Photos show how 700 of Titanic's 2,200 passengers survived thanks to rescue by the RMS Carpathia

The RMS Titanic sank on April 15, 1912 — almost 113 years ago — after it hit an iceberg.

The RMS Carpathia was over three hours away and came to rescue the stranded survivors.

Of the roughly 2,200 people aboard the Titanic, only about 700 people made it into lifeboats.

When the Titanic sank at approximately 2:20 a.m. on April 15, 1912, its survivors didn't know if, or when, rescue would come.

They sat, waiting, unknowing for an hour and a half in the dark, frigid Atlantic. Meanwhile, hundreds of frozen bodies floated nearby where the ship had slipped under the surface.

"'My God! My God!' were the heart-rending cries and shrieks of men, which floated to us over the surface of the dark waters continuously for the next hour, but as time went on, growing weaker and weaker until they died out entirely," survivor Archibald Gracie later wrote.

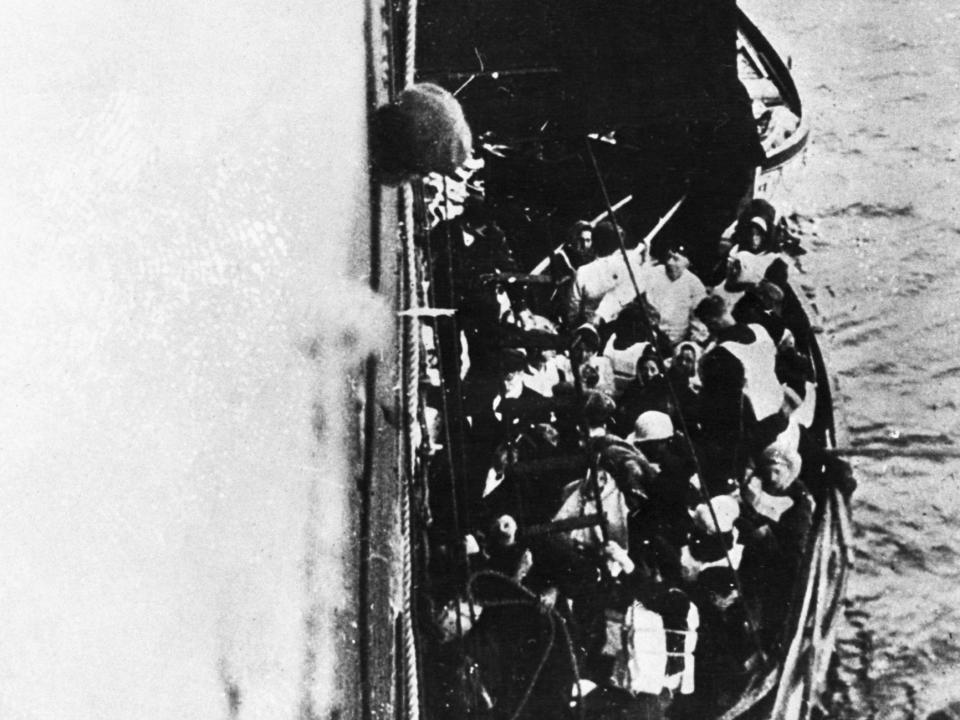

When the RMS Carpathia came to their rescue around 4:00 a.m., it took an additional 4.5 hours to move everyone from the lifeboats onto the ship.

These photos show how the Carpathia saved a fraction of the Titanic's passengers from the icy sea.

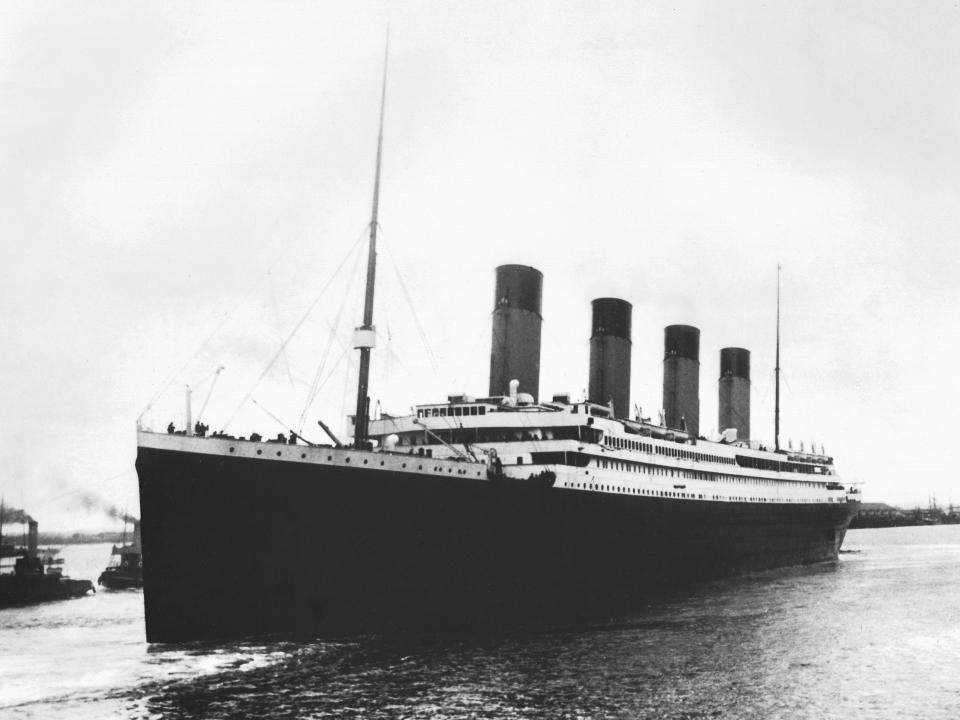

The Titanic set sail on its maiden voyage on April 10, 1912, with around 2,200 people aboard.

A British passenger liner, the Titanic was operated by White Star Line and was traveling from Southampton, England, to New York City.

Just before 11:40 p.m. on April 14, Titanic crewmembers spotted an iceberg, but it was too late for the ship to change course.

When the ship was about 400 miles southeast of Newfoundland, Canada, the two lookouts, Fredrick Fleet and Reginald Lee, spotted the berg.

Fleet and Lee were contending with an unusually calm ocean. With no waves breaking at its base, the iceberg was difficult to spot. Their binoculars were also locked in a cabinet, so they were using their naked eyes to scan the dark water on the moonless night.

While the night was clear, the lookouts later said the berg, between 50 and 100 feet tall, suddenly loomed out of the haze. One weather researcher has suggested a local phenomenon known as sea smoke, steam rising from the water, could have obscured the enormous frozen object.

First Officer William Murdoch ordered the ship's helmsmen to avoid the iceberg, but they couldn't turn in time. As the ship scraped the iceberg, it tore a hole in the side of the ship, rupturing at least five of the watertight compartments.

AD

By 2:20 a.m., the stern of the Titanic slipped below the water, and the surviving passengers never saw it again.

Thomas Andrews, the Titanic's designer, was on board and quickly realized the extent of the damage and alerted the captain.

Within an hour, Captain Edward Smith ordered the lifeboats lowered into the water, The BBC reported in 2012. As the ship's bow continued to sink, the stern rose into the sky.

Shortly after 2 a.m., the Titanic's lights went out. Soon after, the ship broke into two pieces, and the bow sank beneath the waves. Then the stern followed suit, sending hundreds of crewmembers and passengers into the sea.

Of the 2,200 or so people aboard the Titanic, only around 700 people made it into lifeboats.

There were 20 lifeboats aboard the Titanic, more than the 16 required for a ship that size. However, the boats only had capacity for about half of the passengers and crew, 1,178 people, Smithsonian Magazine reported in 2017.

Women and children were the first passengers to climb into the lifeboats. Many boats were launched below capacity, either because the crew were afraid they would collapse if fully loaded or because they didn't want to spend valuable time coaxing passengers onto the boats, according to "Titanic: A Night Remembered."

At first, passengers remained relatively calm as the Titanic sank, NPR reported in 2012. The mood changed as more people started arriving on the upper decks where the lifeboats were located, one survivor told The BBC in 1979.

Most of the lifeboats didn't return to rescue people who had plunged into the water.

As they rowed away, some lifeboat passengers feared the suction created by the sinking ship would drag them under. Others feared desperate swimmers would swamp the boats.

Emily Borie Ryerson's lifeboat returned to pick up survivors, mostly crewmembers, she testified during a senate inquiry into the event.

They "were so chilled and frozen already they could hardly move," she said. The water was 28 degrees Fahrenheit, according to "Titanic: 25 Years Later with James Cameron," a National Geographic special about the movie.

The SS Californian was near the Titanic when it sank, but its radio was shut off for the night.

When flares from the Titanic woke the captain, he assumed they were "company rockets," or signals passed between ships owned by the same company, not distress signals, the BBC reported.

Between 10 and 19 miles away, the Californian would have reached the Titanic much more quickly than the Carpathia, which was around 58 miles away.

The Californian had also messaged the Titanic earlier, warning of ice. The luxury liner's telegraph operator responded that he was busy, telling the Californian to stop sending messages.

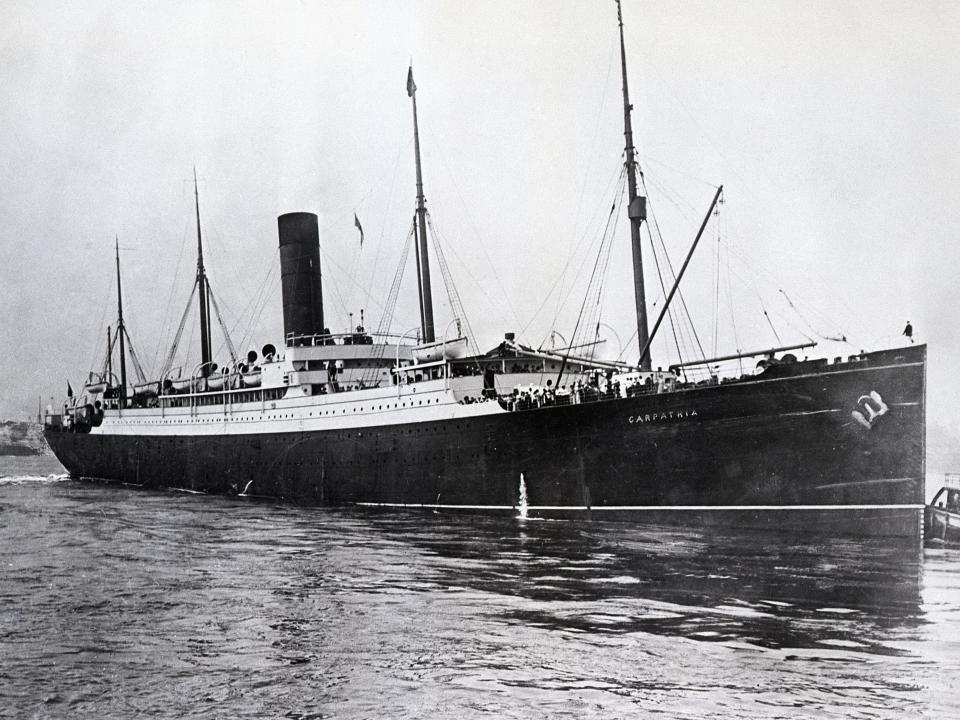

Instead, the RMS Carpathia responded to the Titanic's distress call and changed course to help.

Harold Cottam, the Carpathia's 21-year-old wireless operator, had planned to go to sleep for the night. First, though, he sent the Titanic a message to let them know he'd picked up transmissions meant for the luxury liner.

"Come at once. We have struck a berg," Jack Phillips, the Titanic's wireless operator, responded. At 12:35 a.m., Cottam alerted Arthur Rostron, the captain of the transatlantic passenger liner, who threw on a dressing gown and headed his vessel toward the sinking ship, BBC News reported in 2013.

"All this time, we were hearing the Titanic, sending her wireless out over the sea in a last call for help," Cottam told The New York Times in 1912.

Another ship, the Olympic, also heard the distress calls but was over 500 miles away, according to The Irish Independent.

Rostron ordered his crew to ready the Carpathia for survivors.

He stationed a doctor in each of the ship's three dining rooms, outfitting them with "restoratives and stimulants," per the US Senate's report on the disaster. The crew stocked the saloons with coffee, tea, soup, and blankets.

When the survivors came aboard, the chief steward and pursers would record their names so they could start sending them by telegraph.

Arriving around 4 a.m., the Carpathia came to the rescue of the survivors in the lifeboats.

The first lifeboat reached the Carpathia at 4:10 a.m. It took over four hours for the ship to pick up all of the survivors.

By 8:30 a.m., the final person from the Titanic's lifeboats had boarded the Carpathia.

The Carpathia discovered four bodies in the sea and lifeboats, which crew members buried at sea, according to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

Captain Rostron ordered the nearby Californian to search the area for any additional survivors.

Those aboard the Carpathia tried to accommodate the survivors, but the life-changing experience left many inconsolable.

"The people on the Carpathia received us with open arms and provided us with hot comforts, and acted as ministering angels," Titanic survivor Archibald Gracie later said. Many voluntarily gave up their beds to the rescued passengers, according to a 2017 article in "Voyage: Journal of the Titanic International Society 101."

While the doctors treated people for sprains and bruises, one saw women and children crying as the search for other passengers was called off.

Augusta Ogden offered coffee to two distraught women. "Go away," they said. "We have just seen our husbands drown."

Rather than continue along their original course, Carpathia's captain chose to return to New York City.

The closest port was Halifax, Nova Scotia, but getting there required traveling through more ice.

Rostron decided to return to New York, where the Titanic had been headed.

People flooded the White Star Line office in New York, wanting confirmation on the fate of the Titanic.

From the start, there were rumors that the company withheld information about the disaster, The Washington Post reported in 1912.

Philip Franklin, who was in charge of White Star Line at the time, denied knowing about the Titanic striking an iceberg shortly after it happened, Smithsonian Magazine reported in 2015.

Bad weather delayed the Carpathia's arrival in New York.

During the next few days aboard the Carpathia, survivors including Margaret Brown, who became known as the "Unsinkable Molly Brown" following the voyage, started a committee to help their fellow Titanic passengers.

The self-described survivors' committee raised thousands of dollars to thank the Carpathia's crew. Brown, Emma Bucknell, and Martha Stone created lists of basic necessities for the other survivors.

They camped in a dining room for hours, listening to other passengers as they "poured out their grief and story of distress," Brown later wrote.

As the Carpathia approached New York, reporters hired tugboats to sail alongside the ship to talk to survivors.

Carlos Hurd, a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was aboard the Carpathia when it raced to help the Titanic. He and his wife, Katherine, interviewed survivors and wrote down their stories.

Rostron wouldn't allow him to use the telegraph during the trip back to New York, so he tossed his notes to his colleague aboard one of the boats, The Missoulian reported in 2012.

Other journalists shouted at passengers through megaphones, offering $50 or $100 for interviews, WNYC reported in 2012.

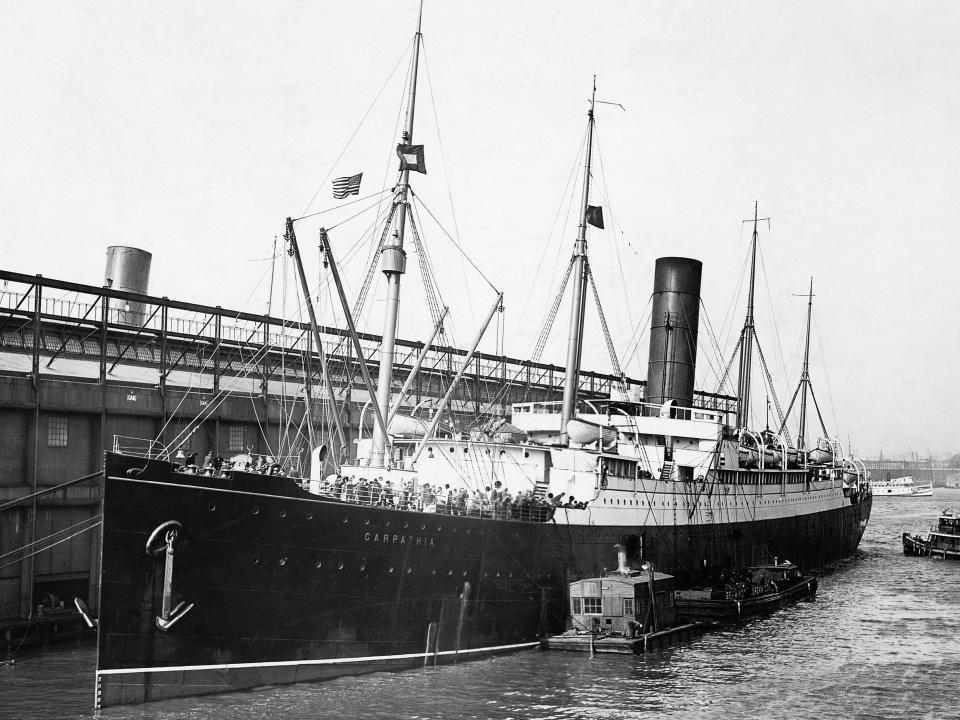

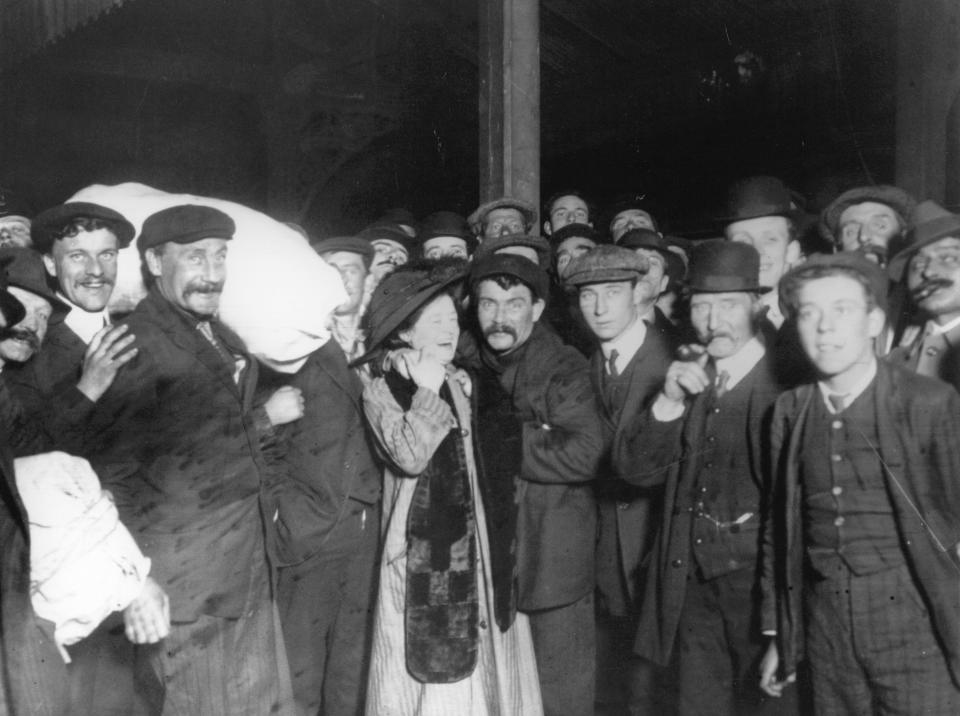

The Carpathia eventually docked at Pier 54 on April 18 at around 9:15 a.m.

The ship had left from the same dock only seven days earlier, The New York Times reported in 2012.

Thousands of people were waiting to welcome the survivors.

Families of passengers arrived hoping to be reunited with loved ones. Ambulances lined the streets waiting to tend to the survivors, The New York Times reported in 2010.

The Carpathia had rescued over 700 people from the freezing Atlantic.

Of the roughly 1,500 people who died aboard the Titanic, nearly 1,200 were crewmembers or third-class passengers.

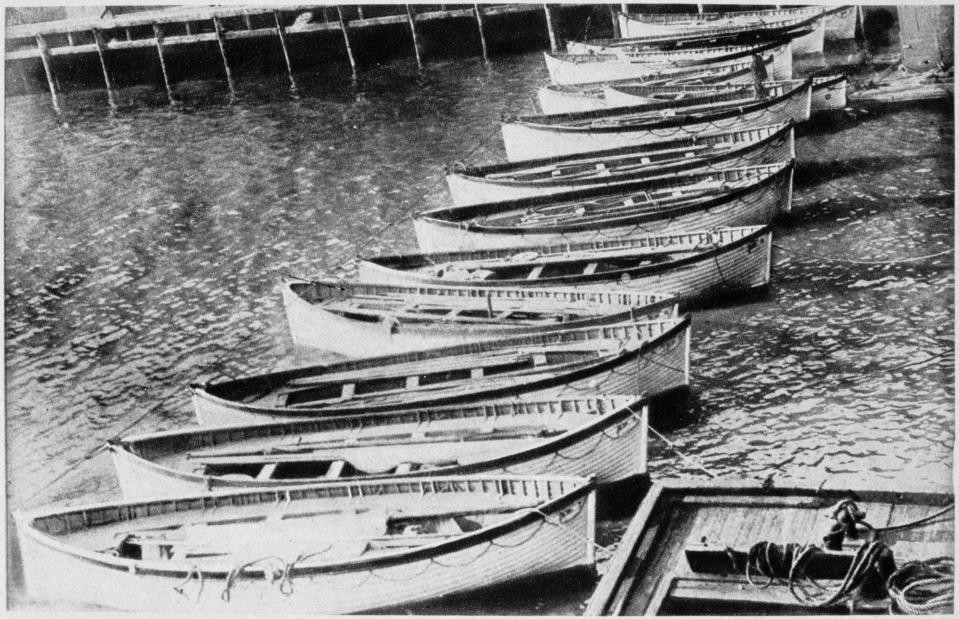

The Carpathia's crew returned 13 of Titanic's lifeboats to the White Star Line.

Before docking to let the passengers off, the ship stopped to drop off the lifeboats at the White Star Line's Pier 59, according to the Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Practically overnight, passenger liners needed to have enough lifeboats for everyone on board, The New York Times reported in 2012.

Halifax later became the main port for ships retrieving bodies from the wreckage.

Three ships dispatched from Halifax were able to retrieve over 300 bodies from the wreckage, or one in five victims, according to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

The first vessel sent to retrieve bodies, the Mackay-Bennett, ran out of embalming supplies — the ship didn't expect to find so many bodies in the water — forcing crew members to bury more people at sea than intended.

About half of the recovered bodies are buried in Halifax. Relatives claimed 59 bodies and returned them home. Most of the dead were crew members and third-class passengers who were trapped on lower decks, ABC News reported in 2020.

For his rescue efforts, Rostron received a Congressional Gold Medal.

Rostron was reluctant to speak publicly about his role in the Titanic rescue, though he did write an autobiography, "Home from the Sea," detailing his account of that fateful night.

This article was originally published in April 2020 and updated on January 13, 2025.

Read the original article on Business Insider