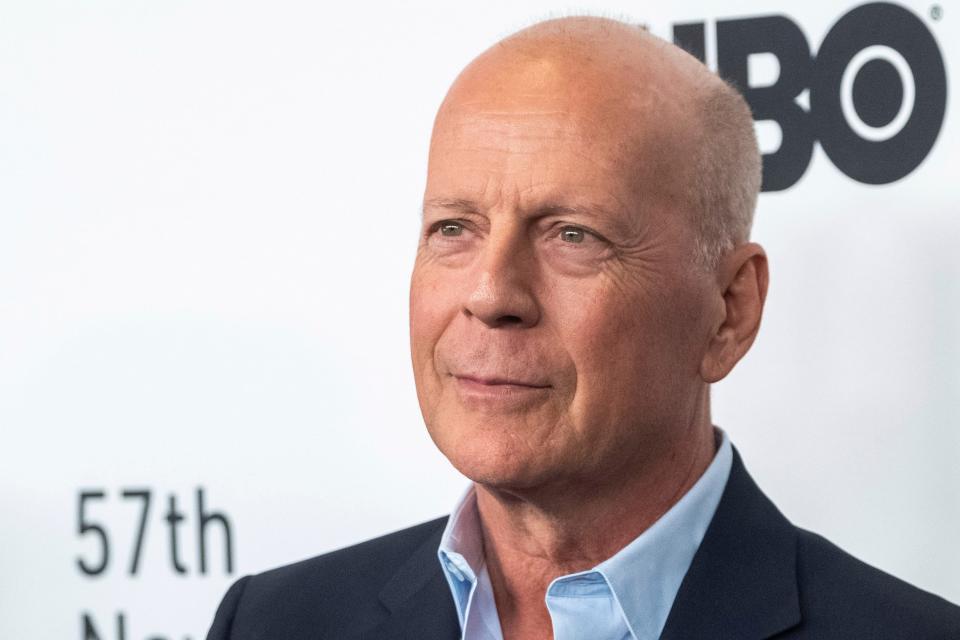

What is this dementia Bruce Willis has? How frontotemporal lobe is different from Alzheimer's

When Bruce Willis' family announced he had been diagnosed with frontotemporal lobe dementia last week, it came after his family had spent years seeking answers.

That's not uncommon, said Dr. Steven Steffensen, a neurologist at UT Health Austin's Comprehensive Memory Center at the Mulva Clinic for the Neurosciences. Not only does Steffensen diagnose and treat people with different kinds of dementia, including frontotemporal lobe, but his father also has this kind of dementia.

What is frontotemporal lobe dementia?

This kind of dementia involves a shrinking of the brain in the frontal lobe and/or the temporal lobe. Those are not the same areas where Alzheimer's is found; it is in the parietal lobe in the middle of the brain.

Frontotemporal lobe dementia has two primary types and other subtypes. The type a person has depends on which protein buildup is causing the dementia as well as where in the frontal or temporal lobe it is happening.

The two big types are behavioral and primary progressive aphasia (language).

People with the behavioral type often are angry or act out inappropriately. They are often misdiagnosed with a mental health disorder.

This type, Steffensen said, "is very hard on families and hard to find appropriate care."

Often, assisted living or memory care facilities are hesitant to take people with the behavioral kind because their symptoms are hard to manage and can affect people around them.

Primary progressive aphasia is the kind Willis has. Often it can be confused with just an aphasia, an inability to use language, or it can be confused with a stroke. Unlike with a stroke, though, the person is not slurring words.

Instead, the whole concept of language is reduced, especially in the subvariant that Willis has, called the semantic variant.

If people with this type of dementia are handed an apple, "they might recall having had it before but not know it's an apple. They lose the entire concept of the apple," Steffensen said.

It's not that they forget the word or can't say the word. They have no knowledge of the apple. It's as if they are seeing an apple for the first time, he said.

Often, the words they don't use every day go first, followed by common language. Steffenson likens it to landing in a foreign country and not speaking the language.

What is aphasia? Explaining the condition that's affecting Bruce Willis and millions of other Americans

When does frontotemporal lobe dementia happen?

It's one of the rarer forms of dementias. The behavior variant is hereditary, but the aphasia variant is not.

Both happen usually between ages 40 and 65. Many of the other dementias, including Alzheimer's, happen later in life.

People typically will have it for five to 15 years after diagnosis before death. Often they will die of something else before that.

Does this type of dementia affect memory?

Not primarily. All dementias in late stages tend to look the same, with effects on memory and the ability to walk, swallow and perform daily functions.

When it comes to testing for dementia, often a doctor will do a memory test to see if a patient can remember three words, or ask the person to draw a clock, or ask what day it is. People with frontotemporal lobe dementia might pass all of those tests.

Often they do not think anything is wrong with them. Members of their family will be the ones to sense that something is off either with language use or behavior.

"Most patients will say they don't have a problem," Steffensen said. "They lack any insight."

Often, they are able to live independently for a long time. Because it doesn't affect memory until in the late stages, people with this kind of dementia don't wander or forget to turn the stove off.

Steffensen's father was diagnosed in 2014 and is still living independently at age 72.

A valentine of gratitude: Love continues to grow after Alzheimer's diagnosis for Austin couple

How is it diagnosed?

Doctors look at symptoms such as a loss of language or behavioral changes. They rule out other potential causes for the symptoms. They also do an MRI to see if the brain is shrinking in these areas.

Even though doctors know an excess of certain proteins causes this, there is not a definitive way to diagnose it until an autopsy.

Finding help: 'Impacting someone's life': Amid challenges, Central Texas caregivers find the joy

Is there treatment for frontotemporal lobe dementia?

There isn't any medication specifically for this type of dementia, but one of the subvariants is thought to respond to some of the newer medications that slow Alzheimer's.

Steffensen focuses on symptom management. This includes medications to control behavior. For the aphasia type, speech therapy is helpful to prolong language use.

Steffensen also focuses on making sure that patients are as healthy as possible so they don't die of something else before this. He encourages people to work on other medical problems such as diabetes and heart disease, focusing on healthy eating, exercise, sleep and relaxation.

If doing all those things seems overwhelming, he suggests patients and their caregivers focus on doing two of them for a month and then build on those habits.

How to get help

Join a support group. There are groups for the caregiver and the person with dementia. AGE of Central Texas and the Alzheimer’s Association Capital of Texas Chapter host virtual and in-person groups.

Call the 24-7 help line, 800-272-3900. A licensed clinician is on the other end and can help you talk through issues and work out a care plan as well as connect you to resources.

Find respite groups. Churches often host them. You also can find them through AGE of Central Texas.

Find resources. Go to alz.org/help-support/caregiving and find resources by stages of the disease.

Attend a conference. Riverbend Church and AGE of Central Texas will host the GPS: Navigation for Caregivers Conference from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. Saturday. Riverbend Church is at 4214 N. Capital of Texas Highway. The conference is free, but attendees should register at http://www.TinyURL.com/GPSconference2023.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: How frontotemporal lobe dementia is different from Alzheimer's