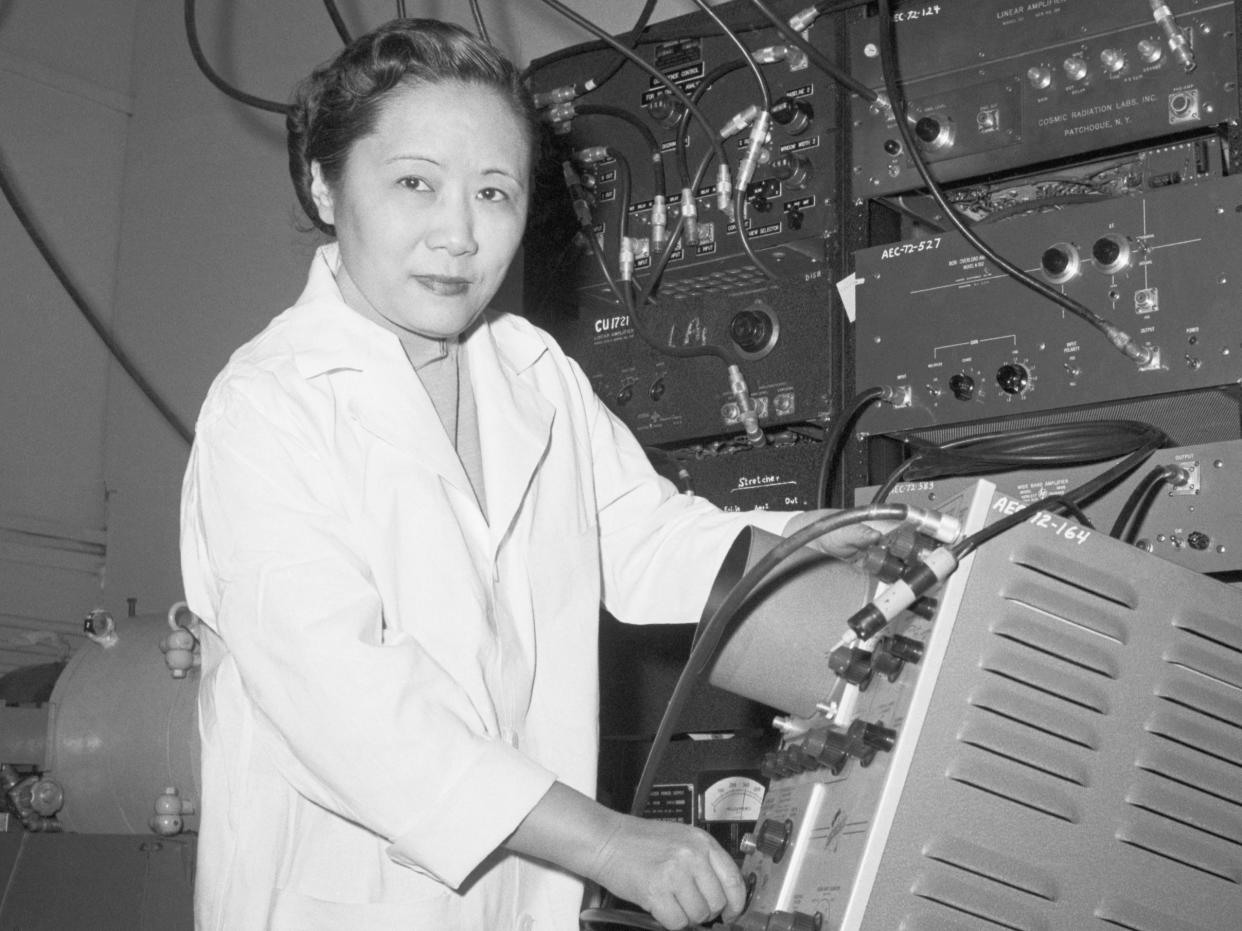

Chien-Shiung Wu, a nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, spent her career fighting for gender equality in science

Chien-Shiung Wu was a Chinese physicist who was instrumental to the Manhattan Project.

Wu was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize for Physics after being denied a Nobel Prize that her male colleagues received.

Wu also advocated for gender equality, refusing to adopt her husband's last name and demanding equal pay.

Christopher Nolan's blockbuster film "Oppenheimer" largely omits the women and the people of color who worked on the real-life Manhattan Project, instead zeroing in on the white men involved in the US government's atomic bomb initiative.

Chien-Shiung Wu is a physicist who broke through both gender and racial barriers in 1940s America, wowing the science community with her significant contributions to the Manhattan Project.

Wu was born in Jiangsu province, China, on May 31, 1912, to a family of intellectual revolutionaries. Wu's mother was a teacher who valued education for both genders, while her father was an engineer who also advocated for women's equality. He became an activist during the 1911 Revolution, which ended imperial rule and established the more modernized Republic of China.

Wu was especially close with her father, who encouraged her interests and surrounded her with books, magazines, and newspapers. Instead of children's stories, Wu would listen to her father read from scientific journals, according to her biography. She attended an elementary school for girls her father founded.

A gifted student, Wu went on to study physics at prominent institutions in China. A female professor encouraged her to earn her Ph. D. abroad at the University of Michigan. When she was 24 years old, Wu set sail for the United States in August 1936. It would be the last time she saw her parents alive: Although her family survived the impending world war, the establishment of Communist rule in 1949 made it impossible for Wu to travel home for many years.

The 'Chinese Madame Curie'

Her plans to study in Michigan quickly changed after she visited the University of California, Berkeley. There, she met the Nobel Prize-winning nuclear physicist Ernest Lawrence, who, along with other pioneering researchers like J. Robert Oppenheimer, were turning the campus into the epicenter of the Manhattan Project. (It may have bolstered her decision to have discovered that at the relatively conservative Michigan, women weren't allowed to use the front entrance, per Wu's biography.)

Wu quickly impressed her colleagues with her work on nuclear physics. Lawrence described Wu as "the most talented experimental physicist he had ever known, and that she would make any laboratory shine."

Oppenheimer himself reportedly said, "Go invite Ms. Wu — she knows everything about the absorption cross section of neutrons." (According to her granddaughter, Wu called him "Oppie," while Oppenheimer called her "Jiejie," a term of endearment meaning "elder sister" in Chinese.)

In his autobiography, prominent Italian physicist Emilio Segrè compared Wu to her heroine Marie Curie, but said Wu was more "worldly, elegant, and witty."

But sexism and anti-Asian racism that only intensified after the Pearl Harbor attack prevented Wu from securing a good academic job. She married her colleague Luke Yuan and moved to the East Coast. Wu eventually accepted a job at Princeton University, becoming the first female faculty member in the history of its physics department.

The Manhattan Project

In March 1944, Wu was recruited to the Manhattan Project at Columbia University, where she helped develop the process for separating uranium — crucial to producing enriched uranium to fuel the atomic bombs at the Oak Ridge facility.

Wu also helped solve a problem involving an isotope's chain reaction that stumped the other scientists. Enrico Fermi, who became the associate director of the laboratory at Los Alamos in 1944, was reportedly told to "ask Ms. Wu."

It turned out that Wu's graduate school thesis had been on the isotopes in question, which were instrumental in solving the issue.

Like many other scientists involved in the project, Wu later distanced herself from the Manhattan Project due to its destructive outcome.

"I have confidence in humankind," Wu said, years later. "I believe we will one day live together peacefully."

Wu's legacy

After the Manhattan Project, Wu continued to advance the science community's understanding of nuclear physics.

In the late 1950s, Wu devised a series of experiments — dubbed the "Wu experiment" — that disproved the "law of conservation of parity," which posits there is a fundamental symmetry in the behavior of things. The findings were groundbreaking, and Wu's male colleagues who had originally come up with the theory won the Nobel Prize in 1957. Wu, however, did not.

"Although I did not do research just for the prize, it still hurts me a lot that my work was overlooked for certain reasons," she later wrote to her friend.

Wu was later awarded the first Wolf Prize, considered the second most prestigious award after the Nobel Prize, in 1978.

Out of the lab, Wu continued campaigning for gender equality in her profession, correcting anyone who called her by her husband's last name and insisting on being paid the same as her male colleagues at Columbia.

"I wonder," she once asked at a symposium of women, "whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment."

Wu also advocated for human rights issues, protesting the crackdown in China in the wake of the grisly Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

After Wu retired in 1981, Columbia University hosted a celebration "to honor the First Lady of Physics." Wu died in 1997, and her ashes were buried in the courtyard of the school her father had founded.

Read the original article on Business Insider