American history resides in Hamilton: Capt. John Cleves Symmes and his 'Hollow Earth' theory

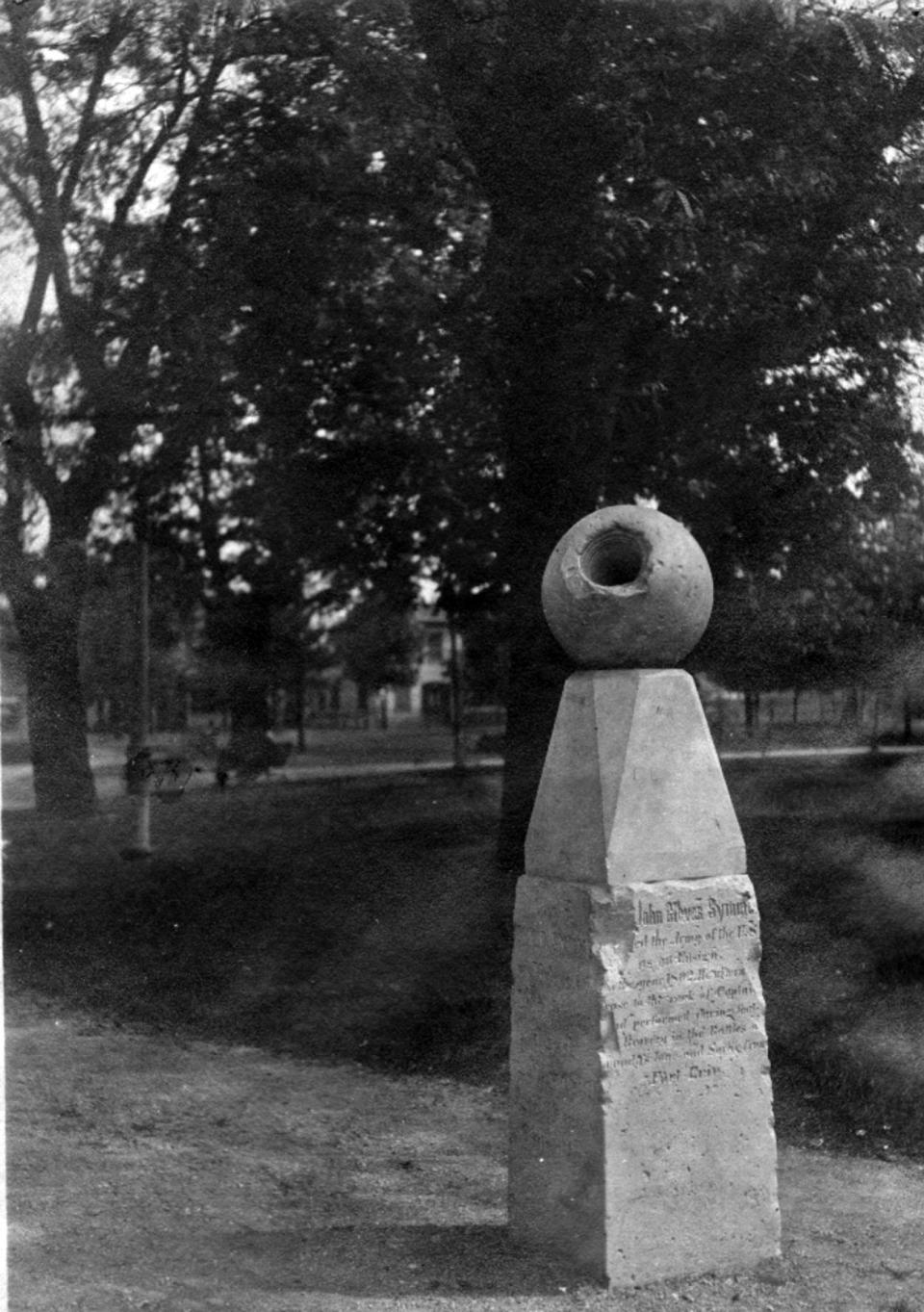

In the middle of a city park in Hamilton, Ohio, you can find a peculiar monument to Capt. John Cleves Symmes and his Hollow Earth theory.

The time-and-weather-worn stone obelisk, topped by a metal orb with a hole through it, is enclosed by an iron fence in Symmes Park.

The original monument (minus the concrete base added in a 1991 renovation) was placed as a grave site memorial by Symmes’ son, Americus Symmes, in 1873, according to a plaque at the site. The orb on top is a replica of a model that Symmes used in his lectures to demonstrate his belief that the Earth was hollow.

Not the same John Cleves Symmes many are familiar with

If the name is familiar, that’s because Symmes shared it with his uncle, also John Cleves Symmes, the Revolutionary War patriot who in 1788 bought more than 300,000 acres known as the Symmes Purchase that would make up most of what is now Hamilton, Butler and Warren counties. To avoid confusion, the nephew was referred to by his rank or as John Cleves Symmes Jr.

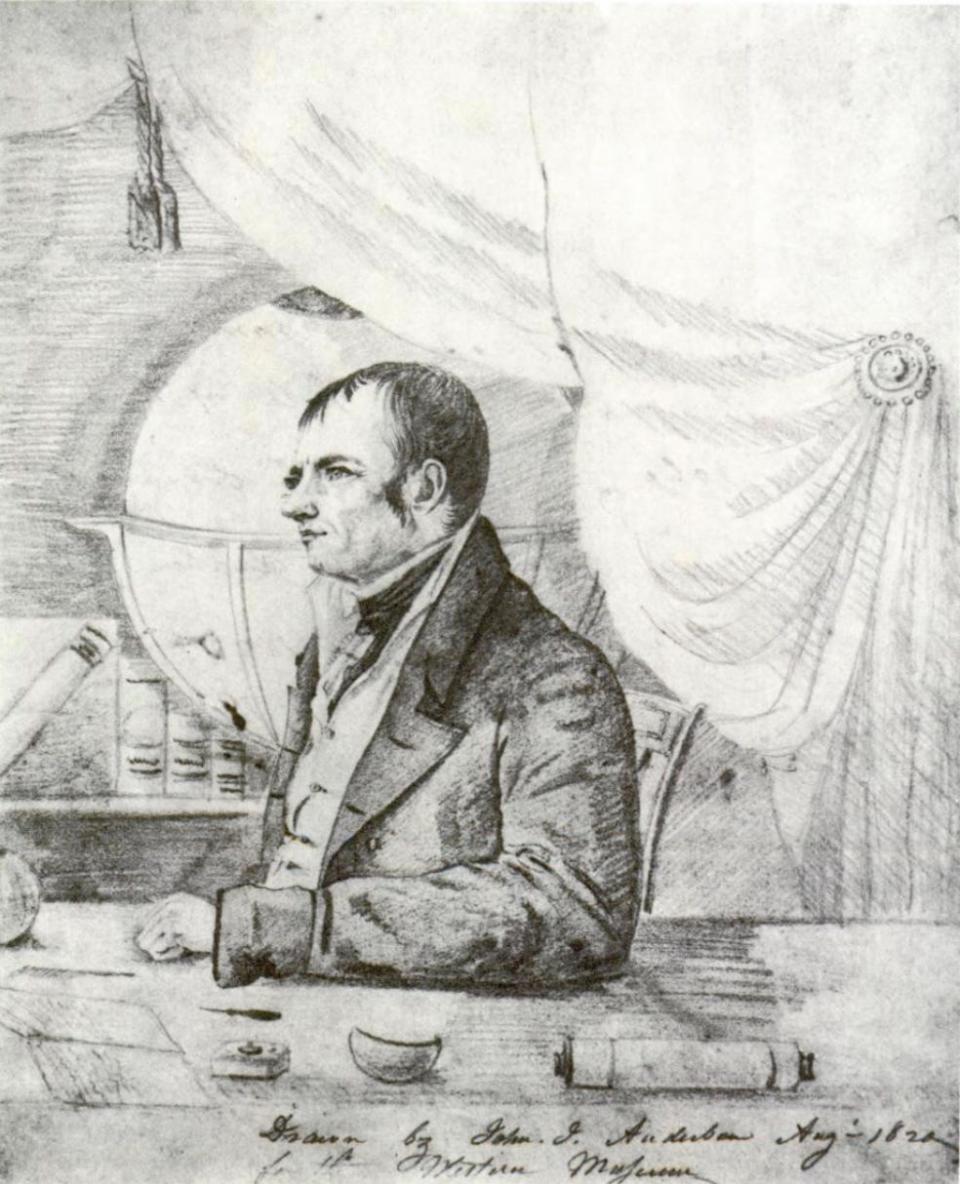

The younger Symmes is best remembered for promoting his theory that the Earth was made up of hollow concentric spheres and was habitable inside, an idea that was largely ridiculed 200 years ago but did have some believers who called Symmes the “Newton of the West.”

Like his uncle, Symmes was from Sussex County, New Jersey, born about 1780. In 1802, he received a commission as an ensign in the U.S. Army and rose to the rank of captain while serving in the War of 1812.

After he left the Army in 1815, he settled in the frontier town of St. Louis and worked as a trader, a profession at which he was not very apt. During this time, he began dreaming up his theory that the Earth was hollow based on his observations of nature and the planets.

‘I declare the earth is hollow’

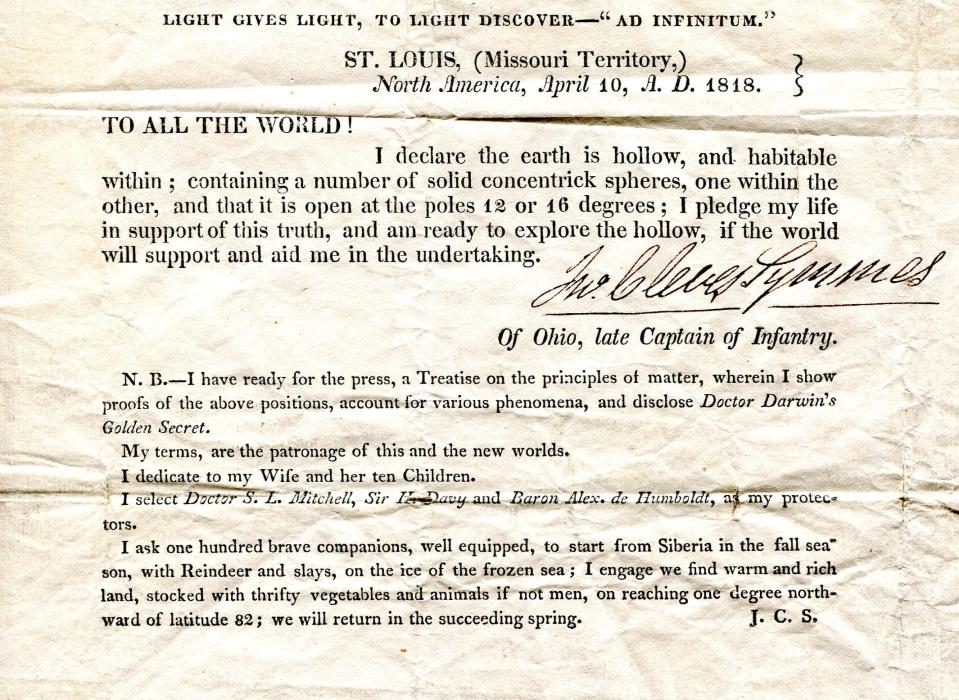

On April 10, 1818, Symmes published his Circular No. 1, addressed “To All the World!” and sent to newspapers, politicians, universities and philosophical societies throughout America and Europe.

He wrote: “I declare the earth is hollow, and habitable within; and that it is open at the poles 12 and 16 degrees; I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.”

Symmes theorized that the Earth was comprised of five concentric spheres, with the 1,000-mile-thick crust being the outermost sphere, and that it was open at the poles. The Arctic (North Pole) opening was estimated to be 4,000 miles across and the Antarctic (South Pole) opening 6,000 miles wide.

Symmes seemed to eschew Newton’s laws of gravity for his own creative notion, that the universe was made of aether, which held the planets in place, and that matter rotating in the aether formed hollow concentric spheres due to centrifugal force pushing the matter away from the axis.

Furthermore, he reasoned that the interior of the planet was habitable with animal and vegetable life. He noted that some Arctic animals migrated north and must find something to eat up there – so they must use the north opening to enter the warm, interior world.

In his declaration, Symmes also proposed to gather 100 “brave companions” to accompany him to Siberia and a voyage to the north opening where “I engage we find warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals if not men, on reaching one degree northward of latitude 82.”

The Hollow Earth theory was not new. All the way back in 1692, English astronomer Edmond Halley, he of Halley’s Comet fame, suggested that the Earth was hollow, consisting of a 500-mile thick shell, two inner concentric shells and an innermost core. It is unclear if Symmes, a frontier soldier and trader, would have known about Halley’s work at the time he came up with his idea.

Symmes was the first to suggest the open poles, though, which became known as “Symmes’ Holes” in Hollow Earth lore.

The theory was ridiculed but also had supporters

John Weld Peck, a Cincinnati attorney and future U.S. district judge, described Symmes’ idea as an “absurd, foolish theory” in his Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications article in 1909. Yet, Peck also allowed that Symmes was not a charlatan but an earnest man with an idea.

“Let us view it not as we would the work of an erudite, trained scientist; but let us remember it was the offspring of the brain of a frontier soldier,” Peck wrote.

Symmes moved to Newport, Kentucky, in 1819, then settled in Hamilton in 1824, and began lecturing about his ideas to local audiences around Cincinnati. His theory was widely met with ridicule, but he found a few believers.

Among his supporters was James McBride, a Hamilton politician who helped develop the laws and survey the land for the Miami and Erie Canal. McBride also served on the board of trustees for Miami University and owned a 6,000-volume library that was one of the largest in the West as well as a collection of antiquarian artifacts from the Mississippi Valley.

Since Symmes had never published his theory, McBride wrote up the information from his lectures and in 1826 published “Symmes’s Theory of Concentric Spheres; Demonstrating That the Earth Is Hollow, Habitable Within, and Widely Open About the Poles.”

A proposed expedition

While most intellectuals rejected his theory, Symmes’ humility, coupled with a patriotic push to prove Americans the equals of Europeans, persuaded even his detractors to support an expedition to explore the North.

He held a benefit for the expedition in 1824 at the Cincinnati Theater on Columbia Street (now Second Street) between Main and Sycamore, but no one would supply the funding.

Jeremiah N. Reynolds, a newspaper editor in Wilmington, Ohio, had a few quibbles about the finer points of Symmes’ theory, but he became a strong proponent for the expedition. He prodded Symmes to do a national lecture tour, but the two parted ways after a few years.

Symmes returned to Hamilton, where he died on May 28, 1829, and was buried in the Hamilton cemetery off Third Street. When most of the cemetery’s remains were moved to Greenwood Cemetery in 1848, Symmes’ body stayed where it had been buried.

Reynolds continued to drum up support on his own but abandoned Symmes’ Hollow Earth theories, proposing an expedition to the South Pole and the South Pacific. This finally got support from President John Quincy Adams, who wrote in his diary on Nov. 4, 1826:

“Mr. Reynolds is a man who has been lecturing about the country, in support of Captain John Cleves Symmes’s theory that the Earth is a hollow sphere, open at the poles – his lectures are said to have been well attended, and much approved as exhibitions of genius and of science – but the theory itself has been so much ridiculed, and is in truth so visionary, that Reynolds has now varied his purpose to the proposition of fitting out a voyage of circumnavigation to the Southern Ocean. … It will however have no support in Congress. That day will come, but not yet nor in my time. May it be my fortune, and my praise to accelerate its approach.”

It should be noted that Adams’ use of the word “visionary” at the time meant “imaginary,” and he only agreed to support the expedition once the Hollow Earth aspects were removed, according to Smithsonian Magazine. However, when Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, the project was dropped.

So, Reynolds and his partner took their own private expedition in 1829 to the South Pole “opening.” When the ships reached the Antarctic shore, they couldn’t cross the ice, so they turned back, only to have the crew mutiny and abandon them in Chile. (One of Reynolds’ writings from this trip, the account of Mocha Dick, the giant white sperm whale of the Pacific, inspired Herman Melville to write “Moby-Dick.”)

President Jackson changed his mind and renewed the expedition plan, approved by Congress in 1836, but without Reynolds. The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842 traveled throughout the Pacific Ocean, adding to the scientific knowledge with samples that helped to shore up the collection of the new Smithsonian Institute.

While the expedition had nothing to do with proving or disproving Symmes’ Hollow Earth theory, that had been the impetus for it.

Symmes’ ideas have become popular in fiction, inspiring stories by Edgar Allan Poe, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jules Verne.

Additional sources: “The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842” by William Stanton, Wikipedia, Enquirer and Cincinnati Post archives.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What is the Hollow Earth theory? Looking at its connection to Ohio