Alfred Kelley's Columbus mansion was 'The House That Saved Ohio,' but it couldn't be saved

It was called “Kelley’s Mansion” by some, and “Kelley’s Folly” by others. And it was probably a bit of both. In its time, the place Alfred Kelley called home in Columbus was second only to the new Statehouse as a grand example of Greek Revival architecture at its best in size, scale and detail.

The massive residence was a tribute to the drive and aspirations of one of the more remarkable men in the story of Columbus and Ohio. And the story of what became of it after his passing is a reflection of how we came to have historic preservation in Ohio's capital city.

But first, a bit about the man. Alfred Kelley was born in Connecticut in 1789 and was one of six sons of Daniel and Jemima Stow Kelley. The Kelleys had been in America since the 1600s, and were a family rather frequently on the move. The Kelleys raised their sons to be active in the search for new life in new lands.

One of the older Kelley boys, Datus Kelley, went west and soon found both opportunity and a new home in a small settlement mapped by one Moses Cleaveland. Cleaveland left the newly platted place and never came back. Perhaps with a little humor the place came to be called Cleveland in his wake.

Datus Kelley was attracted to the new village, and soon persuaded his brother Alfred to join him. Alfred Kelley came to Cleveland, worked hard, made friends and soon was elected the first mayor of Cleveland. In 1814, he left for the capital of Ohio, then in Chillicothe, to be a state representative.

Alfred Kelley liked the job. When the new Statehouse opened in the new town of Columbus, Kelley came to town and liked both the place and his place in it. In 1816, he married Mary Welles and traveled back and forth to Cleveland for several years.

In time, Kelley moved from the Ohio House to the Ohio Senate and was spending most of his time in Columbus. Mary Kelley convinced her husband that the family, eventually with 11 children, should move to Columbus.

Alfred Kelley agreed, and in 1830 bought 18 acres fronting on East Broad Street in what was then considered to be “way out in the country.” It was four blocks from the Statehouse. It also consisted of what some people today would call a “wetland.” People at the time called it a “swamp,” and no place to build a house.

But Alfred Kelley had a plan. He buried hundreds of feet of drainage tile and built a brick sewer to catch water and carry it to the springs to the north that fed the creek that gave Spring Street its name. With the land dried out, he began to build his dream house.

It was quite a house. Constructed of eastern Ohio grey sandstone, the building was 65 feet on a side and four stories tall. A main portico two stories high projected out from the front, and included a steep parapet above major columns with Doric capitals supporting the building. There were ten columns in all — each constructed from a single stone.

Presumed to have been designed by Kelley himself, the house was completed in 1838. It was second only to a newly proposed statehouse as being one of the best examples of classical revival architecture in America. While Kelley was building the great house – often called “Kelley’s Folly” by his opponents – Kelley was making his mark. He came to be remembered as the Father of Ohio’s Banking System and the Father of Ohio’s Canal System. When Ohio’s finances faltered in the economic depression of 1837, Kelley pledged his house as collateral to insure payment of the state’s debt. It came to be called “The House that Saved Ohio.”

Alfred Kelley died in 1859. His family lived in the great house until 1906. The house was then sold to the local Roman Catholic Diocese, which used it as the Cathedral School until 1963. Then new uses were proposed.

The diocese offered the house to anyone who could move it. An effort to raise $100,000 for the move failed, and in a last effort the house was photo documented as it was taken apart stone by stone. The stones were stored in Wolfe Park along Alum Creek for a time. In 1966, most of the stones were moved to the north part of the Ohio State Fairgrounds. In 1971, they were removed once again and taken to the Hale Farm site near Cleveland where Kelley had once been mayor. And there they stay.

The unsuccessful effort to save the house, which was replaced by the since-demolished Christopher Inn, convinced a number of people that it was time to organize for historic preservation in Columbus.

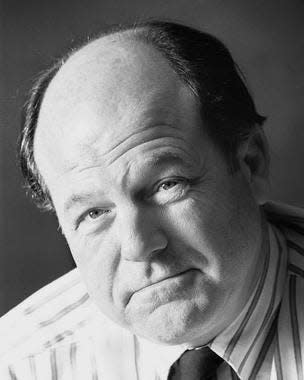

Ed Lentz is a local historian and author who writes this weekly "As It Were" column for The Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Alfred Kelley's mansion became known as 'The House That Saved Ohio'