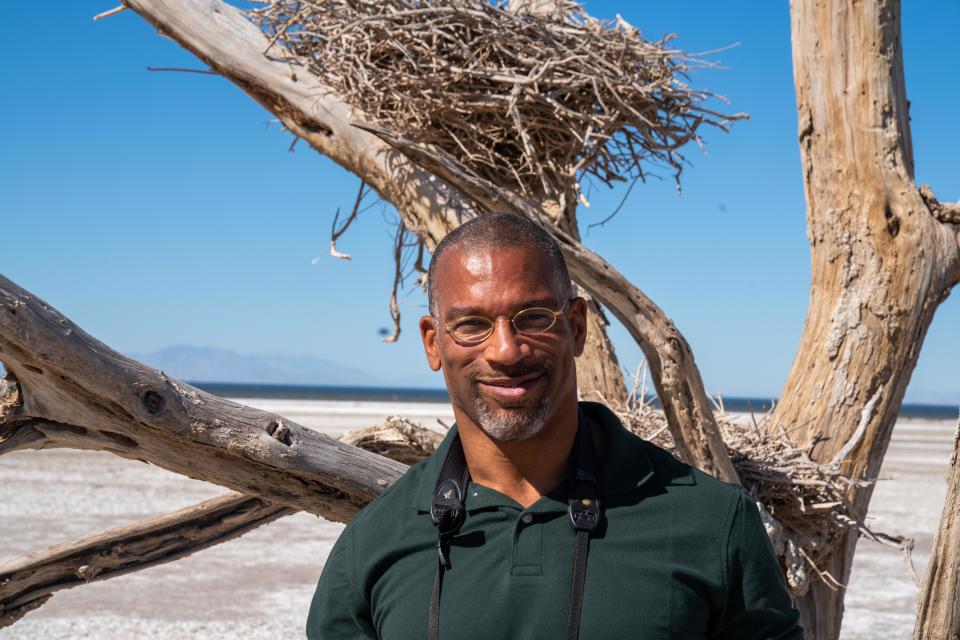

The Central Park Birder, Christian Cooper, Hosts New National Geographic Wildlife Show

“Through a strange twist of fate, I had become the most famous birder in America, which is not hard because who the hell knows who birders are in the first place,” says Christian Cooper, of gaining national attention in 2020 when a white woman in Central Park called the cops on him after he asked her to leash her dog in a protected wildlife area. It’s an incident “I psychologically moved on [from] three minutes later,” he says. “Maybe it’s just being Black in America, but you develop a fairly thick skin.” (The incident inspired the founding of Black Birders Week, now in its fourth year.)

Cooper was in Central Park that day to go birding. It’s a lifelong passion that the NYC Audubon board member will soon share widely with the world as the host of his own National Geographic series, Extraordinary Birder With Christian Cooper, out June 17 on National Geographic Wild and hitting Disney+ on June 21.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

The gig came about after he was approached by Nat Geo senior vp development and production Janet Han Vissering. “She called and said, ‘I want to do a birding show and I want you to do it,’ ” says Cooper, who in the ’90s worked as a writer on Marvel and Star Trek comic books, where he introduced pioneering LGBTQ characters such as Victoria Montesi (Marvel’s The Darkhold No. 1) and Yoshi Mishima (Starfleet Academy).

The six-episode Nat Geo series follows Cooper to six areas of the U.S., including Puerto Rico, Hawaii and Palm Springs. In the latter, he encounters ravens, burrowing owls and the Costa’s hummingbird, the second-smallest hummingbird in North America. He hopes the show helps inspire people to come together to preserve habitat on this planet for birds. “We have a crucial role,” he says. “As individuals, we can have an impact on this.”

Cooper — also the author of a new memoir, Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World — spoke further with THR about his love of birding; why bird watching is not an inclusive term for the activity; traveling to Ecuador to see one of his grail birds; and how Central Park for him remains a place of beauty.

A lot of people may think there aren’t a lot of birds in Palm Springs because it’s a desert. What is it like to go birding out there?

The desert has its whole range of species. I basically had a big hand in picking the locations and one of the reasons why I picked Palm Springs is because I spend my winters out there. So it’s an area I know fairly well and have an interest in. The main bird we focus on is the raven, because ravens are big and incredibly smart. They’re probably the smartest birds there are. And that’s pretty darn smart, actually. At least dog intelligence and maybe even approaching chimpanzees. The whole crow family is a very smart group of birds. And so you’ve got this super-smart bird that is being super successful in Palm Springs. We actually went to one place outside of Palm Springs which is basically Raven City. They all kind of gather there by the thousands in one giant roost. And this is behavior that was new to me. Because in my experience, ravens are generally seen in groups of two to three. In Palm Springs, it’s like something out of The Birds. So it was pretty awe-inspiring to see that. But one of the problems is that that causes some ecological imbalances because there are so many ravens. They’ve learned to thrive on our trash. They learn how to maximize what humans make available to them as resources. And that means there’s so many ravens that it can cause problems out in the desert. So we talk about that, and we explore some of the nonlethal solutions to helping to control the raven population.

Where are good places to go birding out near Palm Springs?

There’s any number of places you can go. You can go to something called the Prescott Preserve, which is a brand-new preserve right in the middle of Palm Springs. It used to be a golf course and now it’s a preserve that has bobcats and coyotes and, of course, birds. Right in the middle of Palm Springs, you’ve got this amazing bit of nature. You can also go out to the Salton Sea, while there still is a Salton Sea. That’s one of the things we did on the show. It’s a crucial stopover point for migration on the Pacific Flyway. For birds traveling along the West Coast, they need a place to stop and rest and refuel and the Salton Sea is one of those crucial places, and it’s in dire ecological shape. And if you are hiking a canyon like Tahquitz Canyon, you can be birding and see great things like rock wrens and canyon wrens and Western bluebirds, which are just gorgeous. When they are in their breeding plumage, they’re just electric blue.

Do you have a grail bird that you’ve gotten to see?

In the middle of COVID, I got this email from one of my fellow New York City Audubon board members and he has been to Ecuador a number of times. A guy down there had told him that he had found an active harpy eagle’s nest. Now, the Harpy eagle is the biggest eagle in the world. It’s enormous. And I’ve never seen one. If you know where there’s an active, accessible nest, you’re pretty much guaranteed to see the bird. But it’s the middle of COVID. I’m like, “Forget it. He’s already arranged the whole trip.” So I got on a plane down to Ecuador in the middle of COVID and ruined a pair of hiking boots walking through this strange surface that’s not quite ground, not quite swamp so that when you step on it, you kind of sink ankle-deep. And then this enormous harpy eagle with this crest of feathers on her head was guarding her nest. And at one point you just see this enormous wing stretch out. Whoa. It was just an awesome experience. So it was a thousand percent worth heading down to Ecuador for. Plus, there’s a TV movie, I think it was called Harpy, from the ’70s, where this guy has a trained harpy eagle that I think he trains to attack and kill his wife so he can get rid of her. And I saw this as a kid. So blame that TV movie for planting the harpy eagle in my consciousness.

Can you talk more about the incident in Central Park and how you look back on it now?

It’s always very interesting to me that people say, “Oh, we’re so sorry for your trauma.” And I’m like, “What trauma?” That situation didn’t have that kind of power over my existence. Maybe I’d have a different opinion if I’d been thrown to the ground by the cops and handcuffed. But none of that happened. So, you know, you move on. There’s so much more to the park and to what I’ve experienced in the park. In that very spot where that happened, I have memories of mourning warblers coming out onto the woodchip path. I have memories of hooded warblers and Lincoln’s sparrows and Blackburnian warblers, which have this DayGlo, fiery orange throat. It’s like — what happened in the park can’t compare to that. It just can’t. It’s beautiful.

What is one of your earliest bird memories?

The bird that got me started birding was the red-winged blackbird, growing up in the suburbs of New York on Long Island. I kept wondering, “What are these crows with red on their wings? Did I discover a new species of crow as a kid?” And it turns out they were red-winged blackbirds. That’s what birders call your spark bird. And in fact, there’s a little red-winged blackbird on the cover of my memoir.

Have you ever gone birding in and around L.A.?

The thing that really got me to the outskirts of L.A. was a snowy owl. You may have read about that in the press. A snowy owl showed up out of the blue, way too far south, on the top of a roof in some suburb in Orange County where it absolutely did not belong. And a bunch of us from Palm Springs just hopped in a car and drove out and we were like, “We gotta see this.” And sure enough, there was this big old snowy owl sitting on top of a rooftop. They like vast tracts of open fields or dunes that they can hunt in. They’re used to hunting in arctic tundra. They’re looking for something that looks like that. Not for tract housing in the suburbs. And yet here he was.

Any advice for people who want to get into birding?

The secret is: Get out there and look and listen. It helps if you have a pair of binoculars. That is for many people a barrier to entry because they can be a pricey bit of equipment. But beg, borrow, steal, get somebody’s hand-me-downs from a birder who is upgrading and replacing their old pair. If you don’t have binoculars, just use your eyes and your ears and go out there and drink in what is freely available to all of us. And I don’t care whether you’re rich or poor, whether you’re Black, white, green, purple, whether you’re gay, straight, bi, trans, you know, whether you are abled or differently abled. I don’t care if you’re blind. I met a blind birder when we did the shoot in Puerto Rico who used his ears. He could sort the sounds he heard. And that’s one reason why we now say birder instead of bird watcher. Because you don’t have to be watching, you can be listening. And eventually, you’ll find ways to get more and more pulled in.

A version of this story first appeared in the May 31 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter