Austin heart transplant recipient taps mental strength during long hospital stay, recovery

Matt Hudson, 53, isn't the kind of guy to just sit around. He got back into mountain biking in his 40s and also loved to go running on his family's San Angelo ranch.

"I try to be outside 24/7," he said.

Yet for 111 days in the summer of 2020, Hudson was confined to a hospital room at Seton Medical Center in Austin — too sick to leave — while waiting for a heart transplant.

"I went nuts, totally," he said.

His doctors had to find a way to keep Hudson both physically and mentally well while waiting for a heart, and Hudson had to figure out how to keep pushing himself to make it until the transplant and then recover from it.

A spirit of gratitude: Austin mom shares journey from childbirth to heart transplant

During his time in the hospital, heart transplant recipient Kristen Patton came to his bedside and told him about the Transplant Games, an Olympics-style event for people who have had an organ transplant.

"This is it. This is my goal," he said.

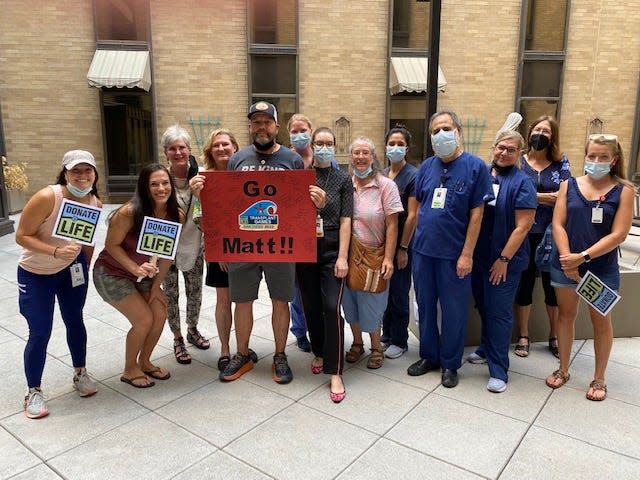

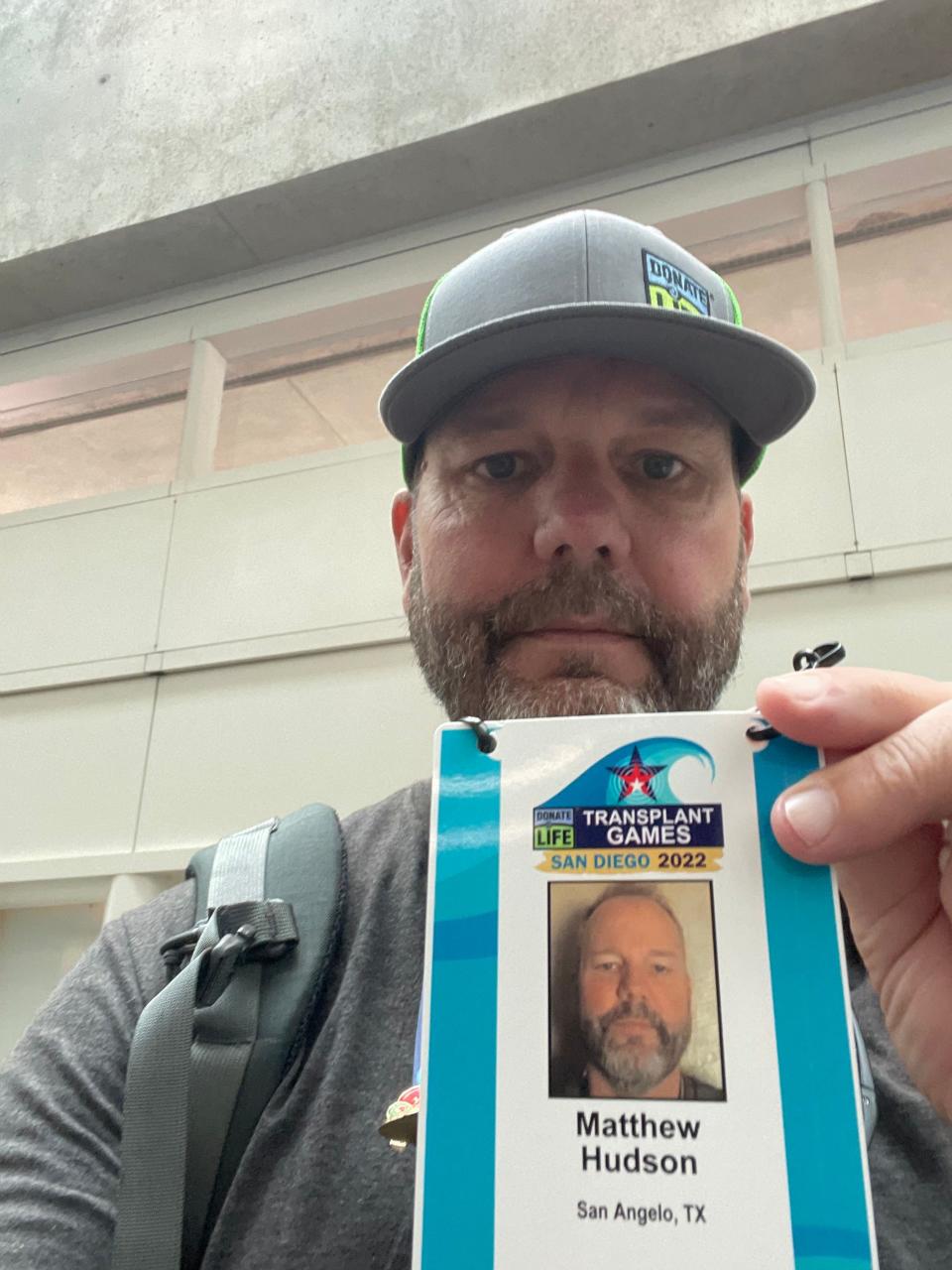

Last summer, two years after being listed for a heart transplant, Hudson competed in the cycling event in the 2022 Donate Life Transplant Games in San Diego. He finished fourth.

"I thought I was going to be in better shape than everyone else," Hudson said. But now he has something more to work toward: next year's transplant games in Sydney and the chance to medal.

"I'm looking forward to it," he said.

More transplant stories:For Austin man, second heart transplant doesn't end connection to first donor's family

Something is wrong

Hudson's heart failure started in 2015. He had been running and mountain biking "and just killing it," he said.

Then one day, "I just wasn't me. I couldn't put my thumb on it."

He stopped exercising, but then he checked his heart rate, and it was 43 beats per minute. The next day he was dropping off paperwork at his doctor's office for an upcoming physical and asked the nurse to check his heart rate. It was exactly the same, 43. Anything below 60 is considered low.

His primary care doctor sent him to a cardiologist, who later put in a pacemaker.

"I never got back to where I was," he said. But he kept pushing through.

In 2019, his heart struggles "hit again and hit with a vengeance," Hudson said.

He was on the San Angelo ranch and having a hard time breathing. When he took off his snake boots, his legs had swollen to 18 inches around the calves. "We had a problem," he said.

Yet he stayed on the ranch through the weekend. That Monday, he called his cardiologist at the time and was told to get to the emergency room. He was fitted with a larger pacemaker with a defibrillator.

"After a month, it wasn't getting any better," Hudson said. "I was gasping for air. It was hard for me to carry groceries. This is not good."

That cardiologist told him he needed a heart failure specialist. They sent him to Dr. Raymond Bietry at Ascension Seton Medical Center in Austin.

Hudson actually had sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that often is in the lungs, lymph nodes and skin. Hudson's had progressed to his heart, which was affecting his heart's ability to coordinate his heartbeat.

'Impacting someone's life': Amid challenges, Central Texas caregivers find the joy

"He probably had sarcoids in his heart for a number of years," Bietry said.

It can be treated with anti-inflammatory medications and steroids, but "after evaluating his heart, it was too far along," Bietry said. It was already failing and in the end stages.

"He had me diagnosed in a day," Hudson said. "My option was a transplant. That was it. I definitely didn't take it well."

Bietry adjusted Hudson's medications to help him feel better and started the process of getting him on the transplant list.

Hudson did feel better at first, but it was gradually getting worse.

"I was OK during the day, but when I was trying to rest at night, I was gasping for air," Hudson said.

It finally got to the point where Hudson had been up 36 hours without sleep. He was hospitalized at Seton to get stabilized and sent home with a medication pump.

It worked for two weeks. Then on June 30, 2020, Hudson checked into Seton Medical Center to await his transplant.

Wanting to give up

About three weeks into his stay, he told his doctors, "if I'm just going to sit here and wait, I can do this at home ... I want out. There is no way I can do this."

Bietry assured him, "You can do this; you have to do this."

Bietry explained that because Hudson's disease had progressed, he needed to be in the hospital to be monitored and be given intravenous medications. His hospitalized status also moved him up on the transplant waiting list. "You've got to push forward. You've got to find things to do," Bietry told him.

Hudson got a guitar and tried to learn how to play. He watched inspirational videos and read the Bible. He made a deal with the cardiac rehabilitation team to take him outside at least five days a week. And they put a stationary bicycle in his room that he could ride if he would take it easy.

Because his hospitalization was during COVID-19 visitation restrictions, Hudson was alone there. For his birthday, his medical team surprised him by bringing him outside for cardiac rehab. That day, his whole family came to see him at the front of the hospital.

"It was so awesome," he said.

People in heart failure lose weight, muscle mass and endurance. That was happening to Hudson, but he didn't want to eat the hospital food. The hospital brought the chef to his room to prepare the menu he wanted. That meant a heaping pile of spaghetti, garlic bread and salad with French dressing.

"I was spoiled rotten, you could say," Hudson said.

The wait is over

He also made a deal with the staff. Every Sunday morning he was going to attend church virtually, and he was not to be disturbed from 8:30 to 9:30 a.m.

They broke that deal on Sept. 27, 2020. "That door opened, and it wasn't anyone I recognized. I went on to say something like, 'This is my time.❜ ❞

He remembers these words: "We have a heart." Hudson still gets emotional and choked up just thinking about it.

"It was pretty chaotic after that," he said.

But he couldn't notify his family yet — not until they were absolutely sure this heart was coming to Hudson. On two other occasions the staff had thought a heart was going to be matched to him, but both times it fell through.

"You're at the top of your game, but it just slams you down," he said of those experiences.

Sure enough, he was told to pack up his stuff, which after more than three months in the hospital had become substantial. He would be going into surgery to get his new heart the next day.

He doesn't recall much after that, but he remembers telling his doctors that he had some goals.

"I want to walk the day after, and I want to be out of here within a week," he said.

"That didn't happen," Hudson said, but he was determined to get back to his old self as soon as possible.

Developing a transplant program: EXCLUSIVE: First heart transplant at Dell Children’s gives life to new program and a boy

No quick recovery

When Hudson woke up after surgery, he was on a ventilator. His kidneys were struggling, and he was on dialysis. He later had pneumonia. And his brain wasn't working quite right. He could understand everything people were saying, but he couldn't communicate. He also had delirium.

"Once I made it through all of that, it was almost like a dream," he said. "I didn't believe it."

He pulled his shirt up and saw his scar.

"It was a complete shock. How are you even alive?" he said.

He went from barely being able to walk to being able to leave the hospital Oct. 22, three weeks after his transplant.

"There are baby steps," Bietry said about transplant recovery. "You can't just get a new heart and snap your fingers. It can take time for things."

Working his way back to the bike

Hudson was having trouble finding a cardiac rehab facility close to Fredericksburg, where he has a house. But his doctors knew it was equipped with a full gym, so they allowed him to stay at home and do his own rehab.

He set a goal of being back on a bicycle by Christmas.

Those first few days, his sister had to help him get into the gym. "I had to have some help. I was pretty weak," he said.

First he worked on sitting and standing. Then he moved to the stationary bike.

"The first day, I did 2 miles. I was so impressed with myself. This is incredible, and it felt good, but I was completely exhausted," he said.

"Every day I set goals. I pushed too hard; I know I did."

And then it was time. He went outside and got back on his mountain bicycle.

"I was a little wobbly," he said. "But it was a sense of freedom. I was like, 'Let's go!' I didn't last very long," he said.

Sometimes Hudson's drive scares Bietry.

"He's a patient who constantly challenges my comfort level," Bietry said. "He's pushing the limits of what his body is doing, but we don't go through this whole process for people to reside at home and live in a chair."

Sometimes Bietry has to remind him: "You're not normal. You've had a heart transplant, but you're able to do amazing things."

Bietry will continue to monitor Hudson for infections, coronary blockages and even cancer, all of which carry an increased risk for heart transplant patients.

"Transplant is not a permanent solution," Bietry said. Sometimes a heart can last multiple decades, but the average is about 12 years, he said.

The greatest gift

Just before Thanksgiving 2021, a full year after his transplant, Hudson received a card from his donor's mother. Inside were her son's dog tags. He had been in the military.

"It was very emotional," Hudson said. He wasn't quite ready.

"It took me probably five or six months to respond. It was probably the hardest thing I've ever had to write," he said.

He wrote her an email. Then they started texting back and forth.

"There were days where I was ready to meet her," he said. "And then there were days where, 'no way; I can't do this.❜ ❞

And then they decided she would come out to meet him on the ranch in San Angelo. They spent the weekend together, with Hudson telling her about his life and her telling him about her son.

"He and I have a lot in common. It's almost bizarre," he said.

When she left that Sunday, it was very emotional. She returned the next day, and they spent a few more days sharing stories.

"She's part of this family," he said. "What a fabulous lady. Her son was incredible."

Keep pushing

This experience has been humbling to Hudson, but he keeps pushing himself.

Every day, he wakes up around 5:30 a.m. He checks his vitals to make sure everything is working well. He heads to his gym and puts in an hour to an hour and a half. Then he hits the bike and rides 10 miles, sometimes twice that.

He's gotten used to the road bike he competes with in the Transplant Games, but he still misses his mountain bike. The road bike "is not my favorite thing. I do love the dirt," he said.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: From heart transplant to competitive cycling: Meet Matt Hudson